Saturday 31 October 2020

1,001 Films: "Buffalo '66" (1998)

Friday 30 October 2020

For what it's worth...

My top five:

1. Ghosts of War

American horror story: "Shirley"

Indie writer-director Josephine Decker first came to this viewer's attention with 2014's Thou Wast Mild and Lovely, a film notable for providing the cinema with its first cow's-eye POV shot. Here, clearly, was a creative with a novel perspective on the world. Decker went on to 2018's Madeline's Madeline, very much its own thing, whether you found that exhilarating or excessively hipsterish; now she moves in further from the indie scene's wild and woolly fringes with Shirley, which invites filing under the category of literary biopic. Not easy filing, however, and not always easy viewing. As befits their subject - the author Shirley Jackson, best known for penning The Haunting of Hill House - Decker and screenwriter Sarah Gubbins, drawing on a 2014 fiction by Susan Scarf Merrell, have presented us with a horror story of sorts. In Fifties America, a fresh-faced couple - young academics Rose and Fred (Odessa Young and Logan Lerman) - arrive at an old dark house full of nasty secrets; gradually they come to realise the worst about their hosts. Little do they know the man of the house, Professor Stanley Hyman (Michael Stuhlbarg), has half an eye on the newcomers as hired help, recruiting the pregnant Rose to cook and clean while the male breadwinners are elsewhere. Nor are they aware how much their stay will be shaped by Stanley's all-but-housebound wife Shirley (Elisabeth Moss), and her fascination with a missing girl and Rose's swelling belly, twin sources of inspiration for her latest book. Instead of mounting a celebration of creativity, Decker puts on screen the demons that can dog it: the depression, the drinking, the doubt; the obsessiveness and control freakery; that leeching vampirism that tends to regard other people as predators do cattle. Nothing about Shirley is mild, and even less lovely; there are good reasons why a distributor might choose to open it over a Hallowe'en weekend.

In being drawn so conspicuously towards the extremes of the creative life, Decker's film has prompted demurring reviews from such literary-minded critics as Anthony Lane in The New Yorker, who was left wondering whether Shirley smears the Jackson name in taking the wild imaginative swings it does. To these eyes, the film's only crime is to acknowledge that writers can often be difficult sods, and then double down on it stylistically, a stance that carries Shirley far beyond even the intelligent but formally conservative Capote. At no point is this biopic allowed to slide into neutrality. Taking one (fictionalised) bad patch as a field of study rather than flapping around to provide a glowing career overview is but the first of the bold choices here: in a continuation of the Decker MO, these will fascinate some and repel others, but you can't deny those choices have been well and truly made. For starters, the Jackson-Hyman house is very old, very dark, horribly cluttered: we sense Rose could pass a Hoover around it for months, and still it wouldn't make much in the way of difference. Madeline's Madeline played out in brightly lit rehearsal spaces before finally spilling out onto the streets: it came at the viewer from the perspective of a young woman at the beginning of her career, with energy to burn or remodel the world to her liking. Shirley, a vastly more mature undertaking, takes place in the pit of despair its prematurely middle-aged subject has dug for herself or been abandoned to - and one of its achievements is to get us to consider the fate of a cultured yet depressive woman in the narrow world of Fifties academia. ("Shirley, you're too much," chuckles a nervy fellow at the faculty ball - that's the issue here, and this Jackson's tragedy.) When we head into the woods, it's so the writer can spook her childbearing roomie with threats to consume a deadly mushroom and end it all; even the sorority girls in their brightly coloured sweaters - markers of health-and-efficiency in more conventional period pieces - are reconfigured by night as a witches' coven, one of several loaded Shakespearian references.

The material demands performers willing to plunge into that pit and fight tooth-and-nail for these characters; who give us reasons to get involved, and venture onward into the darkness. Our way in is Stuhlbarg, the supporting actor's supporting actor, who makes Stanley clubbable without hiding how that clubbability masks a rage born of an understanding - accentuated by his youthful lodgers - that he's getting old and going nowhere. Lerman, an upright tie-pin, has been nicely cast as the picture of Fifties squareness; Young, who's something like an earthier Natalie Portman, is a small revelation, submitting to Rose's Single White Female-like remodel in Shirley's unforgiving image while wondering why it is she's going to miss this monster when she finally has to move out. She is, admittedly, quite the monster. I spent the summer revisiting The West Wing, so it was doubly shocking to re-encounter sweet-faced Zoey Bartlet as one so fundamentally sour, but this speaks favourably to Moss's growth as an actress, her willingness to push audience sympathy to the limit. Decker sticks her Shirley with the glasses, hair, skin and wardrobe of a small-minded curtain-twitcher, but the transformation isn't merely superficial; Moss summons a colossally bad attitude, such that even when the muse is with her ("So the writing's going well?") she can but respond with snarls ("Don't ever ask that again"). Does the film slander Shirley Jackson? I don't think so. At the very least, Shirley makes us marvel all the more that the writer expressed herself so civilly on the page; and we take away a perversely touching sense that - with the male academics away, at work and at play - this Shirley teaches Rose something about her struggles that will make her pupil less inclined to suffer any more BS going forward. (The liberations of the Sixties and Seventies await her; Jackson died in 1965.) All Gubbins and Decker have done is separate the art from the artist, and paid a heightened attention to the beetles and bugs that scuttle out in the process, as they would scuttle away from a corpse being removed from a crime scene. It isn't always pretty, and it may send shivers down the spine of even non-writers, but - as confirmed by an inspired sound choice over the end credits - there is a squirming, insectoid life to behold here; that life, unlovely as it is, allows Shirley to define itself - triumphantly, I think - against the lifelessness of so many biopics.

Shirley opens in selected cinemas, and is available to stream via Curzon Home Cinema, from today.

