Monday, 17 April 2017

Soft diplomacy: "Letters from Baghdad"

Letters from Baghdad is an excavation of sorts: an attempt to return to plain sight a figure who, while not necessarily forgotten, may have become obscured over the past century. That figure is Gertrude Bell, adventurer, mapmaker and contemporary of T.E. Lawrence, and we know full well how the cinema's idea of British involvement in the Middle East has been shaped by that very white male romantic. Here, then, is a counterhistory, striving to pin down a woman who occupied much of the same space as Lawrence, yet was more often than not behind the camera rather than before it, and thus never appeared on David Lean's radar. The directing partnership of Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum set out their case in much the same fashion as 2014's The Decent One, Vanessa Lapa's documentary on Heinrich Himmler, layering readings of their subject's diaries and correspondence over photographs and archive footage. Thus are we carried from an idyllic Home Counties upbringing to fin-de-siècle Oxford, thence a series of expeditions into the wider outposts of Empire: one moment Bell finds herself in newly liberated Tehran, the next this professional migrant is making herself entirely at home in Syria, in a way that can only seem poignant indeed to onlookers in the year 2017. Here is a woman determined to go her own way.

It makes sense that the directors should have asked Tilda Swinton to provide the contours of Bell's voice in adulthood: as we learn more of her assignments for the Foreign Office, she emerges as a restless, idiosyncratic soul, not terribly interested in settling down - Lawrence, we learn, described her as "not like a woman" - yet bound by a sincere wonder at and love of the region to which she was dispatched. Her personality, arguably, registers rather more forcefully than the film overall, which finds a groove early on and never deviates from it. The Himmler doc deployed its handwritten notes to investigate the discrepancy between its subject's reputation as an architect of evil and the banal reality of a petty-minded bureaucrat permitted to give free rein to his prejudices. Clearly, there is no comparable discrepancy here, though Bell's correspondence grants us an inside line on her experiences, a sense of the high esteem she was held in by her employers and many of her contemporaries, and of the huffy-stuffy patrician forces whose clumsy attempts to divide up the ground she was standing on resulted in several still ongoing conflicts in the Middle East.

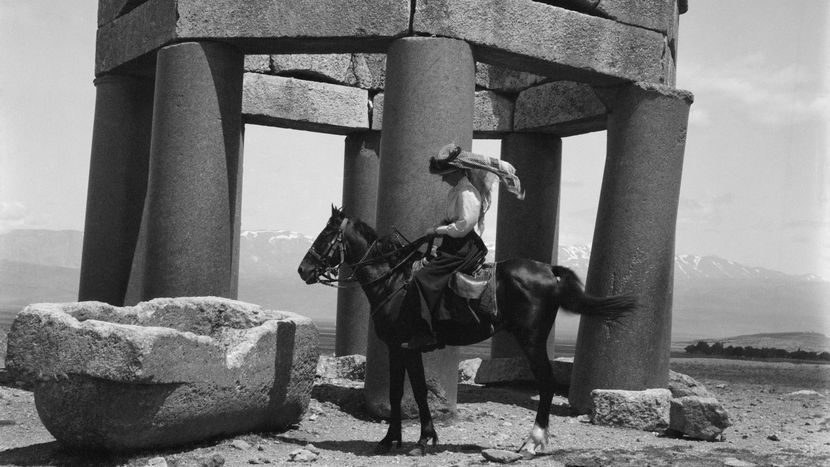

Set side-by-side without any further context or deeper analysis, however, all they amount to is a naggingly flat chronology: a series of wish-you-were-heres, pins on a map, names, dates and times - which, for all Krayenbühl and Oelbaum's evident facility and dexterity with archive images, never really come to life as compelling cinema. "It's strange to be treating all these tragic places as stages in a journey," Bell confesses in one of her missives, suggesting a degree of self-awareness that exists just beyond the film's reach. Every now and again, something pops up to catch and hold the eye: you can't help but struck by the few surviving photographs of Bell, where she cuts a spectral, Zelig-like presence - as though she wasn't meant to be there, as doubtless some in high office would have insisted, or simply as if she didn't want to impose herself upon the environment in the same way the men of the party clearly did. Yet almost the entirety of the second half is turned over to the kind of diplomatic minutiae that, while historically revealing, makes for a perilously dry sit. For all that Krayenbühl and Oelbaum have succeeded in bringing Bell back to the surface, they immediately entomb her in what feels often like an exhibition projected vertically - and one that allows scant room for the viewer's imagination to truly roam.

Letters from Baghdad opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment