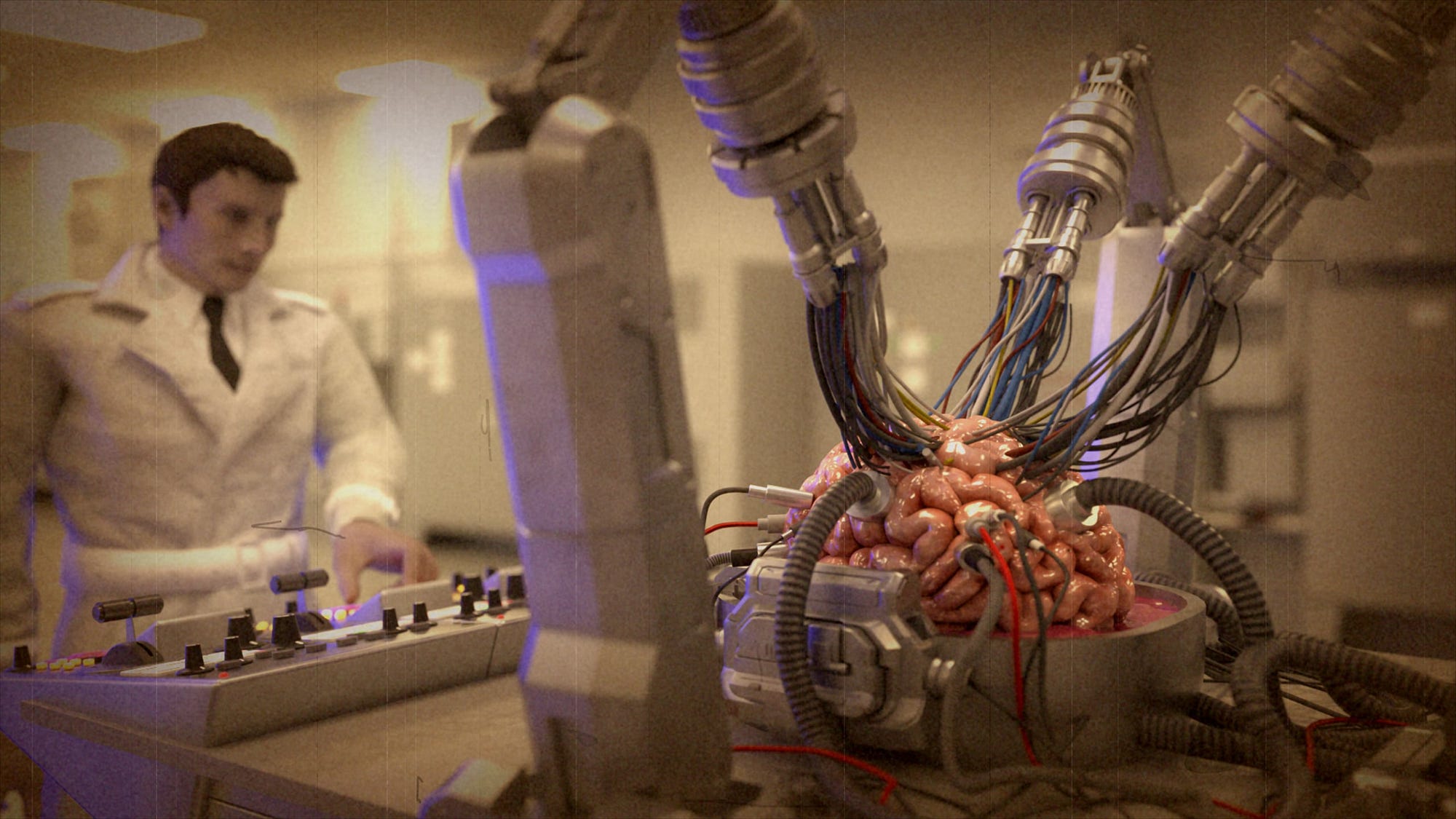

The documentarist Rodney Ascher is carving out a space for himself somewhere to the right of Adam Curtis, to the left of QAnon, and a level or two up from certain YouTube creators. In the byzantine corridors of cinema, he's set up shop in a small office way down the end, next to the heating outlet; it has no windows, and there's always a funny smell in there. Ascher first emerged from this curious space clutching Room 237, a tatty, overstretched round-up of the manic online speculation that maintains Stanley Kubrick's The Shining contains nothing less than the secrets of the universe itself. That was self-evidently fanboy work, more enthusiastic than it was journalistically rigorous; my feeling was that if Ascher started repeating these theories to you in person at a bar or bus stop, you'd run a clear half-mile just to shake the guy off. His latest A Glitch in the Matrix uses the Wachowskis' newly canonical sci-fi blockbuster as a springboard to discuss simulation theory - the idea, central to that Keanu vehicle, that we're all now living in a computer program being run by some advanced civilisation. (On good days, it's The Sims. On bad days, Grand Theft Auto.) The new film leans even further into the nerdiness than its predecessor. It's narrated by a robot (female, of course, for sexy times). And the bulk of its almost exclusively male interviewees appear on their webcams as extravagantly animated computer avatars. This, I think, is meant to bolster the argument that we're all now more pixel than person - an image on a screen, and not just our own screens. Yet coupled with their testimony, it also has the secondary effect of implying that simulation theory - not unlike so much of the modern world's suckery - is an idea people get into when they have the time on their hands that follows from not getting laid enough. Presumably not getting laid, in these theorists' eyes, has nothing to do with personality defects and everything to do with someone on a higher plane not pushing the right combination of joypad buttons.

Look, I get why simulation theory might be reassuring: it suggests that none of what happens down here at the game level is our responsibility, or our fault. Yet - beyond the fact it depends on us taking moneyed cranks like Elon Musk and other Men on the Internet seriously - it also (as the sole female interviewee points out) lets us entirely off the hook as individuals and citizens: again, none of what happens - up to and including the possible annihilation of the universe, shrugged off onto the cosmic equivalent of the careless Tamagotchi owner - is our responsibility, or our fault. It's a get-out clause for late capitalist shut-ins, the philosophical equivalent of the mother's note that spares you the brutalities of gym class. Ascher can't make much of a case for it, whatever it represents. He's inherited that Curtis-y tic of mashing up wildly disparate sources and stories (random news footage, classical and historical precedents, clips from Netflixable sci-fi titles), stepping back with a wobbly-voiced cry of "ta-da!", and assuming that's enough to make any given point. His stronger material here - like the first-person testimony of Matrix fanatic Joshua Cooke, driven to gun down his parents to settle his own argument about simulation theory - just gets buried beneath reels of babble and gabble from men who open their mouths and yap without filter. (One enthusiast has barely introduced himself before letting slip he has Crohn's disease. Does he really think any overlord would go to the trouble of programming that?) By the time we get onto the Mandela Effect, officially the dullest, most done-to-death concept in Western pop science - yes, special one, you misremembered something! Have a biscuit you probably can't recall the name of, either! - I was actively bashing my head against my laptop, and it was definitely me doing that, not Gargatron F from the Xpialidocious galaxy. I mean, if you need more speculation and noise in your life at this point in the 21st century, have at it, but you surely have to be slightly cracked - possibly even halfway towards murdering loved ones - to give this much credence. Can't we ask Gargatron to turn the volume down on this universe occasionally?

A Glitch in the Matrix will be available to stream tomorrow via Prime Video, Curzon Home Cinema and Dogwoof on Demand.

No comments:

Post a Comment