Thursday 29 October 2020

Mixed media: "The Painter and the Thief"

Yanked from the "when worlds collide" file, Benjamin Ree's documentary The Painter and the Thief offers an altogether sobering lesson in human nature. The painter of the title is Barbora Kysilkova, Czech-born but Norway-based, first seen enjoying a small triumph with a show of her darkly shaded canvasses at a gallery in Oslo, where she lives with her husband Øystein. The show was prematurely halted when two thieves broke into the gallery - Ree has the CCTV footage - and made off with a couple of the most prominent works. Surprisingly, Kysilkova reached out to one of the thieves, Karl Bertil-Nordland, during the trial, with an eye to discovering the whereabouts of the still-missing paintings; Bertil-Nordland insisted he was in a drug-fuelled haze at the time of the crime and thus retains no memory of where the artworks went. Nevertheless, he agreed to sit for the painter, firstly in a "Fat People Are Hard to Kidnap" T-shirt, later in a shirt bearing the legend "Crime Pays". Even a Norwegian parole board would peg his chances of rehabilitation somewhere in the vicinity of 10%. Ree set his camera up in Kysilkova's studio for the duration, serving both as stenographer and safeguard, and noting a growing bond forming between dreamy artist and light-fingered muse. In a voiceover full of the best liberal intentions, Kysilkova admits she can easily imagine her latest subject as either a suicide bomber or a future Prime Minister: to her, Bertil-Nordland presents almost as a lump of clay, to be moulded and made pliable, perhaps so she can push her thumbs in and extract the info she wants. We shouldn't be too amazed that things got as sticky as they did.

Other elements here are more surprising, though it's best I leave you to discover those for yourself. You need only be aware going in that Ree befriended both parties, which allows him to cut between perspectives, and show us what Bertil-Nordland was getting up to on those afternoons when Kysilkova wasn't arranging him into poses on her chaise-longue. We're drawn into two worlds simultaneously: that of the boho dauber whose goodness extends to laying flowers on an unmarked grave, and the far less settled milieu of the junkie-thief who refers to himself as "The Bertiliser", has clearly been badly hurt at various points in his life, and has emerged from that with an enduring need for the kind of stimulation that can only be found on the streets. (Going out for what proves a fateful drive, Bertil-Nordland confesses a desire for "a couple of kilometres of thrill".) The quiet observation allows us to notice how blithe the painter's phone calls are to the thief, and the mobility even a relatively penniless artist takes for granted. Ree positions himself as a midpoint between worlds, a third party who sees two friends getting into something, senses it may make for bumpy travel, but feels compelled to stick around - if only to try and keep everybody safe. He's in it for the long haul, to his credit: we'll see not just the shape of a portrait, but several lives change. Yet he's judicious about what he enters into evidence, which may raise a few eyebrows. It struck this viewer as curious that Øystein - Kysilkova's bedrock after an earlier, abusive relationship - is kept offscreen after his introduction; but clearly Ree wanted everyone to get in too deep before attempting any kind of intervention. This is a documentary that requires viewer patience - its circling round is that a painter undertakes before committing to making a decisive mark - but once Ree applies the first splashes of harsh, bracing life experience, you will want to know how this portrait turned out. I offer this not so much as a spoiler but by way of reassurance: it's better than I was expecting around the halfway mark. People have a funny way of working things out when they have to; it's one of the few sources of hope we have left.

The Painter and the Thief opens in selected cinemas, and will be available to stream, from tomorrow.

Wednesday 28 October 2020

Wait and see: "The Young Observant"

MUBI UK's latest discovery from Locarno, Davide Maldi's documentary The Young Observant, is a film of strange rituals. I guarantee you will spend its first five minutes wearing a puzzled expression. Why are those middle-aged men measuring that teenage boy's ears, scraping his cheeks with a credit card, instructing him to literally pull his socks up? I know old-school fascism is back on the rise in Europe's dimmer corners, but have the eugenicists made a comeback nobody told us about? Even after Maldi sets out some reassuring context - that the kid, mostly referred to by his surname Tufano, is a student at an elite catering academy, being tested to determine his precision, thus his ability to become a waiter, barman or maître d' - the rituals keep coming. If you're looking for a film to teach you the accepted way to mix a Martini or fritter a banana, you've come to the right place. Yet what's striking is that we can't be sure Tufano has. He's trying hard, as we discern from his earnest answers to a question about the differences between the French and Finnish hotel classification systems. Yet he is, by his very nature, a restless soul, from his unruly shock of auburn hair to his tendency to drift off in his head during class. "People make me sick," he blurts out during one lesson. "I don't like people." You worry he's less likely to pull out a chair for a patron as he is to smash someone about the head with a skillet.

In short, Maldi's film has all the right ingredients for involving non-fiction: it leads us into a rarefied world, identifies someone who seems out of place there, then sets us to wondering whether relentless drilling can convert this malcontent into a willing and able public servant. As the sporadic thump of militaristic drums on the soundtrack underlines, it's really a bootcamp movie, the hospitality sector's equivalent of Full Metal Jacket. In the circumstances, the heart can't help but go out to the rough-edged Tufano, who comes this way as an outsider. Unlike his classmates, all of whom seem to know someone with experience of glass polishing and napkin-straightening, he's a complete novice, a loose amalgamation of raw material of a kind the camera has forever been drawn towards, either because calamity awaits (he's not much use with trays) or because he's so entirely himself, unable to mask his frustration, boredom and resentment. We learn in passing that he lives in the mountains, which possibly explains his vague air of loftiness and resistance to other lifeforms, but also his tenacity, his ongoing, uphill struggle to better himself. There are points where he appears less a documentary subject than a character in a bildungsroman: if Maldi hadn't stumbled across him, someone would have had to make him up.

Some elements of his progress do look to have been constructed or recreated, like an after-hours meander around the academy's corridors, the kid's pocket torch alighting on a taxidermy collection that would be terrifying enough encountered in daylight hours. Yet even that sequence works towards a better understanding of what an odd place this is for a country boy to find himself in: we might consider, as Tufano surely considered, whether the academy's goal isn't to hollow its scholars out and similarly reduce them all to posed, stuffed shirts. Maldi's day-to-day observation is in itself revealing and fascinating. It becomes obvious from around the halfway point that Tufano is better at the hands-on aspects of this career path than he is at the theory, which is why he looks so bored at his schooldesk, and gets so truculent at the white board. (The happiest we see him is when he's pulled out of lessons to wipe down a kitchen door: he says it reminds him of milking cows.) Frame by frame, a once proudly defiant head drops; Maldi shows how potential mishandled can quickly result in a problem case. The conclusion's one of the most ambiguous you'll witness all year, but The Young Observant carries us there with uncommon reserves of human interest, and a subtle philosophical bent. Discipline is all well and good, Maldi knows, but his film also acknowledges that - even within the absurdly specialised field of waiter training - individual students require individualised instruction.

The Young Observant will be available to stream from tomorrow via MUBI UK.

Tuesday 27 October 2020

Animal crossing: "Now, At Last!"

Sneaker pimps: "One Man and His Shoes"

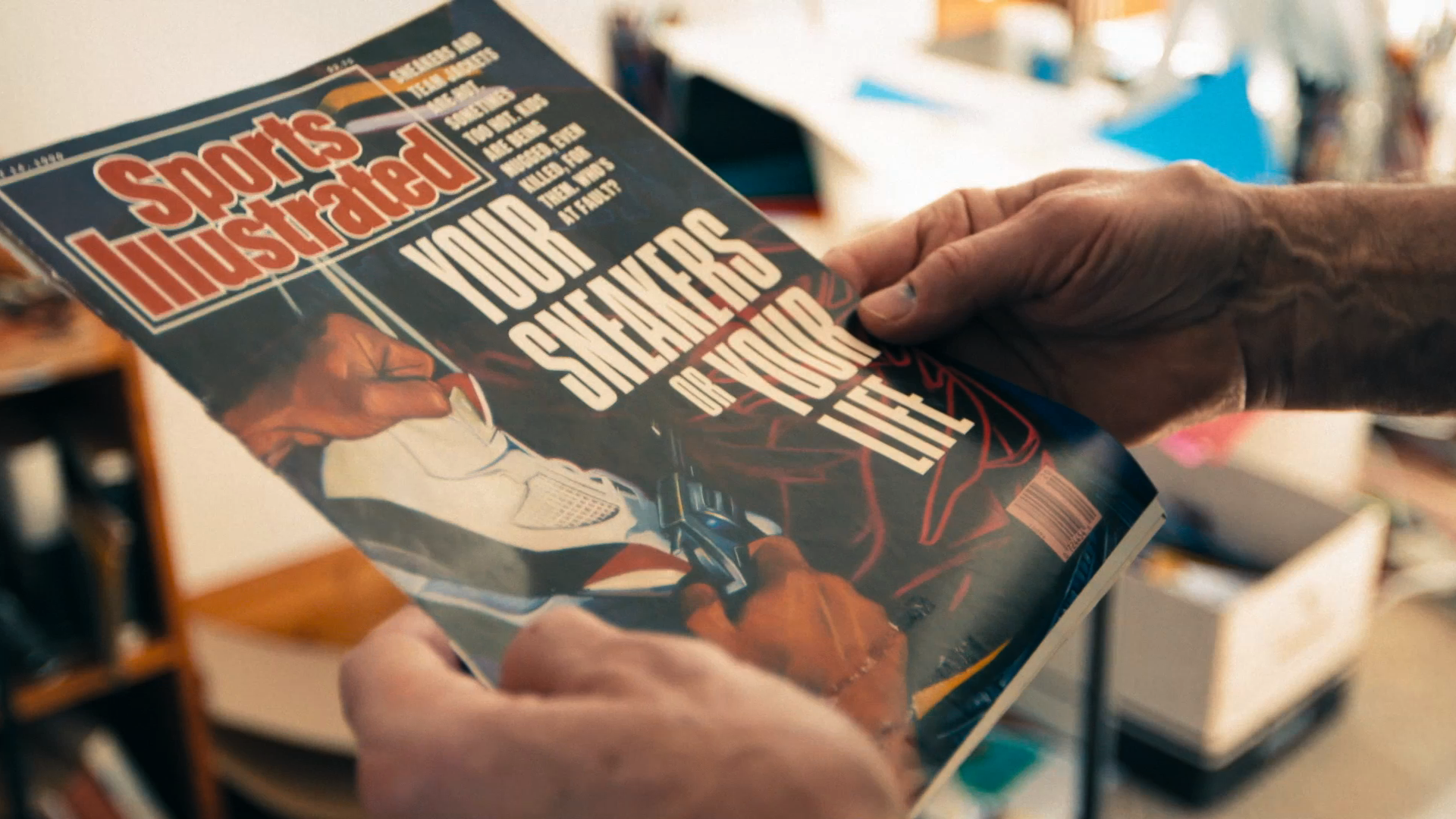

The success of Netflix's The Last Dance has reawakened an interest in the life, career and endorsements of basketball superstar Michael Jordan: new doc One Man and His Shoes is opening in the UK a week before the revival of a 2000 IMAX special going under the none-more-Nineties title of Michael Jordan: To The Max. (We also have that Space Jam sequel awaiting us next summer.) Yemi Bamiro's film has one very specific aspect of this legend in its sights and on its feet: it's a history of those Nike trainers to which Jordan lent his name. Yet Bamiro comes this way with a fair bit on his mind, which may be why the results feel so scattered. These 83 minutes aren't merely about running shoes, but how Air Jordans sat at the centre of a nexus of race, celebrity, politics, corporate branding and popular culture. You'll need some tolerance for footage of CEOs and agents sitting around well-furnished homes talking with pride about the deals they struck to ensure a young athlete was handed staggering sums in return for wearing freebie trainers - it's predominantly a money story, and one that has to position Nike as a plucky underdog in order to sketch the narrative arc it wants for itself. Despite Will Newell's jazzy graphic design, much of that positioning is achieved within a conventional talking-heads format. Yet it has a secret weapon in Bamiro's confident marshalling of the ephemera these deals generated, the print ads and promo spots that did almost as much as Jordan himself did on court to secure his public image. It means to sell you on a non-essential item that would swallow your monthly salary and be obsolete within the year, but the double-page image of Jordan mid-air and mid-dunk remains an eye-catcher; and "Michael Jordan 1, Isaac Newton 0" is tremendous copywriting, wherever you're coming from. And that's before Bamiro works in those zippy, Spike Lee-directed campaigns by which Nike started to run rings around their sporting rivals, with their lame "rapping athlete" spots. (It's a bit like discovering Public Enemy on the same chart as the "Anfield Rap".) Still, from an early stage, there are tensions beneath the film's surface that Bamiro never fully resolves.

Granted, they were there in the original story, which was that of corporate America making one young Black man a star, and bestowing unimaginable riches upon him; riches that were solicited, in great part, from impoverished inner-city children for whom a $180 pair of sneakers became an exit strategy, a status symbol, and - in certain cases, touched on late in Bamiro's film - something to die for. What was being sold with that Jumpman logo was an image of Black strength, beauty and success. (As those Lee ads regularly wondered: "Is it the shoes?") How that image squared with American reality is what matters, and it's here you sense Bamiro, making his feature documentary debut, getting muddled. He's outright distracted in those segments involving Air Jordan hoarders, a jolly quirk that makes for a crunching gear change when the film then confronts us with images of youngsters in deprived areas being mugged and killed for their footwear. Now we learn that Nike knowingly withheld from the supply chain so as to ramp up demand for their product; now we hear the lawyer for one grieving family denounce those ads the documentary has previously taken so much pleasure in as the propaganda of a corporation valuing profit over human life. It's either a structuring issue, or a failure of editorial nerve: to make the leap from fanboy to journalist, Bamiro really needed to take the footage he shot at Houston gravesides to the mansions of the suits he chuckles along with early on - or, indeed, to Jordan, a no-show who continues to cash the cheques - and to ask these powerbrokers how much responsibility they're prepared to take for Nike's moral failures. It's an angrier film than it lets on, I think; I wonder whether Bamiro was advised to make nice for much of it. He gets in plenty of coverage, but at some point he needed a pivot worthy of Jordan himself; in the absence of that, we're left with a film whose two halves don't quite fit, like mismatched pumps on the shelf of a Foot Locker backroom. We can still admire the design, but they make for uncomfortable travel.

One Man and His Shoes is now playing in selected cinemas, and streaming via Prime Video, Curzon Home Cinema and the BFI Player.

Monday 26 October 2020

Tumbledown: "Relic"

The generic boundary separating horror from drama feels especially thin and permeable during the new Australian film Relic. The creep of unease you feel while watching is the result of actual, relatable life processes rather than ramped-up movie chicanery; its haunted house is just a home that's been lived in a long while. Underpinning every one of director Natalie Erika James's images is the fear of getting old, and of seeing your loved ones growing old, incapable, and disappearing before your eyes. It happens to us all, and that's the scary part. For starters, James and co-writer Christian White introduce us to fresh-faced mother-daughter pairing Kay (Emily Mortimer) and Sam (Bella Heathcote), dispatched to a property on the greener fringes of Melbourne, where Kay's elderly mother Edna has been reported missing. There, they sit tight between tidying up rotting fruit bowls, begrimed windows and decades' worth of hoarding, falling subject to bad dreams and other bumps in the night. Worse follows when Edna (Robyn Niven) returns as suddenly and inexplicably as she vanished, in a blood-soaked nightie and with scars on her body, trailing the mystery of where she's been. Here is a common-or-garden dementia narrative - the stuff of a thousand afternoon TV movies - pushed to a dramatic and stylistic extreme.

It's been pushed gently, quietly and effectively, by a filmmaker who understands horror is one of the few genres where it often pays to go slow. We spend the bulk of Relic poking round this dishevelled household in the company of two recognisably modern girls (Mortimer and Heathcote, with but fifteen years between them in real-life, could almost be sisters; in this context, their youthfulness is the point) as they come to terms with the genetic curse hanging over this family. The horror sneaks in at night, and it's that of ageing and dementia itself, skilfully embodied by the 78-year-old veteran Nevin: the increasingly cranky attitudes, the violent lashing out at those who would care for them, and those carers' realisation that a person they love has been taken over by someone they don't know, and who neither knows nor cares about them. Edna's not a monster, rather human flesh-and-blood, in the grip of a terrible, incontrovertible thing. That cushioning compassion possibly precludes the oomph that made The Babadook both a rollicking night out and a runaway box-office sensation. Though Relic builds - declines may be more apt - towards a fraught finale involving an overflowing bath, an electric heater and a crawlspace that parallels a shrinking worldview, we're chiefly here to watch the rot setting in: production designer Steven Jones-Evans has come through with mildewed walls that in their own way reflect a diseased mind. Still, that process of decay has been very carefully thought and worked through, such that I could not discount Relic being a profoundly cathartic experience for anyone who's found themselves in a comparable scenario. As geronto-horror goes, it's a marked step-up from M. Night Shyamalan's puerile, flatly mocking The Visit.

Relic opens in cinemas nationwide from Friday.

Saturday 24 October 2020

For what it's worth...

2 (new) Michael Ball & Alfie Boe: Back Together (PG)

My top five films currently on release:

1. The Ladykillers [above]

My top five:

1. Ghosts of War

Top five films on terrestrial TV this week:

1. Babe (Saturday, ITV, 12.55pm)

The plague: "Totally Under Control"

Here's the week's other October surprise. Rather than baking sourdough, documentary busy-bee Alex Gibney has spent lockdown assembling a team of journalists (including co-directors Ophelia Harutyunyan and Suzanne Hillinger) to help chronicle the Trump administration's murderously inept handling of the Coronavirus pandemic. Opening in the US last weekend ahead of the most life-or-death election in living memory, and debuting on UK screens big and small this week, Totally Under Control - morbidly ironic title pulled from the lips of the President himself - sets out a detailed timeline beginning in January 2020, when the first cases of Covid-19 were reported in the US, and running through to April, by which point it had become clear that politics was getting in the way of science. Thus far, this combination of idiocy, complacency, pig-headedness and outright malfeasance has resulted in 200,000 deaths and counting. (And still the President bluffs, and golfs, and dances.) Trump was the bulldozer elected to tear down a system that wasn't working as America's very rich and very poor desired; reports suggest Covid has much the same effect on the human respiratory system. At a moment when the public looked to one to protect them from the other, they instead found them working hand in unwashed hand. Gibney doesn't even need to run his timeline through to the Amy Coney Barrett announcement event that caused a localised spike last month to seal his damning case: these two hours uncover ample proof that this President is a superspreader - of germs, BS, you name it.

