Saturday, 29 September 2018

On demand: "Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story"

Bombshell outlines both an especially stellar example of Hollywood underestimating one of its talents, and a woman's story nobody had previously cared to tell in any detail. In Tinseltown circles, Hedy Lamarr was regarded as a looker, not a thinker: the unabashed European import who had gambolled naked through 1933's Extase, so-called "armpiece" of a Nazi arms manufacturer back in her native Hungary, seized upon as tempting new eye candy (and one of the visual inspirations for Disney's Snow White) after she crossed the Atlantic at the behest of Louis B. Mayer in the late Thirties. There was, however, more going on than met the eye and camera lens. By day, Lamarr shone and sparkled, often in MGM vehicles unworthy of her; by night, she tinkered, designed, invented, swapping the sound stage for the drawing board. She drew up planes with Howard Hughes, took a crack at creating dispersible cola cubes for overseas combatants, and - as WW2 geared up - hit upon a breakthrough in frequency disguise that turned several key battles in the Allies' favour, and led, by hook or by crook, to today's WiFi technology. That's right, the performer who made Bob Hope's eyes pop out on stalks in 1951's My Favorite Spy was more than partially responsible for you reading this review online today. It can't help but make you wonder: is Blake Lively somehow key to getting those easy-travel jetpacks we were all promised? Does Gemma Arterton have a time machine in her shed?

The triumph of Alexandra Dean's documentary lies in how it pulls together the various strands of Lamarr's story - rounding up those descendants and journalists who knew only one or two sides of this multifaceted figure - and, in so doing, comes to write the extraordinary biography that its subject, an adventuress who withdrew from the world in later life, was never able to complete for herself. It's a pageturner of a movie: pacy, not short on gossip (according to Lamarr, Hughes was the worst lover she ever had), and self-evidently relishing the challenge of telling a big, broad, hitherto generally undertold story - the kind of legend Old Hollywood generated with staggering regularity - within a TV-friendly 90 minutes. Dean has full access to the Lamarr archive - the letters, tapes and impossibly glamorous headshots - but crucially foregrounds the blueprints and notebooks at the expense of the film clips: one look at Lamarr browned up with boot polish as the sashaying island girl "Tondelayo" in 1942's White Cargo is all we need to see how the movies repeatedly insulted this performer's considerable intelligence. Though there are elements specific to this particular moment in world history - the same bosses who screwed her out of the frequency-hopping patent sent her out to sell kisses for War Bonds - Bombshell turns out to be telling what now presents as a familiar story: that of a creative - a creator - who found herself at the mercy of a male-owned and operated system.

It is, in many ways, a very modern arc: after being introduced to her as cheesecake, the movies failed to take Lamarr seriously, then kicked her to the kerb once the looks that made her such a hot property in the first place began to fade. Not for Hedy the camp revivals of Bette, Joan or Zsa Zsa; instead, she beat a Garbo-like retreat after botched cosmetic surgery, intended to regain a measure of that teenage skinnydipper's allure. (Dean notes that Lamarr was even something of an innovator in this field, instructing the surgeons where to nip and tuck, but painful-to-watch footage of the actress in middle age suggests the results were less than entirely successful.) The injustice the film frames - and corrects - elevates it over those rather more superficial celebrity profiles that now land in our cinemas every other week; by contrast, Dean appears genuinely fascinated by the insides of things, whether training her camera on music boxes and player pianos, or considering her singular subject's headspace as she suffered through a series of disappointing relationships with men who fell for the image and offered no match for her smarts. Dean is the first director in cinema history to think about Hedy Lamarr in ways that go beyond skin deep, which is why her film, as much textbook as it is memoir, forms both an education and a polite request: to look closer, listen to women, and ask red carpet interviewees not what they're wearing, but what they're working on. Blake and Gemma: the moment is yours.

Bombshell is available to stream via the BBC iPlayer for the next month.

Friday, 28 September 2018

For what it's worth...

Top Ten Films at the UK Box Office

for the weekend of September 21-23, 2018:

1 (new) The House with the Clock in its Walls (12A)

2 (new) A Simple Favour (15)

3 (3) Crazy Rich Asians (12A) **

4 (4) King of Thieves (15)

5 (2) The Nun (15)

6 (new) Mile 22 (18)

7 (1) The Predator (15)

8 (5) Christopher Robin (PG) **

9 (8) Incredibles 2 (PG) ****

10 (6) Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (PG)

(source: theguardian.com)

My top five:

1. The Godfather

2. The Captain

3. Lucky

4. American Animals

5. Anchor and Hope

Top Ten DVD sales:

1 (new) Deadpool 2 (15) **

2 (1) Avengers: Infinity War (12) ***

3 (2) The Greatest Showman (PG)

4 (new) Escape Plan 2 (15) *

5 (new) Deadpool: Double Pack (15) **

6 (3) Peter Rabbit (PG)

7 (4) Rampage (12)

8 (6) The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (12)

9 (new) Supergirl: The Complete Third Season (12)

10 (new) Life of the Party (12)

(source: officialcharts.com)

My top five:

1. Custody

2. Solo: a Star Wars Story

3. Apostasy

4. Mary and the Witch's Flower

5. Avengers: Infinity War

Top five films on terrestrial TV this week:

1. King Kong [above] (Saturday, five, 2.30pm)

2. Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (Sunday, five, 6.50pm)

3. Blades of Glory (Tuesday, BBC1, 11.45pm)

4. Hellboy II: The Golden Army (Saturday, ITV, 11.30pm)

5. Bend It Like Beckham (Sunday, C4, 1.25pm)

2. Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (Sunday, five, 6.50pm)

3. Blades of Glory (Tuesday, BBC1, 11.45pm)

4. Hellboy II: The Golden Army (Saturday, ITV, 11.30pm)

5. Bend It Like Beckham (Sunday, C4, 1.25pm)

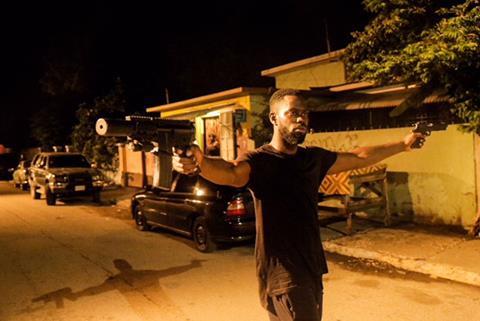

"Redcon-1" (Guardian 28/09/18)

