Indian cinema is, in fact, many regional cinemas in one – Hindi, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu and so on – each with their own stars and specialities. While the barrelling action of one current hit, Jawan, prompted breathless responses across northern India, many southerners sniffed, claiming it was but a pricey impersonation of those rowdy crowd-pleasers their industries have turned out for decades.

Such films remain swirling melting pots of fisticuffs, gunplay, romance and song, earning themselves the (homegrown) sobriquet “masala movies”. Long before old Bombay morphed into latter-day Mumbai, this cinema contained multitudes, setting eyes to widen and minds to boggle, and leaving casual onlookers – even some of our shrewdest critics – feeling overwhelmed.

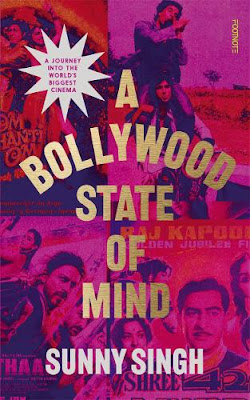

Expert guidance is required, then, and with her new book, Sunny Singh, well-travelled novelist and professor of creative writing at London Metropolitan University, makes a true heroine’s entrance. Part-history, part-memoir, A Bollywood State of Mind details how Singh caught the cinephile bug as a diplomat’s daughter shifting around India, her alienation from Hollywood’s prosaic, single-track narratives, and her inability to escape the movies and songs of her homeland, wherever life carried her.

The essence and art of masala, we learn, is a balancing act, “a combination of transitory moods and permanent internal states”. If so, A Bollywood State of Mind might be claimed as a masala book, its prose alternating between professorial wisdom and something dreamier besides.

Uppermost in the mix is the history, spanning from 1913’s Raja Harishchandra, the foundational silent regarded as the first Indian feature, to January’s Pathaan, blockbusting vehicle for reigning Bollywood king Shah Rukh Khan. Here, Singh identifies key stars and directors, familiar archetypes and tropes, and discusses how and where cinema intersected with the wider Indian project: the push for self-determination during colonial rule, the Modi-backed resurgence of Hindu nationalism.

One idiosyncrasy is the near-sacred text the author clings to as an interpretative secret weapon: the Natyashastra, an ancient Sanskrit encyclopaedia of the arts which sought to elevate creative endeavour to the status of the divine. (It makes Stanislavski and Brecht’s writings on theatre seem like child’s play.)

Expanded from the author’s doctoral thesis, this reframing of movie history is where the book flirts openly with an academic register. The Natyashastra’s dramatic pointers reminded me of film theorist Christian Metz’s narrative paradigms, bane of many an undergraduate.

Yet, in Singh’s hands, they point towards a fuller and deeper understanding of Bollywood norms: the unapologetic repurposing of what some would dismiss as cliché, for example, or the recurring reincarnation theme. They even provide spiritual reasons for the intervals that still come as standard with Indian cinema.

Whenever the book leans toward the arcane, Singh shifts approach and demonstrates that this cinema’s singular power is more than typically bound up with emotion and memory. It’s just that her memories have been rescaled by the movies themselves. Even her footnotes suggest frames from some thunderous widescreen melodrama: a grandmother remembers fleeing an earthquake “clutching her infant sister and a cage with her parrot… as the ground around her opened up in deep cracks”.

While disconcerting at first, Singh argues, masala cinema’s extremes of emotional colour, and sudden tonal and perspectival shifts ultimately provide a fine preparation for life’s vagaries: the highs, the lows, the sudden outbreaks of frenzied dancing. What’s more, they function wherever you are. A local whom Singh encounters on a research trip to Senegal bursts into Hindi song, and confesses Indian films “taught me a different way to see”.

If recent admission numbers are anything to go by, Western cinemagoers would seem to agree: the (joyous) romcom Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani held down a screen at my local Odeon for nine weeks – while more floundering Hollywood options came and went. Arriving at a moment when streaming services are further lowering the barriers that have traditionally separated us from adjacent cinemas and cultures, Singh’s book serves as both a greeting party and a gentle re-emphasis.

In her introduction, Singh writes of the goals she set her younger self: “I would study and learn, and develop the language I needed to share the films I have loved all my life. And I would find ways to share that love with my colleagues, friends and even strangers, in words they already knew. Gradually, I was sure, they’d learn my words as well as I had learnt theirs so we could sit together before a screen to watch, and to love, the same films.” Her adult self now bestows that language on us – and a watchlist to keep Netflix devotees going for several lifetimes.

A Bollywood State of Mind (Footnote Press, Hardback, 272pp, £20) is published October 19.

Your blog is amazing! If you want more Bollywood updates, follow moviemagicgram

ReplyDelete