It's a depressing backdrop, and Gibney dutifully rounds up the footage of cardboard coffins, mass graves, and the apparently abandoned cityscapes that have become so familiar in our new dystopian normal. His editorial line could scarcely be more disheartening: time and again, we're shown how those with specialist knowledge were routinely ignored, dismissed or sidelined by the White House. Yet Totally Under Control buzzes with the thrill that comes from pursuing a story and bringing it to wider public attention: it's yet another demonstration of this filmmaker's near-unique ability to plug the spectator into the hyper-accelerated push-and-pull of the 21st century, and to transmit all the intel anyone might need to make better informed decisions at critical moments. Gibney insists that in times of crisis, we should look to the experts; so - while operating within social distancing protocols - he sits down to interview those journalists, scientists and doctors who've acted in much the same manner as the UK's Independent SAGE group. Here are people who could clearly slow and stop the spread, if they were only given the chance. (One formal tic: Gibney shoots them approaching the camera as if they'd just returned home from a hard day's work.) It's a slap in the face, then, whenever the film cuts from these informed, articulate individuals to a leader of the free world who can barely string a sentence together - but that's where we are. Barely more impressive under close scrutiny is Trump-appointed CDC chief Robert Redfield, a middle-aged mediocrity who took such great delight in tossing out the pandemic playbook prepared by the Obama administration: another borderline-criminal instance of counterevolutionary system-trashing, compounded by an abject failure to provide such basics as, say, non-faulty testing kits or an effective track-and-trace plan. (Stop me if this is getting too close to home.)

As a producer and director, Gibney has signed his name to something like two-dozen projects in the past couple of years, the vast majority of which have bolstered our understanding of the way the world now turns. Once again here, you're led to wonder how he finds the time - and how he finds the time to do this so well. The specific conditions of lockdown must have helped, but Totally Under Control casts its net staggeringly wide, rifling through broadcast news footage, public health reports, several zillion Presidential Tweets, plus old karaoke clips (you'll see why), extracts from Red Dawn and one especially inspired use of C.W. McCall's rallying "Convoy" at a point where spirits might be flagging. Given the boundless ineptitude of this regime - administration now seems too competent an expression to fit - it's a minor miracle that Gibney kept the running time down to a manageable two hours. Yet that's part of the thrill: here is a documentary that never blusters or belabours its points, that grasps there is no time to lose. So where does it leave us? Clearly, the next month - with a second wave of infection sweeping in, and an election looming that will decide America's direction of travel for the next four years - will be critical. As one of those dinosaurs raised to believe that our leaders should be worth looking up to, I've spent the past four years wondering why anyone would cast their vote for a slob like Trump. But that may well be the appeal: that a crucial percentage of his voter base are those ground down by capitalism, re-energised by the opportunity 45 presented them to say and do the dumbest, nastiest things and receive no pushback for it whatsoever. It has been America's first anti-aspirational presidency. That'll do for a one-off, toys-out-the-pram electoral tantrum, but Gibney spies how it's enabled other forms of cruelty and incompetency (anti-maskism, for one) to creep into mainstream political discourse. What he also knows, and what Totally Under Control bears out, is that in an age of stupid, one form of resistance - more crucially, a way to survive - is to get smarter. Here is one of the few films you'll see this year that may in all likelihood save lives.Totally Under Control is now playing in selected cinemas, and available to stream via Prime Video, Curzon Home Cinema and the BFI Player.

Friday 23 October 2020

First love, last rites: "Summer of '85"

With Summer of '85, François Ozon successfully queers the pitch of the What I Did On My Holidays coming-of-age movie. Its title appears amid a big, splashy, nostalgia-prompting soundtrack cue (The Cure's "In Between Days") and over shots of a gorgeously sunkissed Normandy beach, but only after a muted prologue in which our boyish teenage hero, shackled in the corridors of a courthouse, confesses to having spent this particular summer putting himself in close proximity to a corpse. We may still be at the seaside geographically; existentially, we're a good deal closer to River's Edge. (Ozon's adapting Dance On My Grave, Aidan Chambers' UK-set young-adult novel of 1982.) So here are the in-between days, separating that from this: Alex (Félix Lefebvre), a skinny blond working-class virgin with a gift for creative writing, is plucked from the sea after a boating mishap by one David Gorman (Benjamin Voisin) - not that DG, rather a smiley older Jewish lad with a) a bigger vessel (some indicator of class) and b) an easygoing sexuality. Despite their subsequent bonding - nights out at the cinema and discotheque, rides along the seafront on the back of David's Suzuki, one of those rollercoaster rides that serve as movie shorthand for adolescent turbulence, knots in the stomach - there's a curious sense that Alex is being lured in rather than befriended; Ozon only heightens it by cutting between these bucolic flashbacks and the police investigation that marked summer's end. This once, our hero's narration isn't the basis of a school report, rather a witness statement; not for the first time on this director's CV, desire will go hand-in-hand with danger and death.

