The Master (15) 137 mins ****

Rust and Bone (15) 120 mins ***

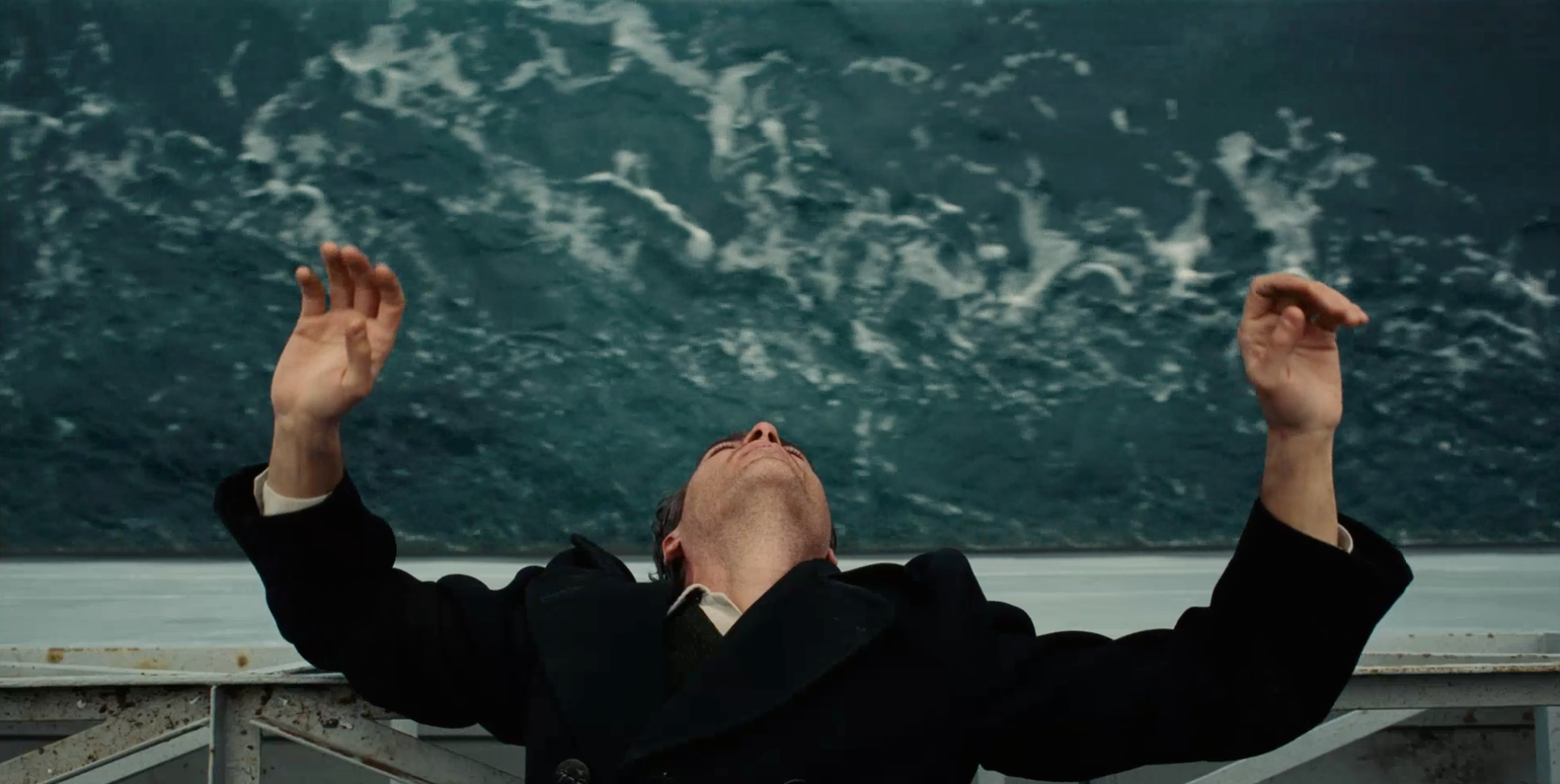

The protagonist of Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master is a sailor who, even on dry

land, finds himself adrift. Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix) emerges from navy

duty at the end of WW2 with only a crippling drink problem to his name. Not for

Freddie the upwardly mobile trajectory of post-War consumerism. Instead, he

bobs from job to job, learning only that the photographer’s darkroom provides

ideal cover (and ingredients) for cocktail-mixing, and that it’s not good form

to poison your fellow cabbage-pickers with cheap grog. “Get Thee Behind Me,

Satan”, from Follow the Fleet, floats

on the soundtrack: whichever way Freddie tacks, he’s a man pursued by demons.