Redcon-1 **

Dir:

Chee Keong Cheung. With: Oris Erhuero, Carlos Gallardo, Mark Strange, Katarina

Leigh Waters. 115 mins. Cert: 18

It’s

been sixteen years since Danny Boyle’s 28

Days Later… and just over a decade since its sequel – which is to say a

fair while has passed since a homegrown zombie movie scaled up to theatrical

proportions rather than shuffling towards video on demand. (Your reviewer

retains a soft spot for 2012’s Cockneys vs. Zombies, with its irresistible combination of Richard Briers,

anti-gentrification wisdom and Chas Hodges theme tune, but that was always

bound for regular post-pub rotation on the Horror Channel.) This legitimately

widescreen indie endeavour – in which emerging tyro Chee Keong Cheung curates

apocalyptic visions of Albion on interesting Rochdale and Glasgow locations –

is finally undermined by rookie errors, but otherwise takes a half-decent shot

at using its modest budget to fill that gap.

If

anything, Cheung displays that fanboyish tendency to give the audience more

than they might actually need. He opens with a jolting barrage of hyper-grim

imagery grabbed from anywhere and everywhere; his attack scenes pile on

splatter and ear-splitting howls in a manner that leaves Boyle, generally

regarded as the Zebedee of modern cinema, looking subdued. Such out-of-the-gate

enthusiasm is infectious to some degree, but the appealing cleanliness of the

initial narrative line – multiracial Special Forces are gradually picked off

while retrieving a cure-touting doctor from a biohazard zone – is soon

compromised by switchback after switchback.

It peaks too soon: after the relentless, jugular-targeting confrontations of its first hour, some of its invention and force can be felt bleeding out over the long-seeming second. Yet this director is still capable of reaching deep into his spacious if sometimes ungainly tombola of tropes and pulling out a funny, bleak, original image. Amid an appreciable cross-section of the undead (S&M zombies! Community Support zombies!), I particularly enjoyed the zombie postie, found mid-round, rabidly tossing letters into long-abandoned gardens. (We’ve all known mail workers like that.) Cheung shows promise as a shotmaker and stager of blunt-force action; if somebody cares to arm him with a script editor and production grants, we could have a discovery of sorts on our hands.

Redcon-1 opens in selected cinemas from today.

Wednesday, 26 September 2018

Breaking waters: "Anchor and Hope"

There are several reasons to feel fondly towards the disarming indie Anchor and Hope, shot around London by the Spanish writer-director Carlos Marques-Marcet. It's one of very few films to make attractive use of the capital's canal system (and, in an eccentrically novel touch, to linger on those canals' uterine properties: you'll never look at lock gates in quite the same way again). It's one of those multilingual co-productions - completed with EU funding - which will likely disappear after next March; its worldliness would seem more than ever an endangered species as we enter the era of Downton movies and Johnny English sequels. And there's a breezy warmth coming off the screen, with which you could fool yourself the British summertime isn't over yet. All this has to be set against the fact that, for at least an hour, what we're getting is really no more than a sitcom crammed into a barge moored somewhere around Gasholder Park - a sort of Man About the Houseboat. Having put down roots of a kind, butch, impulsive Kat (Natalia Tena) and sensitive femme Eva (Oona Chaplin) are floating ideas for the next stage of their relationship. Eva wants kids; Kat does not. A potential solution to this impasse arrives in the form of Kat's aptly named Spanish pal Roger (Euro cinema's shaggiest new pin-up David Verdaguer, the dad in Summer 93), who presents as a willing sperm donor to just about every woman he meets. Thereafter, it's a matter of these characters rearranging themselves within some especially narrow confines, although the script - written by Marques-Marcet and Jules Nurrish - throws in one second-hour curveball that really does rock the boat.

It's very clearly the work of a close-knit cast and crew messing around by the river: Chaplin's mother Geraldine is roped in for two scenes as a former flower child bearing cautionary tales from the counterculture and lecturing these kids on the limitations of alternative lifestyles (rather pointedly, the character goes under the name of Germaine), and matters proceed in extended, sometimes rambly semi-improvised scenes in which the central trio thrash out the finer points of their futures together. (A real sitcom would have a script editor aboard to pare back the indulgence, and hone the dialogue to its funny essence.) Still, it should work so long as you're prepared to travel alongside these goofy, charming performers, whose gameness - their willingness to go with the ebb and flow of any given development - fits the characters to a T; this being the case, you'll happily follow everyone into the more dramatic second half, wherein it suddenly becomes apparent there are stakes (and hearts, and lives) in play. Its ultimate destiny may be to serve as a watermark in academic studies of how film and television have responded to the rise of non-traditional family units: you can't miss how relaxed the film is around its own set-up. In any previous decade, sperm donation and same-sex parenting would have served as the basis for farcical conniptions or deeply conservative horror stories. Here, they're just developments people muddle through, figure out, get on with. Its relative ordinariness - the calm and steady hand Marques-Marcet keeps on the tiller - is a big part of its appeal.

Anchor and Hope opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Sunday, 23 September 2018

For what it's worth...