That filmography continues to veer all over the place, generically: Summer of '85 follows the sincere period drama of 2016's Frantz, the knowing trash of 2017's L'Amant Double and last year's true-life procedural By the Grace of God. Here, however, Ozon returns to the useful ambiguities of 2012's In the House, still a highpoint in this busiest of careers. Though the vaguely vulpine David seems the more forceful of the film's teen lovers, the opening sets us to wondering what a wormy, suggestible naif such as Alex might be capable of, and whether the account of these events he launches into in that prologue is entirely reliable. Ozon has measured fun with his setting - setting a fairground fistfight to the Europop song that became Laura Branigan's "Self Control" - but his aim is to revisit the very idea of first love, and to address it not as innocent bliss, but more complicated and often less healthy than the movies have traditionally reflected. Is this why Summer of '85 sporadically feels more punishing than pleasurable? Certainly, there's more psychological torment than the distributors have let slip on the poster: one grisly sequence has Alex envisioning the various methods by which he might do himself in. Nothing here will overturn the perception that Ozon has grown to become the neurotic's Almodóvar, too caught up in his own thoughts to paint the town red as he once did. (Cinematographer Hichame Alaouie instead leans into cool maritime blues.) Yet he's matured into a storyteller capable of depth - he coaxes touching work from Isabelle Nanty and Valeria Bruni Tedeschi as concerned parents, and from Philippine Velge as the English girl tangled up in the boys' affections - and surprises besides. I wasn't expecting to see Alex having to drag up as he does in the final third for reasons best discovered for yourself, but then I guess that's the Ozon idea of young love: sometimes it carries us far from the straight and narrow, and changes us in ways no-one can fully anticipate.Summer of '85 opens today in selected cinemas, and is available to stream via Curzon Home Cinema.

From the archive: "Get On Up"

Awards season, naturally, equates to biopic season. Where this year’s British contenders fuss over starchy bigbrains (Turing in The Imitation Game, Hawking in the forthcoming The Theory of Everything), their American counterparts inevitably skew towards showier figures. Given its subject, it would be a crime if Get On Up, Tate Turner’s James Brown biog, settled for a pussy-footing, cookie-cutter narrative; even so, you may have to brace yourself for the approach Taylor and screenwriters Jez and John Henry Butterworth actually settle upon.

This Papa’s got a brand-new grab bag: everything gets tossed in there, shaken around, and then tipped out to see where it lands. The first ten minutes alone offer a bizarre (yet apparently true) anecdote in which a PCP-blitzed Brown points a shotgun at a woman he suspects of using his toilet; a flashback to the singer’s time dodging sniper fire on a USO trip to Vietnam; and a further flashback to Brown’s impoverished childhood out in the wilds of Georgia.

It’s just possible the film intends to show us how one formative, disruptive experience nestles inside another Russian doll-style, but it plays as if the filmmakers were hellbent on giving us several James Browns for the price of one: in biopic terms, we’re caught somewhere between the multiple Dylans of I’m Not There and the abject scrambling of Ma Vie en Rose.

Amid the whirlwind energy, we can discern certain constants: violence, for one, or as much violence as a PG-13 biopic is allowed to depict. Young James’s father (Lennie James) himself pulls a gun on his wife Susie (Viola Davis) after she attempts to take her boy away from him; an early brush with showbiz – involving a gospel group touring the prison Brown was sent to for stealing a suit (a telling biographical detail) – ends in a mass brawl; in so far as the film engages with the singer’s women, it’s to show the singer beating second wife DeeDee (Jill Scott).

Mostly, this is a one-man show: whichever incarnation of him we’re watching, Brown always ends up looking into the camera, and out towards some imagined audience. This life was a performance, we soon gather – sustained in the same way Brown strung out songs in concert for as long as the rhythm section could hold out – and at the very least it’s yielded a Georgia peach of a leading role.

Chadwick Boseman, the actor who brought the talismanic Jackie Robinson to life in last year’s 42, doesn’t look much like Brown – he’s too elongated and upright to do justice to the squat figure caught on film in such documentaries as 2009’s Soul Power. But he sounds like him – all self-aggrandising patter, only partly comprehensible in places – and he has the smile and the swagger, and crucially the peacocking spirit.

That stolen suit, coupled with the shoes we see the young JB relieving from a lynching victim, is central to the film’s conception of Brown as pop’s greatest salesman, a shameless careerist who emerged from the South peddling soul rather than snake oil. Get On Up hits its most consistent notes in a run of scenes set during that late 50s period that saw the building of pop as an industry: Brown effectively becomes an independent contractor, selling out his band and striking up his one truly sincere relationship, with manager Ben Bart (Dan Aykroyd, a neat Blues Brothers connection).

We’re left watching the story of a man who overcame the turmoil in his life by exerting maximum control over everyone around him; how much we’re supposed to like anything other than the guy’s product is (deliberately?) obscured. Still, if the approach precludes any deeper understanding of who that guy was beyond the sum of some messy, unprocessed life experiences, Get On Up does have the not inconsiderable advantage of moving like James Brown: restlessly, sometimes stirringly, yet very much to the beat of its own drum.

(MovieMail, September 2014)

Get On Up screens on Channel 4 tonight at 11.30pm.

Thursday 22 October 2020

Tesla girl: "Max Winslow and the House of Secrets"

Wednesday 21 October 2020

Rock of ages: "Ghost Strata"

One indicator of how much more diverse and interesting the UK release schedule has been in 2020 compared to previous years: the newfound prominence of the free-floating British artist and filmmaker Ben Rivers. Rivers' essayistic feature Krabi, 2562 found its way onto the docket back in May, affording locked-down viewers a welcome glimpse of life in a Thai holiday resort; as that emerges on DVD, MUBI UK now premieres Rivers' 45-minute short Ghost Strata. Where its predecessor was bound up with place, the new film is more clearly about time. Its title refers to those shadows and absences in rockface that help experts determine a more complete picture of geological time, and what we're watching is effectively that which Rivers chiselled out of one twelve-month period, scenes recorded over the course of a single year. A visit to a fortune teller; birds circling a lagoon; a souvenir of a holiday in Greece; a memory of a bamboo forest. His soundtrack is equally variform: what we hear are snippets of audio uncoupled from the image, more often than not spectral stirrings from the past, with the interrupting snaps, crackles and pops to prove it. Put it together, and you get a film-diary or workbook, in the tradition of Jonas Mekas, albeit without any contextualising voiceover to bind its constituent parts together. We're left to interpret the whole as we will - indeed, its success may be largely dependent on your willingness to make those interpretations for yourself.

