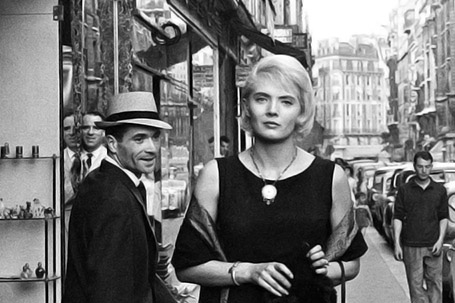

With the release of The Beaches of Agnès alongside two boxsets of her finest hours last year, Agnès Varda has made as prominent a cinematic comeback as any director over the past twelve months. That revival looks set to continue with a BFI Southbank retrospective this summer, and the re-release of 1961's Cléo from 5 to 7, Varda's international breakthrough. The tall, striking Corinne Marchand is Cléo, a Parisian singer who pops out for a couple of hours while awaiting the results of a test for stomach cancer, only to see reminders of her own mortality just about everywhere she looks. Varda's camera, meanwhile, becomes as fascinated by these signs and signifiers as was Godard's around this time (JLG has a rare acting role in a short-film-within-a-film, casting off his trademark lunettes noirs to woo and win Anna Karina), although here they're far less concrete - Tarot cards, superstitions ("you must never wear new clothes on Tuesday") and other arcane showbiz beliefs (reading reviews is "like saying Happy Birthday in advance: it brings bad luck") - and we're free to make of them what we will. What we're watching, essentially, is one woman's life passing before her very eyes, in something approximating real time.

By presenting us with multiple perspectives on these pivotal two hours - it turns out not just to be Cléo's story, but the story of everyone else she meets on her travels - the film now appears to predict our social network era, but it also deserves to enter into movie history for its thoroughly modern heroine, perhaps the first of her kind in French cinema. Marchand's Cléo is a celebrity (a commodity, even), with a tremendously chic apartment (tiny kittens, matching hot water bottle), but even greater needs; gnawed away from within by doubt if not necessarily by the cancer she fears, she's obliged to negotiate the twin worlds of art and politics (Algeria looms larger here than it does in many other early New Wave features) on a quest for the ever-elusive happiness that might ease the ache at her centre. Intellectually and geographically curious - it wanders and it wonders, a predecessor to Richard Linklater's Before Sunrise/Sunset diptych - it's as playful as any other early evening spent on Varda's shores, albeit with sudden swells of emotion that rise up out of nowhere: the lament Cléo's songwriters have her perform, and a bittersweet final leavetaking, position this director, once again, at the very heart of the New Wave.

(April 2010)

Cléo from 5 to 7 launches the Gleaning Truths season with a Q&A event at Curzon Soho, London this Thursday; it then returns to selected cinemas from Friday.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59411107/HA_03102_CC.0.jpg)