Top Ten Films at the UK Box Office

for the weekend of September 14-16, 2018:

1 (new) The Predator (15)

2 (1) The Nun (15)

3 (new) Crazy Rich Asians (12A) **

4 (new) King of Thieves (15)

5 (2) Christopher Robin (PG) **

6 (4) Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (PG)

7 (3) BlacKKKlansman (15) ****

8 (6) Incredibles 2 (PG) ****

9 (8) Hotel Transylvania 3: A Monster Vacation (U)

10 (5) The Meg (12A) ***

(source: theguardian.com)

My top five:

1. The Godfather [above]

2. The Captain

3. Lucky

4. American Animals

5. Faces Places

Top Ten DVD sales:

1 (1) Avengers: Infinity War (12) ***

2 (2) The Greatest Showman (PG)

3 (5) Peter Rabbit (PG)

4 (3) Rampage (12)

5 (new) Spitfire (PG) ***

6 (4) The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (12)

7 (new) I Feel Pretty (12)

8 (new) The Krays: Dead Man Walking (18)

9 (7) Ready Player One (12) ***

10 (11) Black Panther (12) **

(source: officialcharts.com)

My top five:

1. Custody

2. A Quiet Place

3. Avengers: Infinity War

4. The Rape of Recy Taylor

5. Ghost Stories

Top five films on terrestrial TV this week:

1. King Kong (Sunday, five, 6.30pm)

2. Silver Linings Playbook (Wednesday, C4, 1am)

3. The Guest (Friday, C4, 12.40am)

4. Paranorman (Sunday, C4, 1.25pm)

5. Along Came Polly (Sunday, five, 4.50pm)

2. Silver Linings Playbook (Wednesday, C4, 1am)

3. The Guest (Friday, C4, 12.40am)

4. Paranorman (Sunday, C4, 1.25pm)

5. Along Came Polly (Sunday, five, 4.50pm)

Triumph of the Will: "The Captain"

After racking up a couple of flashy box-office hits (2002's Tattoo, 2003's The Family Jewels), director Robert Schwentke left Germany around the point its filmmakers began making renewed efforts to address the country's troubled history. While his contemporaries made Downfall and The Lives of Others, Schwentke would be in Hollywood, making a fitful (albeit doubtless well-compensated) career churning out passing multiplex filler, films like 2005's Flightplan, the 2009 adaptation of The Time Traveller's Wife and 2010's RED. With that chapter at an end - perhaps as a result of the eternally underwhelmed responses to his YA Divergent films - the filmmaker has returned home to write and direct the kind of film the German industry might have encouraged him to make had he stayed put in the century's first years - only now he gets to make it with an extra decade's worth of showmanship and storytelling nous under his belt. The results qualify as the biggest surprise of the week.

Shot in wintry black-and-white (with thematically helpful shades of grey in between), The Captain recounts the remarkable and instructive true tale of Willi Herold (Max Hubacher), a deserter from the German army who, during his flight from the frontlines of WW2, had the weird fortune to stumble across a jeep containing an errant Nazi officer's uniform and papers. Assuming this new identity gave a man fleeing in fear of his life food, board, good standing with those he subsequently encountered, and even a small army of loyal followers to fight battles of his own devising; as these developments played out on screen, I was reminded of that very early episode of It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, where the gang reluctantly agree to burn the same, inherited items of clothing ("It just seems like a waste of a perfectly good Nazi uniform") after they spur on certain individuals to commit terrible abuses of power. Schwentke's film, however, sets out its stall as tragedy with an early graphic that establishes Herold made his discovery mere weeks before the end of the war. Whatever superpowers this outfit bestowed upon him, they would very quickly wear off; yet this didn't stop Willi Herold leaving a jawdropping trail of destruction in his wake.

The question hovering over at least the first act's events is: well, what would you do? What looks like opportunism from one perspective might look from another like social mobility in a country gone to naught. The complicating kicker is that said mobility demanded Herold act in a manner concordant with the uniform, first by shooting those unlucky enough to have been found guilty of the same looting he himself had got away with, then by accepting an offer to become onsite efficiency expert for an overstretched yet hitherto comparably peaceful concentration camp. At each critical juncture, the camera finds in Hubacher a boyish malleability, a willingness to do anything to be accepted - and not necessarily from a desperate need to stay alive. Instead, this Willi Herold's eyes grow darkly dreamy with the prospect of reentering the military at a far higher level than the one he exited at, with all the benefits (respect of and power over men, an extra glass of red at lunch, the attention of women) and only a little of the dirty work. More chillingly yet, his deception spreads: he demonstrates how easy an imposture like this is to carry off, and his entourage, themselves waiting for a chance to push their luck or otherwise go off-book, laps it up.

If The Captain shapes up as a good deal more than just another black-and-white period piece, it's because Schwentke's script taps into a deep well of psychology, still recognisable today in the clique, the committee, the corporation: one bad apple, and the entire fruit basket can start to fester. It's just that the cover-up here, outlined in a grisly sequence around the halfway mark, involves bodies in a pit. Needless to say, there is a seriousness about this undertaking that wasn't readily apparent in, say, Flightplan. The second half digs in and doubles down on the consequences of Herold's actions, coming back up with a steady parade of horrors: mass executions, bodies blown to bits, a Salò-like retreat to a hotel, a forest overrun with skeletons. (That monochrome begins to resemble Schindler's List far less than it does Night of the Living Dead: one man gets bitten by the power bug, and soon everybody around him is infected.) They're kept from exploitation, however, by Schwentke's clear-eyed deconstruction of fascism as equal parts madness, virus, self-interest and shared delusion, a game that may start with dressing-up or role play, but which soon drags everybody south, if not underground, for real. The astonishingly bold closing images - too close to home to be as crass as they might have been, a coup de cinéma perhaps only someone who's worked in Hollywood would think to attempt - confirm The Captain as a film that speaks as unnervingly to 2018 as it does to 1945.

The Captain is now playing in selected cinemas.

Rolling: "Faces Places"

Important to get out of the house when you're in your eighties. Faces Places forms the latest extension of that wanderlust cinema the director Agnès Varda has pursued ever since she veered off the beaten track of fiction into more essayistic territory some decades back, a film that carries us into the French provinces with the intention of meeting new people, sharing new ideas, and exploring those regions where art and life interact. She's found herself a fellow traveller this time: JR, thirtysomething whizzkid of French photography, whose self-image (pork pie hat, ever-present sunglasses that set his companion to thinking of Jean-Luc Godard) has been cultivated almost as carefully as Varda's Madame Pepperpot look. Put them together, as Faces Places does, and they could be a French Fred and Ginger: he gives her fresh eyes (and we learn her ocular health is not as it was), she gives him wisdom. They've been united by a shared desire to make art of the people for the people, and so we join them hitting the road as part of JR's Inside Out project, touring the backroads of France in a mobile camera truck, taking photographs of the locals that are then converted into huge billposters and pasted to the sides of homes and buildings. So: two artists at the wheel, a truck running on gas and toner, a populace awaiting their close-up. On y va.

