The world hardly needed any more division, but 2020 – for obvious reasons – did its best to split us all into two distinct camps: Pessimists and Optimists. For the Pessimists, 2020 was A Very Bad Year, in cinema as much as anything else. The Coronavirus pandemic shuttered multiplexes and independent venues alike, putting jobs at risk, and even when it sporadically relented and cinemas reopened, what had traditionally been perceived as a fun, safe space no longer seemed quite so fun, or so safe. Sitting through an hour of pre-film adverts, always a trial, became only more so while wearing a mask; worse were the fears prompted by other patrons’ failure to mask up.

For the Optimists, however, the year was different in a positive sense. The abandonment of the multiplexes and the absence of their expensively trashy, discourse-dominating junk-movies opened up cracks for more delicate creative endeavours to sprout through, films that might otherwise have been trampled underfoot in the race to see Fast & Furious 38. Independent distributors recognised that locked-down audiences were compelled to gamble on titles they maybe wouldn’t have pre-Covid; consequently, 2020 yielded the most diverse release schedule I’ve encountered in my twenty years as a working critic. “This was a Pizza Hut,” sang David Byrne in Talking Heads’ (Nothing But) Flowers. “Now it’s all covered in daisies.”

The year began with a rare pleasant surprise: Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s satirical thriller Parasite triumphing at the global box-office, and beating more fancied rivals to become the first foreign language film ever to win the Best Picture Oscar. Yet when the film reappeared five months later in a black-and-white version, the world had changed. We were all being outflanked, and quickly. On January 20th, I attended the press screening of The Rescue, an extravagant soap opera intended as the centrepiece of China’s New Year celebrations; within 48 hours, the film had been shelved indefinitely, as the virus swept through China, making cinemagoing – and celebrating – an impossibility.

The West laboured under the illusion of normality for a while. There were multiple costume dramas (Sam Mendes’ WW1 endurance-run 1917, Armando Iannucci’s sprightly take on David Copperfield, a new, well-tailored Emma); a Bad Boys sequel; a savvy Blumhouse update of The Invisible Man. By March, however, it was clear sitting inside with strangers was becoming a non-starter. The new Bond film and Disney’s Mulan were delayed, early signs of a tectonic shift. On March 10th, I watched the knockabout Dave Bautista vehicle My Spy – a fairly shrugging way to send off the old world. I wouldn’t set foot inside a cinema again until August 19th, for a screening of Tenet. (We’ll get to that.)

So what did we do instead? If this crisis has demonstrated one thing, it’s the importance of rapid, flexible responses. The studios, like some governments, hesitated, panicked or insisted on acting as if everything was normal – big mistake. Streaming services filled the vacuum, providing some measure of escape from the grim business of daily death counts. Imagine how dire lockdown would have been if Covid-19 had been Covid-87 or Covid-94, pre-Internet, pre-iPlayer, pre-Amazon Prime. I don’t doubt there were those throwbacks who retreated with only a book and candlelight to read it by, but the rest of us were blessed with a dizzying choice of options, all without the risks now attached with leaving the house.

Instead of a summer of stultifying event movies, nimbler, more imaginative world cinema held sway. From Iceland, two superb dramas, The County and A White, White Day. From the warmer climes of Chile, the shifting, unpredictable dance movie Ema. The streaming platform MUBI laid on a season of New Brazilian Cinema, and several of the most esoteric films ever to appear on the UK release schedule. Seduction of the Flesh saw a writer set about wooing a parrot. Now, At Last! watched a sloth climbing a tree for forty minutes. We weren’t going anywhere fast, either, so why not? That once-hidebound schedule began to assume a look that was – dare I write this, as the UK backs decisively away from Europe? – more than a little French.

The independent sector stepped up – but then its hardy producers and distributors have long been used to operating in suboptimal conditions. From the US, a run of glittering streaming delights, both tough (The Assistant, Clemency, Shirley) and tender (Miss Juneteenth, Saint Frances). The UK witnessed a run of debuts so forceful that they became a keystone of BBC2’s Saturday night line-up when the channel ran out of new TV to broadcast: Make Up, Perfect 10, Lynn + Lucy. And no filmmaker seized the moment more than Shrewsbury’s Rob Savage, whose inventive Host [above] – accentuating the horrors of lockdown Zoom calls – became a cult streaming hit that earned the film a theatrical release and its maker a gig within the studio system.

Which brings us back to Tenet, positioned upon its UK release in August as a potential saviour of cinema – or at least of a particular kind of cinema. Overlong and mechanically mirthless, spinning us around the globe merely to flaunt its wealth and logistical clout, Christopher Nolan’s film proved no more than a relic of the old world, something for multiplex devotees to cling to, wherever multiplexes were still open. Scraping back its $205m budget, it saved nothing, really: by year’s end, Nolan was blasting backers Warner Bros. over their decision to send their entire 2021 slate to the streaming service HBO Max, in the absence of any full-time theatrical solutions.

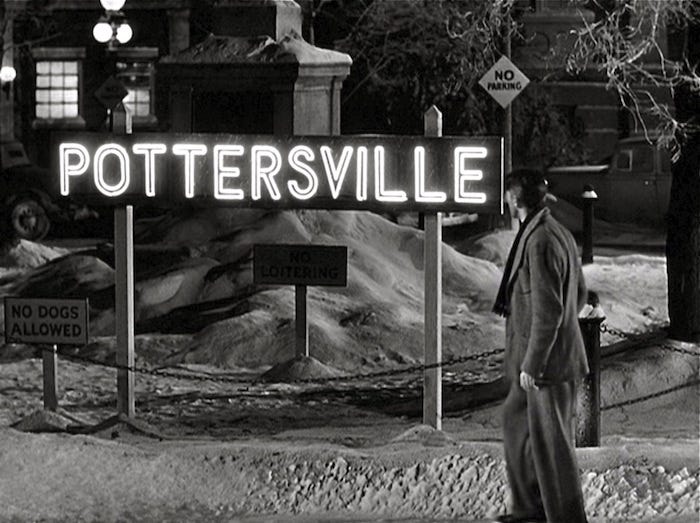

Which is where we are now. A second wave brought a second lockdown, and a funny-strange period where the only cinemas reporting for business were in Scotland and Wales, meaning the UK box office could be topped by a documentary about football managers (The Three Kings) which took £51 on its opening weekend. Last month, the compelling but tough Romanian documentary Collective opened at number 3, just ahead of the residual Liam Neeson actioner Honest Thief. As I write, the box office is being topped by a 17-year-old Will Ferrell comedy, Elf, one of several reissues offered up as the best the mainstream has to offer in the absence of bigger, fresher titles. Welcome to post-Covid Bizarro World, where business as usual really isn’t an option.

There will be an awards season, it seems, although this year’s contenders will have played in fewer cinemas than any of their immediate predecessors. The current frontrunner, David Fincher’s Mank, belongs to Netflix, as do Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods, George Clooney’s The Midnight Sky and Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7. Borat 2 popped up on Amazon Prime. Hamilton went to Disney+, as did Mulan and Pixar’s glowingly reviewed Soul. Cinematic optimists among us will point to a vaccine, and a longed-for resurrection of normality in the Easter, when we’re finally due to meet again with Mr. Bond. By then, cinema as theatrical event will surely need a shot in the arm – though, much like the rest of us, it may have to wait for it.