The success of Netflix's The Last Dance has reawakened an interest in the life, career and endorsements of basketball superstar Michael Jordan: new doc One Man and His Shoes is opening in the UK a week before the revival of a 2000 IMAX special going under the none-more-Nineties title of Michael Jordan: To The Max. (We also have that Space Jam sequel awaiting us next summer.) Yemi Bamiro's film has one very specific aspect of this legend in its sights and on its feet: it's a history of those Nike trainers to which Jordan lent his name. Yet Bamiro comes this way with a fair bit on his mind, which may be why the results feel so scattered. These 83 minutes aren't merely about running shoes, but how Air Jordans sat at the centre of a nexus of race, celebrity, politics, corporate branding and popular culture. You'll need some tolerance for footage of CEOs and agents sitting around well-furnished homes talking with pride about the deals they struck to ensure a young athlete was handed staggering sums in return for wearing freebie trainers - it's predominantly a money story, and one that has to position Nike as a plucky underdog in order to sketch the narrative arc it wants for itself. Despite Will Newell's jazzy graphic design, much of that positioning is achieved within a conventional talking-heads format. Yet it has a secret weapon in Bamiro's confident marshalling of the ephemera these deals generated, the print ads and promo spots that did almost as much as Jordan himself did on court to secure his public image. It means to sell you on a non-essential item that would swallow your monthly salary and be obsolete within the year, but the double-page image of Jordan mid-air and mid-dunk remains an eye-catcher; and "Michael Jordan 1, Isaac Newton 0" is tremendous copywriting, wherever you're coming from. And that's before Bamiro works in those zippy, Spike Lee-directed campaigns by which Nike started to run rings around their sporting rivals, with their lame "rapping athlete" spots. (It's a bit like discovering Public Enemy on the same chart as the "Anfield Rap".) Still, from an early stage, there are tensions beneath the film's surface that Bamiro never fully resolves.

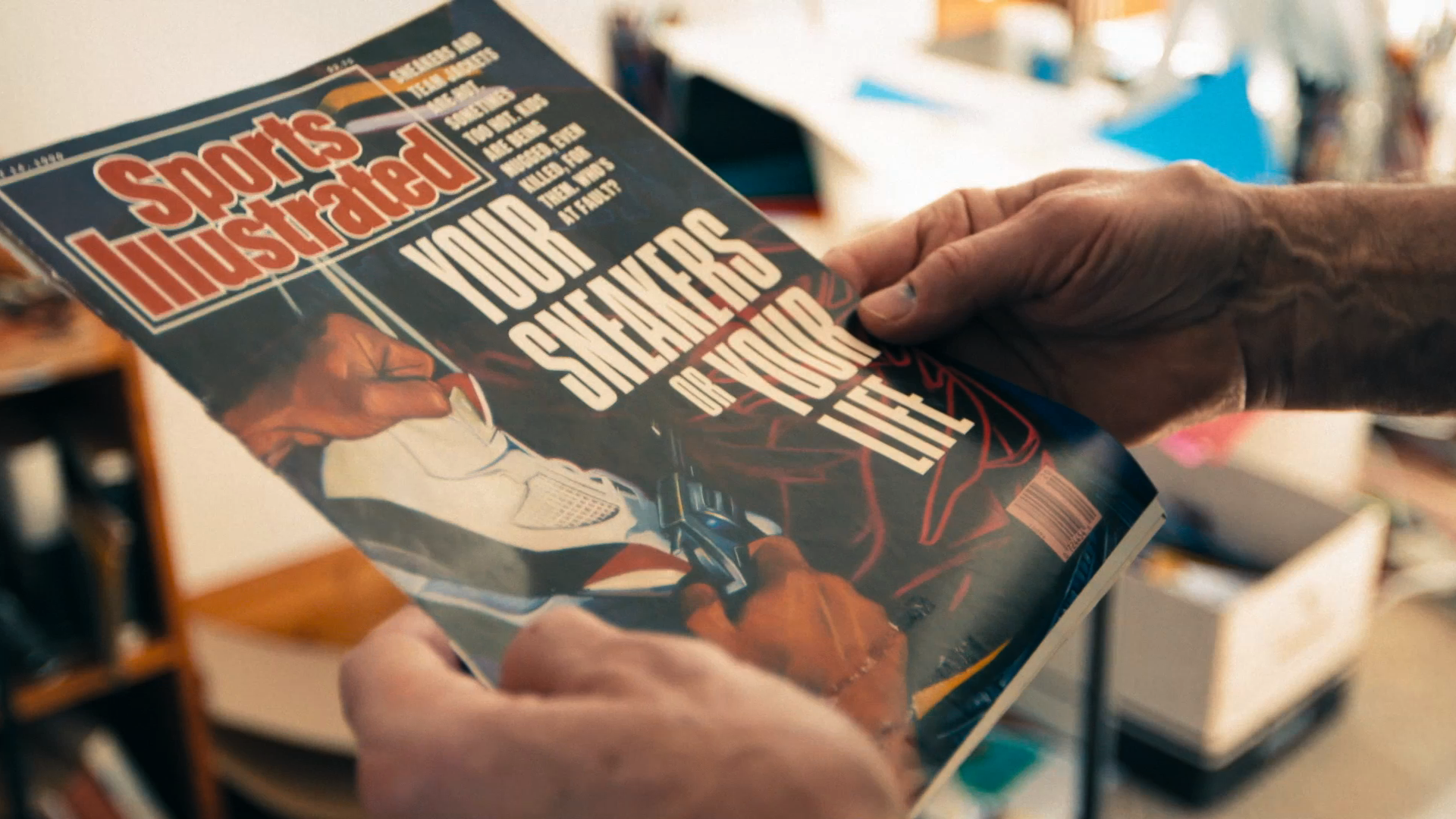

Granted, they were there in the original story, which was that of corporate America making one young Black man a star, and bestowing unimaginable riches upon him; riches that were solicited, in great part, from impoverished inner-city children for whom a $180 pair of sneakers became an exit strategy, a status symbol, and - in certain cases, touched on late in Bamiro's film - something to die for. What was being sold with that Jumpman logo was an image of Black strength, beauty and success. (As those Lee ads regularly wondered: "Is it the shoes?") How that image squared with American reality is what matters, and it's here you sense Bamiro, making his feature documentary debut, getting muddled. He's outright distracted in those segments involving Air Jordan hoarders, a jolly quirk that makes for a crunching gear change when the film then confronts us with images of youngsters in deprived areas being mugged and killed for their footwear. Now we learn that Nike knowingly withheld from the supply chain so as to ramp up demand for their product; now we hear the lawyer for one grieving family denounce those ads the documentary has previously taken so much pleasure in as the propaganda of a corporation valuing profit over human life. It's either a structuring issue, or a failure of editorial nerve: to make the leap from fanboy to journalist, Bamiro really needed to take the footage he shot at Houston gravesides to the mansions of the suits he chuckles along with early on - or, indeed, to Jordan, a no-show who continues to cash the cheques - and to ask these powerbrokers how much responsibility they're prepared to take for Nike's moral failures. It's an angrier film than it lets on, I think; I wonder whether Bamiro was advised to make nice for much of it. He gets in plenty of coverage, but at some point he needed a pivot worthy of Jordan himself; in the absence of that, we're left with a film whose two halves don't quite fit, like mismatched pumps on the shelf of a Foot Locker backroom. We can still admire the design, but they make for uncomfortable travel.

One Man and His Shoes is now playing in selected cinemas, and streaming via Prime Video, Curzon Home Cinema and the BFI Player.

No comments:

Post a Comment