The first surprise for British viewers will come from encountering a subtitled movie that so closely resembles an episode of Changing Rooms or DIY SOS in its form. Varda and JR freewheel into town after town, set about transforming the immediate eyeline, then present the results to those who live and work thereabouts. The last remaining tenant in a row of miners' cottages is moved to tears by the permanence this taskforce's art affords her; a farmer stands quietly proud upon seeing his image elevated to a scale usually reserved for A-listers on movie billboards; an abandoned housing estate is filled with life the authorities could never provide. Almost inevitably, Varda is drawn towards her beaches, and to the faces and places of her past, although one of the film's pleasures lies in the realisation that this pint-sized grandmother has become such a national treasure that everyone who falls within her orbit - the hip young JR, a passing gendarme, grizzled blue-collar types who might once have entertained the thought of voting Le Pen - feels obliged to defer to even her more fanciful creative requests. (Having Varda show up in one's hometown to take photos of your nearest and dearest must be like having Judi Dench pop into your community theatre to ask whether or not she could road-test a sonnet or two.)

The steady gathering of portraits - and the assiduous search for the exact right frame: fish on water tanks, dockers' wives on cargo containers - allows Faces Places to develop into a portrait in itself: here is rural France as it is/was at the very beginning of l'ère macronienne. Like the huge portraits that roll out of a slit in the side of JR's van, the film covers a lot of ground. While our creative prime movers are waiting for their photos to develop and the paste to dry, Varda's curious camera scoots off to furnish us with generally diverting sidebars on such diverse subjects as bell-ringing (in both its churchy and Anita Ward senses), goat farming and salt production; we're offered both a terrific sight gag involving a postman, and some consideration of what it feels like to retire. (The suggestion has been made that this will be Varda's final (ad)venture; when asked by JR why she's unafraid of death, her response is transcendentally simple: "Because that'll be that.") You're reminded that Varda's great triumph has been the sheer amount of life - her own life, and the lives of others - she's kneaded into her art; where her fellow New Wavers spent their careers becoming the kind of standalone (in some cases standoffish) figures they once extolled in prose, a collaborative exercise such as the one documented here - shot with JR, reliant on the willing participation of the people - begs reading as a crafty democratisation of the auteur theory, undertaken not by some great man, rather a four-foot-five inch woman.

There is, however, one subject who eludes Varda, not through any failing of her own. Late on, the travelling twosome head to Switzerland for a planned meeting with Godard; the only trouble is that Godard fails to show at the allotted place, leaving behind only a cryptic message for his pursuers. The snub is not untypical - Godard appeared only via videophone at this year's Cannes - but you can see how it hurts Varda, especially after she's paid such fond homage to the Louvre sequence in Bande à part. As the filmmakers rock up outside Godard's shuttered, apparently vacated house, it is as if an old friend no longer wants to come out and play. (Two especially poignant details from this sequence: JR vainly shouting "Jean-Luc?" at an upstairs window, and Varda tying the bag of brioche she's brought to the front door even after bursting into tears.) The inclusion of this unhappy non-rendezvous serves to set up a contrast between two strains of personality-driven art, one outgoing and open-minded, the other solitudinous and sententious, keener to impose itself than initiate any dialogue, far less interested in anything so trivial as people. (Is this just how men get with age?) In the next few years, film historians will have to weigh up both careers, both lives, and accept that both Godard and Varda did much to change our understanding of the cinema - but I think if you had to pick only one to spend any considerable length of time with, the choice would now be very easy. She's the one bringing pastries.

Faces Places is now showing in selected cinemas, and is available to stream via Curzon Home Cinema.

Saturday, 22 September 2018

The limits of control: "Never Here"

To start out on a positive note: it's encouraging to know that our increasingly commercialised release schedules can still find room (albeit on just the one UK screen) for a leftfield oddity like Never Here, a notional thriller from writer-director Camille Thoman set on the spookier fringes of the Manhattan art scene. In a marketplace where audiences turned a collective nose up at the AI-enhanced killing machine of last month's Upgrade, Thoman's film is almost certainly doomed from a commercial perspective, but it's reassuring to think someone thought it worth taking a chance on. Mireille Enos (from the US redo of TV's The Killing) plays Miranda Fall, a Sophie Calle-like conceptual artist introduced at the opening of her new, acclaimed show, themed around the contents of a stranger's phone that she found lying in the street. Her own security comes under review after she and mentor-lover Paul (Sam Shepard, typically classy in his final screen appearance) witness a woman being attacked outside her apartment one night. The police prove no help whatsoever in tracing the assailant; Miranda's own investigations reveal only the limits of her creative control - and, alas, Thoman's limits, too. I say notional thriller, because the film displays the glacial-to-listless pacing and terminally off-kilter framing of shrug-worthy video art.

Everything put before us is slightly, deliberately off. Enos's unnerving smile, simultaneously pained and spaced out, is that of a woman coming around from extensive dental surgery; the supporting cast drift in and out of these sets in disconcerting ways; and Thoman puts weird emphases on props, signs and lines of dialogue, casting out so many red herrings that they start to obscure what she's actually getting at. Very soon, Never Here assumes the look of a failed experiment, the work of a filmmaker entering a new medium (Thoman comes from theatre) and determining to use every effect available to her over two hours of cinema. Artless zooms predominate, as do scenes that find the camera creeping up on the central character from various angles to doubly, triply, quadruply underline a point - this woman feels somebody's watching her - that has long been understood. (There's about 20-25 minutes' footage of the Enos nape, which even admirers would surely concede is too much.) It's a minor problem that the film never manages to escape its comfortably appointed boho bubble - that it is, in the end, very much a film about a celebrity artist who, in the middle of a loft renovation, comes to worry that someone's moved her chaise longue. It's a much bigger one that it should inhabit this space in such a heavyhanded, dully unengaging manner, without a trace of Calle's wit or playfulness.