One advantage is that Rivers' eye has always been drawn to textured, tangible images, representing immediately intriguing ideas. The option is certainly there to tie yourself in knots thinking how all these loose ends connect thematically, but as in the director's best films, you could equally just sit back and enjoy the looking. For there is good looking to be had here: rock formations that resemble lunar landscapes or silent screams; details of paintings illuminated by an art historian; the extraordinary bits and bobs left behind whenever the Thames recedes. What Ghost Strata seems to be getting at is the way elements from the past come to speak through time to us. (One reason the world's now so noisy is that the past won't shut up: we have to make our peace with it just to hear ourselves think.) By the time the film reaches December, reuniting us with the actors who played cavemen in Krabi, 2562, we've been afforded a richer sense of Rivers' workings, how the R&D of Ghost Strata fed into the themes of the feature proper. One dreads to think how empty his 2020 visual diary must be, but Ghost Strata has assumed an extra, unexpected resonance for emerging at the end of a year where radios the world over have been pumping out a daily death count. Observing the film's transient glories, turning them over in the mind like pebbles, we are confronted once again by the realisation that whatever we might leave behind or set down by way of permanence, we are all just passing through, no more at the last than existential tourists. But what a guide and navigator Rivers is proving to be.

Ghost Strata is now streaming via MUBI UK.

Golly: "Raise Hell: The Life & Times of Molly Ivins"

Colossal dunderhead that I am - or, more forgivingly, Brit with scant feel for American party politics that I am - I'd no idea who Molly Ivins was before heading into Janice Engel's documentary Raise Hell. But here she is: nationally syndicated, Pulitzer Prize-winning political columnist, blowing out of Texas like a tornado, living (indeed, larger-than-life) proof that this state is, as one interviewee puts it, "America on steroids". Ivins was a big personality, evidently - bigger and more durable than most of the mediocrities she reported on. (You'd struggle to cast the lead in any Molly biopic, though a cross between Candice Bergen and the recently deceased Conchata Ferrell might have fit physically.) Ivins was a born storyteller, as becomes amply apparent from the chatshow appearances and book-circuit Q&As the film freely excerpts. The challenge Engel faces is to dig beyond the legend and bring us closer to the real Molly Ivins, even less well known as she may be on this side of the Atlantic. This she does, while also noting how this one woman's story closely intersects with the story of America in the second half of the twentieth century. Born into a segregated state, Ivins found her political voice amid the civil rights movement of the 1960s, then became one of many women to make a name for themselves professionally in the Seventies by elbowing their way into what had previously been boys' clubs. She was a progressive at heart, and was as pilloried for that as she was adored - but she tended to deliver those progressive sentiments with a six-pack of beer close at hand, and in a drawling Southern accent that led many to assume she was Republican by birth. In actual fact, Molly Ivins demonstrated even do-gooder Democrats sometimes like to take a drop.

Engel squeezes this life into that familiar 90-minute, TV-ready documentary template: her film is fast, fun and doesn't linger for long, either on the screen or in the imagination. Its chief selling-point is a lot of Molly herself: the well-polished anecdotes, the colourfully choice turns of phrase ("Texas politics is like Hungarian wine: it does not travel well"). Central to her journalism was a refusal to maintain any illusion with regard to elected officials, variously dismissed as "bozos" and "adolescent pissants"; of one councilman, she could be heard to remark "If his IQ slips any lower, we'll have to water him twice a day". Unsurprisingly, colleagues line up to pay fulsome tribute, from those who nurtured her talents back home to the more illustrious likes of Dan Rather and Rachel Maddow; Engel places Ivins firmly in a tradition of sceptical, often irreverent political scrutiny, which in turn answers the question of why anyone should revisit this story now. If Raise Hell has a serious purpose - if it's anything more than just a Molly Ivins greatest-hits collection - it's to position its subject in opposition to that latter-day client journalism that has wreaked so much damage on public discourse and wider Western democracy. Molly Ivins was too much her own gal to bow down or suck up for access, and too damn opinionated to both-sides a story; it made her a tricky employee, but it ensured that neither she nor her writing went soft on the system. Though of the Left, she damned Bill Clinton as "wishy-washy" (for which the New Statesman might substitute "neo-liberal"); the Engel line is that Ivins saw the rot creeping in at an early stage. (Is that why she upped her alcohol consumption in her later years? Looking back from 2020, you could hardly blame her.) The framing's more conventional than this subject would have likely allowed for, but Engel succeeds in making an engaging and entertaining case for Ivins as among the sharpest chroniclers of her era - and if you have a daughter looking to get into journalism, political or otherwise, Raise Hell might just play to her like the superhero movie of the year.

Raise Hell: The Life & Times of Molly Ivins opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Enter the void: "Antrum: The Deadliest Film Ever Made"

You may not have heard of Antrum, the Soviet film of 1977 about two youngsters who accidentally open up a portal to Hell while digging in the woods, but it trails quite the reputation: after sparking a fire at a Budapest cinema on first run, it then brought about a fatal stampede during a one-off engagement in San Francisco, and has been connected to the mysterious deaths of several festival programmers besides. The reason you haven't heard of it - the reason you won't find it in Halliwell's - is that it doesn't exist: it's a wholly fictitious artefact, conjured up by Canadian writer-directors David Amito and Michael Laicini for the purposes of a wannabe midnight movie that riffs on the legend of the "cursed film", as others have on cursed books or videotapes. The legend has been curated here with a measure of care. The Deadliest Film Ever Made opens with a mini-doc laying out the Antrum backstory, then - after a Gaspar Noe-like onscreen countdown offering concerned patrons the chance to leave the cinema (or, more likely in 2020, their own front room) - we get a look at the film itself, set out in artfully distressed images that gesture in the direction of late Tarkovsky, early Sokurov or Thatcher-era public information films, complete with cigarette burns to denote reel changes, and sporadic bouts of subliminal imagery à la The Exorcist. Here, alas, is where the project reveals its hand as obvious fakery.

