These are, as I've mentioned before, tough times for tough men. Faced with the done-for-real stuntwork of Tony Jaa (Ong-Bak, The Warrior King) and the free-running trend showcased by films as diverse as District 13, Casino Royale and Breaking and Entering, our movies' erstwhile action heroes have reverted to former glories, if not vanished from sight altogether. Van Damme and Seagal have long since disappeared from cinema screens; before he moseyed away into politics, Arnold Schwarzenegger had to make a third Terminator to reconnect with an audience. And though he's managed to reposition himself as an iconic character actor for independent minded directors (via Sin City and Fast Food Nation), Bruce Willis's last stab at playing the action hero, last year's 16 Blocks, essentially replayed key scenes from Die Hard with a Vengeance - so successfully, in fact, that it earned a greenlight for a Die Hard 4. For Sylvester Stallone, it's hard to know what must have been the greater indignity: being paraded around at an Everton game, signing on for a fourth Rambo film, or reaching a point in his career where a sixth Rocky film seems like the only way forward.

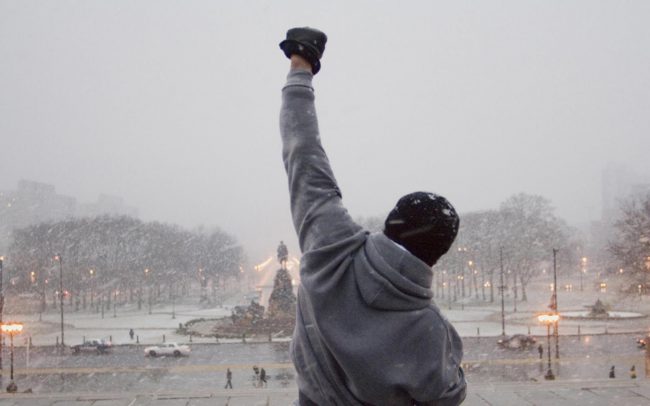

Rocky Balboa has been conceived as a nostalgia exercise: it opens with a Frank Stallone song ("Take You Back"), Rocky's first line is "Time goes by so fast", and its early scenes are linked by a series of fades that form the editorial equivalent of an addled boxer's memory lapses. That the film succeeds as Saturday night entertainment is down to how self-aware it is about this. Stallone, here taking a writer-director-star credit, knows what made the first Rocky work so well (if it ain't gashed, don't stitch it), and surely senses time is running out for him to add to his legacy. Rocky is now found stumbling around his tumbledown Philly neighborhood, boring the patrons of his restaurant ("Adrian's", poignantly) with anecdotes of better days. He's shaken out of this funk by a hesitant relationship with a similarly lived-in bartender, Geraldine Hughes' Marie, then by long-suffering trainer Paulie (Burt Young)'s talk of what he calls "a cartoon fight" - a computer simulation staged by a sports network that has Rocky beat present champ Mason "The Line" Dixon (Antonio Tarver). An in-person rematch is mooted, hardly a fair fight - it's like pitting Amir Khan against Muhammad Ali - but then, as the movie suggests, the fight game isn't what it used to be.

Dixon's handlers are portrayed as greedy goons, who accept the challenge despite the fact their man has nothing to gain from it but wealth; there's an obvious dichotomy between these wraiths, who walk into the arena all but rubbing their hands ("Know how much money there is in this?"), and Stallone's Rocky, whose entourage includes a God-fearing restaurant regular, his son Robert (Milo Ventimiglia) and the spirit of Adrian, and whose first response to the cavernous Las Vegas venue of the Dixon bout is decidedly blue-collar ("Imagine cleaning this place"). Rocky Balboa really does transport you somewhere, even if it is just back to the Seventies, when Stallone was considered, in all seriousness, a triple threat. Though it seems as though whole characters (such as Marie's briefly seen son), scenes and much of the climactic bout have hit the canvas in the edit suite, Stallone's direction, particularly in the early stretch, is marked by crisp street-level photography of real-world locations. And as screenwriter, he's done a solid job of paring the storyline back to the virtues of the first Rocky: this is old-fashioned storytelling, albeit with flurries of knowing dialogue, jabs of self-recognition. "Yesterday wasn't so great," Paulie insists, trying to shake his fighter from his nostalgic funk. "It was to me!," yelps Rocky, or maybe Stallone. When Marie tells our hero "face it, this is who you are and this is how you'll always be", it's not the only line that rings bells in the context of the star's own career.

Above all else, Rocky Balboa reminds us of the strengths of Stallone the actor, here stubbornly - heroically - refusing to let his keynote character slip into self-parody. Rocky's garbled yet heartfelt address to a boxing board understandably reluctant to grant this oldtimer a new licence, and one later, after-hours speech on the street to his son are masterclasses in acting inarticulacy, a skill at least as valuable as mastering iambic pentameter. The new film's appeal resides in such moments, where we catch the character just trying to function; they're reminders Rocky always was as much boxer-dog as boxer-man, a dumb mutt whose best conversations have all been with fellow strays. Adrian worked in a pet store, you'll remember; here, we get a midfilm trip to the dog pound, and you half-wonder whether Rocky's here to adopt or be adopted. It could suffer commercially from telling a comparable story to last week's The Pursuit of Happyness, a phrase that gets an impromptu namecheck when Rocky cites the Bill of Rights to that boxing commission; as its underperformance in the U.S. over Christmas suggests, the film is unlikely to bring in the teenagers for whom Stallone exists in the cretaceous period, if at all. Yet when Bill Conti's Rocky theme "Gonna Fly Now" kicks in over shots of the star downing raw eggs, anyone over a certain age will almost certainly be basking in an appreciably warm glow: what's being offered here finally isn't just nostalgia, but the oddly touching sight of a character and a performer still struggling to express themselves the only way they know how.

(January 2007)

Rocky Balboa returns to cinemas nationwide, along with Rocky and its immediate sequels, this coming Friday.

No comments:

Post a Comment