Never Here is now playing at London's Prince Charles Cinema.

Friday, 21 September 2018

"The Intent 2: The Come Up" (Guardian 21/09/18)

The

Intent 2: The Come Up **

Dirs: Femi Oyeniran, Nicky “Slimting” Walker. With: Ghetts,

Ashley Chin, Femi Oyeniran, Nicky “Slimting” Walker. 103 mins. Cert: 15

For those who missed it, 2016’s The Intent was a late, independently produced entry in the cycle of

inner-city British crime dramas; its rough, grime-infused edges differentiated

it from Noel Clarke’s upwardly mobile ‘Hood

series, but made for an unintentionally gruelling watch. Money has now been

found for a prequel, which proves a touch more polished – an offscreen

partnership with Island Records carries the first film’s stick-up crew to

Jamaica – yet suffers from the same underlying flaws. Writer-performers Femi

Oyeniran and Nicky “Slimting” Walker are simply far more interested in filming

themselves wielding shotguns in fetishizing slo-mo than they are in putting in

the hard yards of character, or telling a coherent story.

For a long time, there’s evident confusion as to what film The Come Up intends to be. After a nostalgic

prologue, where a This is England-style

houseparty is rudely interrupted by a pistol-packing child, it shifts into a

promising prison stretch, before springing its two thousand characters – a role

for every last member of the directors’ entourage – with a few clumsy lines of

exposition, and EasyJetting them all into Kingston for an even cheaper The Harder They Come. For all Chris

Blackwell’s largesse, the budget never seems big enough to stretch in any one

direction: hence the early pursuit conveyed chiefly by asking the performers in

one car to look very intently into the rear-view mirror and describe the unseen

vehicle behind.

Less woebegone elements include superior location work, cinematographer Tom Watts giving even a passing nocturnal insert of a Costcutter a vaguely Hopper-ish allure; Adam Deacon, displaying newfound assurance as the junior crimeboss tailing our antiheroes; and Sharon Duncan-Brewster, commendably no-nonsense in running an empire from the back of a beauty salon. Time and again, though, a near-fatal combination of creative ADHD and directorial ego yanks us away from these strengths and back towards these films’ dunderheaded raison d’être: giving posturing musicians-not-quite-turned-actors the chance to engage in generally indifferent gunplay. If diptych begets triptych, the ratio of swagger to basic competency will need addressing.

The Intent 2: The Come Up opens in selected cinemas today.

Thursday, 20 September 2018

Hard-knock life: "A Northern Soul"

The British documentarist Sean McAllister first seized cinephile attention with 2015's A Syrian Love Story, which brought a sometimes distant-seeming conflict into sharp, stark, emotionally potent focus by following one relationship over several years. McAllister's follow-up A Northern Soul is a homecoming of sorts, returning the filmmaker to his native Hull at an interesting moment: early 2017, when the European City of Culture celebrations were first gearing up (McAllister served as artistic director for the spectacular opening ceremony), the diffuse cloud of Brexit was looming large (Hull voted 68-32 to leave the EU), and a half-decade of Tory austerity cuts were beginning to bite hard. Again, he finds the personal in the political (and vice versa) by tagging along in the wake of a friend: Steve Arnott, a fortysomething warehouse operative, young Mark E. Smith lookalike and rap enthusiast, whose contribution to the city's artistic beanfeast was to tour schools with the Beats Bus, a mobile recording van in which local children could lay down beats and rhymes of their own. While he does the rounds with that project, McAllister very precisely pins down the finer details of where Steve is in life: living with his mum after the collapse of his marriage, stuck with nine thousand pounds' worth of payday loan debts, a ninety-minute drive away from the daughter he dotes upon. Still, he soldiers on; he gives back. Only rarely does McAllister find him complaining about his lot - though it does seem a lot.

The film born of this careful, intimate portrait turns out to be two documentaries in one, and it's a testament to McAllister's editorial skill that he finds the right balance between them at any given point in Steve's progress. The more conventional of these two films - what we might call the poptimists' film - takes in the joy that follows whenever Steve sets foot inside a classroom and begins breaking the basics of rap down for the benefit of visibly enthused youngsters; his tutelage transforms the shy into camera-hogging, mike-dropping MCs, habitual stutterers into bolshy wordsmiths, troublemakers into artists. (A point is subtly made: here is the kind of elevating arts education our current administrators are quietly defunding and dropping from the curriculum.) There might well have been a straightforward commercial hit in that movie, yet McAllister also wants to show us something more: the hard graft of everything else in Steve Arnott's life. It's the 4:40am starts on cold winter days; the pressure that comes from trying to combine this volunteer work with a full-time paying gig; the stark reality of being forty years old and having no kind of job or life security whatsoever. Every now and again, the two films merge. In the aftermath of a public performance, we find one child in tears because his dad couldn't get time off work to see him. (Again, it's not dwelt on, but there may be something telling in the fact the kids are performing a post-Hamilton number about the city's links to slavery.)

McAllister's theme, it transpires, is men at the mercy of a system that permits very little other than work; he has returned to this City of Culture to illustrate just how hard it is nowadays for anyone to be cultured, creative, or more than a cog in a machine. The most damning development comes halfway through, when the employer that provided Steve with the Beats Bus hauls him in for a performance review that rules he's been spending too much time away from the workplace, and promptly removes him of his hard-earned bonuses; mulling this decision over a pint, Steve declares - with typical practicality, and some of the language that made the film's original certificate a bone of contention - "Fuck being a starving artist." At 70 minutes, it feels brief, especially when set against its epic-seeming predecessor (itself only 76 minutes; McAllister makes his points with admirable economy): I couldn't help but wonder how Steve voted (if he voted) back in May 2016, although we must concede not everything has to be about Brexit, and that such information may have altered viewer perceptions one way or another. (As it is, A Northern Soul sets itself up nicely for a sequel: where will this man, this community, this country be in two years' time?) There's a forceful honesty, however, to the way McAllister's camera keeps rolling after school, to witness Steve collapsing on his mother's sofa - partly from exhaustion, partly in despair - and wondering, as many have, why on earth he's bothering. Anyone fool enough to doubt the generosity or work ethic of the people of the North, look sharpish.