The biggest giveaway is that, despite its grainy print quality, what's onscreen during the film-within-the-film never looks especially Slavic: its sundappled hills and capacious parking lots are undisguisably North American, while a Soviet film of '77 strikes me as unlikely to have "very special thanks" laid out in English credits. Juvenile leads Nicole Tompkins and Rowan Smyth are also far too blonde-haired and bright-eyed to convince as Eastern European moppets of the late 70s: if Amito and Laicini really wanted to dupe us, there needed to be fewer smoothies at craft services, and far more gruel. (Sometimes the Devil really is in the detail.) Enter into the spirit of it, and it gives up about as much fun as might be obtained this Hallowe'en from a Hasbro-brand ouija board: a half-hour's worth of thin, plasticky diversion, before the novelty wears off and everything turns deathly in the less critical sense. Even by the standards of late 70s art cinema, Amito and Laicini's pacing is trying, while any high-satanic seriousness is swiftly undermined by nerdy sniggering. The stopmotion squirrel is a nice touch; the dead moose-fucking less so. 24 hours after watching Antrum, I can report no deleterious effects, save a vague sense of an afternoon wasted, but then after the murder hornets and the deadly respiratory virus, so-so sleepover fare seems a long way down on the list of things we have to worry about right now.

Antrum: The Deadliest Film Ever Made opens at the Premiere Cinema in Romford this Friday, ahead of its DVD release on October 26.

Tuesday 20 October 2020

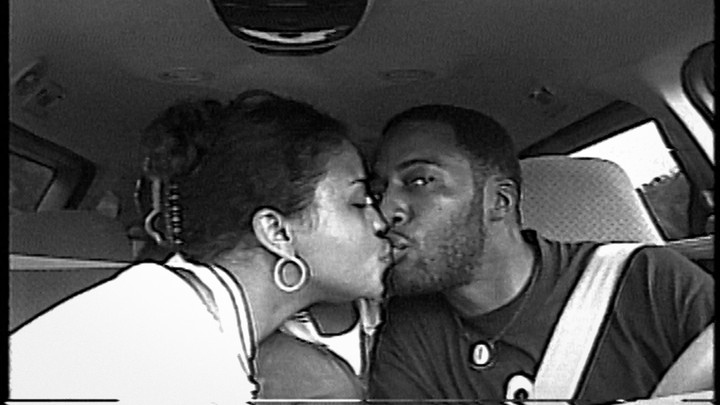

Clockwatchers: "Time"

Garrett Bradley's documentary Time opens with home-video footage of a young, heavily pregnant Black resident of New Orleans directly addressing the camera, and assuring the viewer that everything will turn out all right for her. Flashforward twenty years, and we find the same woman surrounded by kids and emboldened by the success bestowed upon her via a career as a motivational speaker and activist. The woman is Sibil Richardson, known professionally as Fox Rich, and to some degree, things clearly have turned out all right for her. Yet it's taken time, and what reality-TV contestants are fond of referring to as a journey, and some of that time has, in fact, been hard time: those home videos, we learn, were being recorded for the benefit of a husband, Rob, sentenced to 60 years behind bars for his part in an armed robbery. Sibil herself drove Rob there, and was sentenced to twelve years as an accessory; she's spent the years since her (early) release appealing her husband's sentence, which means navigating the byzantine corridors of the U.S. criminal justice system day after day. It's made for a long wait, all in all, and Bradley has ways of allowing us to feel the time. In a sharp sequence early on, we find Sibil phoning the County Clerk's office to hear Rob's latest appeal result, only to be put on hold; Bradley keeps filming, knowing full well the next time this woman hears a human voice, it will determine whether or not a wife can be reunited with her husband, boys with a father. If you find that extended pause excruciating, be thankful you're only eavesdropping.

So this is a film with time on its hands, to shape as it will. Some of Time's 81 minutes are spent watching those boys grow up, as Sibil herself has: Bradley shows us that the little cherubs in that video footage - to which the film returns from time to time, filling knowledge gaps, merging present and past - have, under their mother's eye, matured into nurturing, self-improving young gentlemen. (One's a dentist, another's making confident strides into the arena of student politics.) Mostly, Bradley's engaged in a process of quiet observation. She spies the everyday tenacity, patience and strength Sibil has to summon to get herself over the next round of challenges, but also the pronounced gap between his subject's polished public persona, schooling her fellow prison widows on how to tear down those walls ("I'm an abolitionist"), and how it is when it's just her and the camera, and she begins to let down her own defences. In these moments, the forceful influencer wielding a microphone like a horn of Jericho recedes, replaced by an ever so slightly tired middle-aged woman who can barely find the words she needs to express herself. There are points where it appears as if we've been brought this way to observe a personality split in two: Sibil is a mother and wife setting out into the world to make a life for herself and her boys, but she's also clearly left some part of herself behind bars with the man she loves. It's as though she had to invent the persona of Fox Rich, seen tersely repeating the mantra "success is the best revenge", to psych the very real, far more vulnerable Sibil Richardson up.

As a film, Time creeps up on you, and that's down to how much it wrings from scenes of humdrum ordinary life - from simply being around someone and keeping eyes and ears open. Bradley proves a master of the lingering close-up: she trains her camera on Sibil at work, church, graduation ceremonies or burning off some of her frustrations at the gym, assured that her careful framing - that choice sampling of camcorder footage to outline this woman's past - has clued us into what might be on her mind, or weighing on her shoulders. (And not just her mind and shoulders: another sequence finds her youngest boy at school, being lectured about the prison system. In this instance, a pupil might have more of note to say than his teacher.) The monochrome with which Bradley matches the home video gives Time an instantly poetic quality: it renders these lives timeless. Ignore the cellphones that pop into frame, and note the Christianity that serves as both a holdover and something to cling onto, and Bradley's film could be happening at just about any point in the past one hundred years. Which serves as its own damning indictment of the arthritic nature of American justice, so quick to condemn, so slow to forgive, or even to process: if the arc of history bends here, it does so almost imperceptibly. Still, sit tight, for there is the ending, which justifies all the waiting and fulfils the prophecy of those first frames, while leaving a stark caveat behind in its wake: that Sibil's is but one story among many, and that many of those won't have happy endings - indeed, they'll have no ending at all.

Time is now playing at the Everyman King's Cross in London, and streaming via Prime Video.