The sea, meanwhile, continues to call. One night,

Freddie stumbles aboard the boat of one Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour

Hoffman). The founder of a crypto-scientific organisation referred to as “The

Cause”, Dodd modestly bills himself as “a writer, a doctor, a nuclear

physicist, a theoretical philosopher – but, above all, a man”. Upon hearing

such an introduction, you or I would doubtless jump ship, but then we wouldn’t

have a quart of paint stripper rolling around in our guts. Freddie is easily

taken in, but not so easily quelled; where a calming, feminine influence might

help, instead he’s made subject to Dodd’s provocation and power games.

Is Lancaster Dodd modelled on L. Ron Hubbard, who

founded Scientology in 1952? Our lawyers insist you decide. The Cause solicits

those with more money than sense; its followers’ belief in a cosmic conflict “a

trillion years in the making” doesn’t sound so far removed from Battlefield Earth. Yet wherever they

came from, Dodd and Freddie absolutely fit the framework of Anderson’s

perfectly controlled films about the limits of masculine control: think of

cocksure Tom Cruise, undone by emotion in Magnolia,

or Daniel Day-Lewis’s oilman Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood, succumbing to capitalism’s most monstrous

excesses.

Anderson allows this new film a scene-to-scene

spontaneity, but a certain steeliness of vision runs through it. Freddie is a

more difficult character than even Plainview: Phoenix, in a display of skilful

shambling, slurs through his dialogue, flags up Freddie’s essential puerility,

and rarely seeks our sympathies. The usually genial Hoffman similarly operates

at arm’s length. Part figurehead, part showman, he’s Joe Stalin playing Oliver

Hardy, slicking down his tie and eyebrows with an iron fist – and Anderson

refuses obvious satire by making Dodd as terrifyingly credible as he is

deluded. There are reasons why the Hubbards of this world exercise power.

Increasingly, Anderson’s films are leaving behind

the surface falsity of the entertainment industry, so magnificently described

in Boogie Nights and Magnolia, in favour of the elemental:

sand, wood, waves, characters who scrabble in the dirt. He, too, has been

digging – into pornography, then capitalism, now religion, each time bringing a

keenly critical eye to scrutinising our needs and desires. The conclusions he

uncovers in The Master aren’t always

comforting, but there’s no-one currently working in the American cinema telling

stories more important to where his society is at, and there’s no-one telling

these stories better.

The drifters in the oddball French romance Rust and Bone are of the contemporary

variety. Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts) arrives in the South of France, leaning

heavily on the hunter-gatherer instincts he’s honed as a sometime boxer. Of

nurturing qualities, however, he has none, as witnessed by a regrettable

tendency to knock his young son around. Enter the mollifying Stephanie (Marion

Cotillard), an animal trainer at a nearby water park, whose fate is coupled to

the wet stuff like hydrogen to oxygen. The couple meet after a nightclub fight,

when she provides ice for his swollen fists; when a bizarre killer whale

accident deprives Stephanie of her lower limbs, it’s to Ali that she turns.

Gone is the gruelling realism of director Jacques

Audiard’s earlier A Prophet, replaced

by Oz-like fantasy. Ali is the

strongman in need of a heart; our Steph is all that, but hasn’t a leg to stand

on. That Rust and Bone is both

striking and strangely resistible can be attributed to the way it pushes the

idea of opposites attracting to a borderline preposterous extreme. The question

Audiard’s film boils down to is simple: could you love an incredibly beautiful

woman with prosthetic limbs? The answer’s yes, of course, but it takes another

hour for Ali’s knuckle-dragging cerebrum to formulate this response. Sentient

lifeforms might spot that this is no ordinary pick-up, but Marion Cotillard;

hell, even the killer whale was trying to devour her whole.

The Master opens at the Odeon West End, London this weekend, before going nationwide on November 16; Rust and Bone is in selected cinemas.

No comments:

Post a Comment