A Northern Soul is now showing in selected cinemas.

Tuesday, 18 September 2018

On demand: "The Intent"

2016's The Intent has stood for a while as the last, sobering spin in that low-budget British hood cycle initiated by Noel Clarke: the target audience may well have grown up, the industry has veered off in pursuit of exportable Downtoniana, and most sentient adults have agreed that fetishised knife and gunplay probably isn't the healthiest thing for filmmakers to be putting out onto the streets. Its rougher edges initially make it a more intriguing proposition than Clarke's polished, upwardly mobile product (some of which, lest we forget, was sponsored by Costa Coffee). Directors Femi Oyeniran and Kalvadour Peterson recruit non-professional actors (many of whom hail from grime music) and foster a semi-improved performance style, heavy on a street slang the Netflix subtitlers prove almost wholly incapable of handling. There's an underlying bathos, however, in the fact the narrative should rest so heavily on a matter of nominative determinism: introduced cradling a pistol as a child, our narrator Gunz (Dylan Duffus, discovered in Penny Woolcock's One Mile Away) finds himself caught between loyalty to his South London stick-up brethren and doing the right thing for the wider community. (He would presumably have found life that much easier if he'd adopted the street name Sconez or Daisiez.)

There's less of that slumming imposture written through the comparable Clarke films - little sense of RADA-trained actors acting street so as to make off with already deprived viewers' pocket money - but these rough edges often stray into rank amateurism. The Intent is impossibly slack and unfocused in its plotting, and vague around even its central characters: a major revelation about Gunz at the half-hour mark is all but forgotten about for the rest of the movie, as Oyeniran and Peterson switch their attention to shooting montages of dirty money changing hands, and images of what that money can buy a man - flash motors, sex in nightclub toilets, lots of lovely drugs, and lapdancers to snort those drugs off. (Men account for something close to 95% of the credited roles, which possibly explains the bellendrical division of the film's female characters into nags and slags.) There's clearly still cash aplenty in these ghetto entertainments, but increasingly, they've come to seem like a creative dead end, a last, desperate resort for aspirant filmmakers and viewers alike: Clarke blew a lot of energy and much of his industry goodwill on the subgenre, BAFTA Rising Star winner Adam Deacon briefly lost his mind fighting its battles. All involved here clearly think it's an avenue worth pursuing - a prequel opens in the UK this weekend - but they might do well to heed the one genuine nugget of wisdom lost in the fog of their own script: "Don't be so busy making a living that you forget to make a life."

The Intent is now streaming on Netflix; The Intent 2: The Come Up opens in cinemas nationwide this Friday.

Sunday, 16 September 2018

Money talks: "Crazy Rich Asians"

Film historians addressing this century's turbulent first quarter will have to set aside whole chapters for two tectonic industry shifts: the move towards streaming as a preferred viewing option, and the growth of the Chinese film industry, developments that have increased levels of handwringing in Hollywood boardrooms by several hundred percent. 2018 will be the first year when total revenue at the Chinese box office surpasses total revenue in the United States - the reason why so many recent blockbusters have looked East for their actors (Bingbing Li in Transformers 4, Bingbing Fan in X-Men 7, Sung Kang in Fast & Furious 6) and monsters (Godzilla, the kaiju of Pacific Rim, the aliens behind The Great Wall), and why even a barely successful, dimly remembered piece of junk like 2013's Escape Plan earned a sequel by relocating its one willing cast member to Shanghai. A little further up the movie food chain, we find this week's Crazy Rich Asians, Warner Bros.' attempt to catch the eye and loosen the pockets of a gilded diaspora audience by adapting Kevin Kwan's bestseller with the aid of a predominantly Asian cast. Jon M. Chu's film opens with a Napoleon quote - "Let China sleep, for when she awakens, she will shake the world" - which presumably resonated with the suits who troubled to read the script; it goes on to demonstrate that while China may well have woken up and come online as a source of income, those films targeting her remain quite some distance behind the curve.

The Meg, Warners' midsummer toe-dip in similar international waters, was such a Nineties throwback it hired the man behind Cool Runnings and While You Were Sleeping to oversee its amusing yet bloodless man-versus-shark activity. (The strictures of censorship in Asia mean Western productions aiming offshore will likely come bearing those 12A ratings that flag how the commercial cinema has willingly defanged itself, for varying levels of profit, over the past two decades.) CRA is, for its part, a homage to those bright-and-breezy nuptial romcoms that were a matter of standard back when Sandra Bullock and Meg Ryan were in the ascendant, but which were brutally stomped all over by the likes of Matthew McConaughey and Gerard Butler in the years following the millennium, and now exist mostly on Netflix life support. You could cheer the fact that the prospect of easy overseas money has changed an industry paradigm - that a genre recently exiled to streaming platforms has been returned to our megaplexes - or note with regret that, creatively at least, the clock has been set back twenty years. More suited for discussion on the business than the arts pages, Crazy Rich Asians is another of this year's cinematic phenomena - not unlike Black Panther, that smashy-crashy-bang-bang movie successfully marketed as a revolutionary text - spun from the blandest of corporate fluff, a semi-expensive non-event movie with a script as dull as a press release, describing a wedding that may as well be a banking merger for all the legitimate romance and gaiety it conjures up.

From first smeary digital frame to last, it is recognisably the handiwork of Chu, a company man whose filmography - from his Step Up sequels to the Justin Bieber documentary - has rarely been troubled by depth or drama. Chu overlights every set-up, trowels on his soundtrack (Mandarin and Cantonese variants of familiar English-language hits, up to and including an icky last-reel cover of Coldplay's "Yellow") and seems at his happiest gathering shots of his wooden male leads' torsos, or constructing montages of food being prepared, positioning CRA as a popcorn Tampopo or Eat Drink Man Woman. Set it against the wisdoms of either of those films, and the whole thing looks doubly banal. After a dead-loss first act, set in place solely to get New York-based academic Rachel (Constance Wu) to a high-society wedding in Singapore, the film briefly crackles into life during a sequence that gathers funny people (Wu, Ken Jeong, Awkwafina) around the one dinner table, before defaulting to stock wedding-movie scenarios in which we're supposed to be swayed and seduced by the number of costume changes or flash cars on screen or the tallness of a hotel rather than anything being enacted. In terms of the com in its romcom, the film's meek, overpopulated soap opera leaves CRA light years behind a show like Fresh Off the Boat, the Disney-produced sitcom centred on a Chinese-American family in Florida.

That show - a ratings-winner on ABC in the US, somewhat brusquely treated by 5USA in the UK - has spent four seasons being sublimely goofy, satirical, provocative and weird, and allowing Wu, playing the clan's hard-nosed mother, to display just about the best timing in the world right now. Here, she's limited to playing relatable - Rachel's an academic, ergo the one person on screen who isn't crazy rich - and waiting for her Mr. Right to take a knee. (Modern American movies have a habit of wronging TV's better players: Steve Carell's big-screen career only really took hold after he started turning down all those insipid nice-guy roles he was stuck with after The Office finished, and it still pains this viewer to see Parks & Rec's adorable clown Chris Pratt being cast as bestubbled lunks.) FOTB may be one of those lightning-in-a-bottle triumphs pop culture occasionally generates, but it's also a demonstration of how creatives can do the necessary work of representation and so much else besides. CRA, by contrast, has the look of another recent American movie doing the least possible amount of heavy lifting to get its hands on a lot of money: hiring a director with no great vision to film a book that's already been a hit so as to give an audience that just wants to know what it's like to attend a fancy reception a mildly diverting, immediately forgettable time. It is very rich (and getting richer by the week, according to the box-office reports), and certainly doesn't shortchange us on the Asians front, but is only as crazy, funny or otherwise interesting as watching a business deal being brokered.

Crazy Rich Asians is now playing in cinemas nationwide.

Saturday, 15 September 2018

For what it's worth...

Top Ten Films at the UK Box Office

for the weekend of September 7-9, 2018:

1 (new) The Nun (15)

2 (1) Christopher Robin (PG) **

3 (3) BlacKKKlansman (15) ****

4 (2) Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (PG)

5 (4) The Meg (12A) ***

6 (6) Incredibles 2 (PG) ****

7 (5) Searching (12A) ***

8 (9) Hotel Transylvania 3: A Monster Vacation (U)

9 (8) The Equalizer 2 (15)

10 (new) Black 47 (15; Ireland only)

(source: theguardian.com)

My top five:

1. Lucky

2. American Animals

3. BlacKKKlansman

4. A Northern Soul

5. Wajib

Top Ten DVD sales:

1 (new) Avengers: Infinity War (12) ***

2 (3) The Greatest Showman (PG)

3 (2) Rampage (12)

4 (1) The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (12)

5 (4) Peter Rabbit (PG)

6 (new) Avengers: Triple Pack (12) **

7 (6) Ready Player One (12) ***

8 (new) Crisis on Earth-X (12)

9 (new) Arrow: The Complete Sixth Season (15)

10 (7) A Quiet Place (15) ****

(source: officialcharts.com)

My top five:

1. Custody

2. A Quiet Place

3. Avengers: Infinity War

4. The Rape of Recy Taylor

5. Ghost Stories

Top five films on terrestrial TV this week:

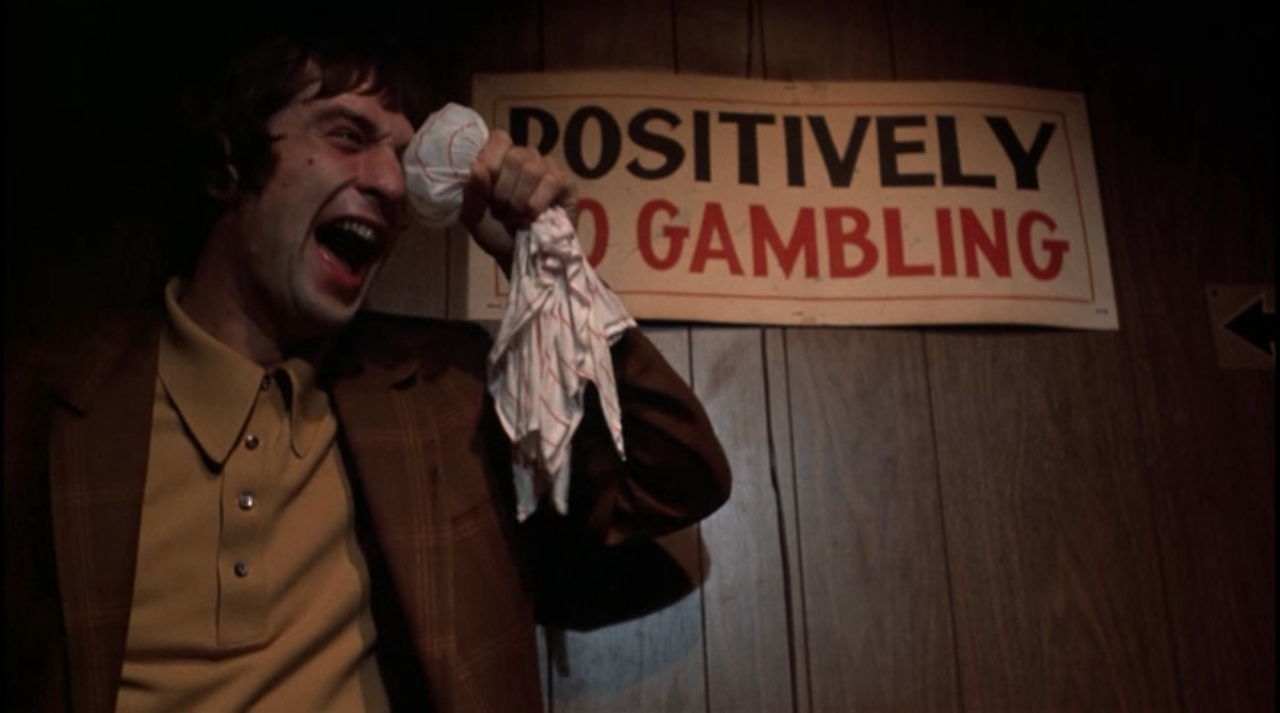

1. Mean Streets [above] (Saturday, BBC2, 11.40pm)

2. The Master (Saturday, C4, 12.45am)

3. Good Kill (Wednesday, C4, 1.30am)

4. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (Sunday, C4, 10pm)

5. You've Got Mail (Sunday, ITV, 12.40pm)

2. The Master (Saturday, C4, 12.45am)

3. Good Kill (Wednesday, C4, 1.30am)

4. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (Sunday, C4, 10pm)

5. You've Got Mail (Sunday, ITV, 12.40pm)

Into the sunset: "Lucky"

Everything about Lucky suggests it was set up as one final lap of honour for the late, great American character actor Harry Dean Stanton. It's co-written by Stanton's friend and former assistant Logan Sparks; a handful of the actor's associates show up to share a few scenes with the belatedly promoted lead; the director is John Carroll Lynch, who surely knows a thing or two about the vagaries of being a career-long supporting performer. (Lynch is perhaps best known for portraying the most likely killer in David Fincher's Zodiac.) Stanton, to the last, remained Stanton, the weatherbeaten oldtimer with the bow-legged walk of someone who spent much of his early screen time on horses, the actor's actor who made his debut for Hitchcock, became totemic during the New American Cinema of the 1970s, then moseyed along through Paris, Texas to Twin Peaks, living, breathing reassurance that no film, no project - not even Alien Autopsy with Ant and Dec - would be entirely dreadful so long as he popped up for a few minutes. He's pretty much the whole show here, playing the eponymous Texan, a not un-Stanton-like independent soul - almost more spirit than human, a ghost of movies past - whose set routine is interrupted by signs his considerable good fortune, which has previously granted him the freedom to smoke a pack of cigarettes a day without lasting health effects, may just be running out.

One settles in for a US indie variant of those eccentric Brit crowdpleasers that emerged in the wake of The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, slightly-to-extremely indulgent of their ornery protagonists. If Lucky far exceeds those initial expectations of fluff, it's in part because Lynch restricts his film to a no-frills, no-fuss, yet ever-eloquent and expressive description of one man's way of life. The spiritually inclined might call it Zen-like: we're merely invited to watch Lucky sitting in a diner doing the daily crossword, taking three hefty spoons of sugar in his coffee, getting back home in time to watch his shows (sorry Noel: a passing burn suggests Stanton was no fan of Deal or No Deal's inane complexities), sloping round his home and garden in boxer shorts and cowboy boots, knocking back Bloody Marys at the local watering hole. Lucky's primary subject is Stanton, this man, that (part turtle, part Buster Keaton) face; but its secondary field of study is the seemingly infinite downtime that stretches ahead of us after the working life is done, a liberation to some, to others a limbo. It wouldn't be hard to see the approach of death in this Tuesday afternoon-shaped void: the film marks its halfway point with a sequence in which an ashen-faced and impossibly lonely-looking Stanton tucks himself into bed to the accompaniment of Johnny Cash's "I See a Darkness", inspiring viewer thoughts that this may perhaps be one last, grave sleep.

Still, as our hero says in the wake of an earlier fall, "let's not make a production out of it": rest assured that it isn't. Instead, Lynch keeps ushering his star into unexpected encounters, knowing that it's often enough, from a cinematic perspective, to corral kindred spirits or different energies and personalities into the same frame. There are cherishable contributions - in the type of bit-parts Stanton once made his own - from the director's namesake David Lynch (no relation), making arguably his most normal screen appearance of all time, albeit in the role of a man who's lost a pet tortoise named after President Roosevelt; from Ed Begley Jr. as a straightshooting physician; and from Tom Skerritt (another of those supporting players it's a pleasure to see up and about, and in steady employment) as a fellow combat veteran with whom Lucky shares a few memories over a cup of joe. The film's love of such conversations - its sincere belief that two people jawing, or one man sparking up, can in itself be the basis of a moving picture, and possibly even communicate an entire worldview - finally positions Lucky closer to such semi-improvised indie-heyday experiments as Wayne Wang and Paul Auster's Blue in the Face or Jim Jarmusch's Coffee and Cigarettes: a certain lineage, not just in acting but film, is being honoured here.

That inbuilt looseness, though appealing and even rather charming over time, can feel somewhat disorienting for any viewer accustomed to template screenplays and unashamedly proscriptive indies. Deep into Lucky's final half-hour, we find the title character pottering around pet stores and playing the harmonica, showing up at a kid's birthday party to trill a song that might be an encore, while Lynch's camera drifts away to study the fireflies gathering in this guy's window; you keep expecting the film to go in one particular direction, and it never quite does, which may be as good a description of the Stanton oeuvre as any. (Again, I refer you to Alien Autopsy.) What you'll likely take from Lucky is some understanding, however tangential, of what it was to have been (or been around) Harry Dean Stanton, and what it was to have been lucky enough to have been (or been around) Harry Dean Stanton: to have grown to a ripe old age, been liked and respected by one's peers, forgiven for any grouchy outbursts or intemperate behaviour along the way, and able to have lived, died and, in the meantime, worked on one's own terms. If that alone doesn't bring a smile to your face and a tear to your eye, the film's final tip of its hat to this old cowboy walking into the sunset almost certainly will. Hard as it may be to believe in 2018, the movies are still capable of doing right by the people who've sustained them all these years.

Lucky is now showing in selected cinemas, and streaming via Curzon and the BFI.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)