Tuesday 31 July 2012

Three chairs for the office: "Eames: The Architect and the Painter"

It may be a damning indictment of the artless and unstylish life I've so far lived, but I honestly hadn't heard of Charles and Ray Eames, the husband-and-wife team who revolutionised the design of America in the years after World War II, before I sat down to watch Jason Cohn and Bill Jersey's documentary Eames: The Architect and the Painter. The Eameses had some influence on the look of TV's Mad Men, which - coupled with the current boom in counterprogramming - gives some clue as to why this small-screen doc, from the same American Masters strand as the recent Woody Allen: a Documentary, is receiving a UK theatrical outing.

The Eames Office, we learn, was distinguished in two respects. It was multi-disciplinary, believing art, architecture, film and photography to be part of the same creative urge, to be followed wherever it may lead. Eames himself was as likely to turn his attentions to planning a dream home as he was to turning out a cutesy stopmotion animation, an educational film for one of his corporate patrons, or one of the plywood chairs with which he first made his name and fortune. Secondly, this was a broadly egalitarian enterprise, staffed by collaborators committed to producing - in the words of the Eames office motto - "the best for the most, for the least", and in doing so benefitting from the consumer boom of the late 1940s and 50s.

As a couple, the Eameses divided along gender lines: Charles the stiff, analytical engineer and architect, forever tinkering with details and blueprints, while Ray - a painter by trade - brought colour and flexibility to the pair's projects. Their marriage is as much a part of the legend as the Eames Office itself, or the fabled Eames House: how it mixed and matched different skillsets, devoted to the notion of "learning through doing". Just as the first Eames chair came about through a happy accident, so Charles met Ray while with his first wife, and this do-over would change (at least some small part of) the world. Yet Charles's open-mindedness almost put an end to the marriage, and dented his professional reputation when his cluttered Bicentennial exhibition on the lives of Franklin and Jefferson opened at the Met in 1976.

All of this is interesting enough, but at the end of the day, we're still being asked to coo at tables, chairs and corporate commissions, which may only make Eames a must-see for those who still have the money (and inclination) to subscribe to *Wallpaper magazine. Still, you get a parade of experts - including Paul Schrader, who specialised, as a critic, on Eames's filmed output - between the evocative archive footage, which is rich in the saturated colours of an America on the brink of going pop, and Cohn and Jersey find respectful ways of integrating criticism of the Eameses' scattershot, artsy-fartsy approach. Take the testimony of the architect who, having been invited to the Eames House for dinner, was presented with three bowls of flowers by way of "visual dessert": "I was really fucked off. I hadn't eaten much that day."

Eames: The Architect and the Painter opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Monday 30 July 2012

Turnarounds: "Undefeated"

This year's Academy Award winner for Best Documentary, Undefeated, is one straight out of the triumph-over-adversity file, seemingly designed to pick up where the season finale of TV's Friday Night Lights left off. It opens with shots of dilapidated and abandoned North Memphis houses, and does rather give the endgame away the moment the title appears on screen; so predictable is it in its trajectory from the first point to the last that, from this distance, it's hard not to think it was Harvey - and the substantial marketing clout of the über-producer's Weinstein Company - what won it the Oscar.

Directors Dan Lindsay and T.J. Martin have filmed a season in the life of the Manassas Tigers, a Tennessee high-school football team who at first seem ironically named - because they possess next to no bite on the field whatsoever, and can most often be seen rolling over and presenting their bellies for the opposition to tickle. The Tigers' long-suffering volunteer coach is Bill Courtney, and whatever grip Undefeated holds depends more or less entirely on that particular V-word: we're being encouraged to marvel that this portly blond familyman would willingly assume the burden of turning round the fortunes of this losing enterprise, and man-manage mere boys, some of whom have accrued criminal records in their short time on this planet, many of whom slouch and shrug and struggle to keep their own pants up.

Away from the playing field, Courtney runs a local hardwood business, and we spot the parallels all too quickly. This is a born craftsman, who's set himself to taking the rough edges off the raw materials presented to him, constantly having to refine and smooth his methods. Courtney prefers a close-up, hands-on style of management: he's a hugger, going after players who've stormed out of team meetings to remind them of their place in his gameplan, and at one point driving his van up on the kerb in an attempt to keep up with the team's star tearaway Chavis Daniels.

For a while, the film delivers generic pleasures. We wonder just how bad this season is going to get before it inevitably gets better, and the answer turns out to be: pretty bad. After an early tonking on the pitch, two Tigers take a swipe at one another in a post-match briefing; one away game ends with a police cordon encouraging Courtney and his charges to get right back on their bus, rather than risk an after-game dust-up with their enraged opponents and their supporters; another game ends with the team's star player being ruled out with an injury for the remainder of the season. Then it's just a matter of waiting for the turnaround.

The kids - daffy enough to ask "Is that my brain?" upon being shown a C-scan of their own injured knee - keep Undefeated from becoming entirely predictable; the transformation of Chavis from glowering adolescent skulker to college-bound figurehead is cheering, and can be learnt from. But Lindsay and Martin can't overturn a crippling feeling of gridiron (and documentary) by numbers. Within a narrative framework familiar through everything from Remember the Titans to The Replacements, we get the obligatory prayers and pep talks, played out over ambient shots of floodlights; spitballed homilies on the importance of family, education and doing the right thing; and a final round of hugs and tears that plays as as much Oscar bait as anything in War Horse. In the unlikely event you haven't seen this story told before, you could always skip Undefeated and hold out for the feature some inspiration-starved executive is presumably prepping to make from it, doubtless with Philip Seymour Hoffman in the Courtney role.

Undefeated opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Silly games: "Truth or Dare"

I've found the following a good general rule in life: should the nerd you've publicly humiliated at a party invite you to his isolated country cottage several months later for fun and frolics, it is - however much alcoholic and narcotic refreshment or barely legal tail is rumoured to be on offer - always going to be best to claim you're washing your hair that night. This, of course, doesn't enter into the pretty little heads of the rich kids in the new British horror flick Truth or Dare, who duly set out for the advertised good time, only to be confronted with the consequences of their actions when the ex-squaddie brother of the nerd in question holds them all hostage and demands to know why they did what they did.

Robert Heath's film operates on or about the same level as last year's fly-by-night quickie Demons Never Die. It has a watchable young cast, and has been staged with a basic competency, which isn't always a given at this level of filmmaking; Heath fares marginally better with six people in a room than he did with the three people in a room of his debut, the lifeless theatrical adaptation SUS. Still, it gets static and repetitious, the bottlespinning encoded in the title cueing a limited set of responses: the tortured weep and wail, while their captor has but the one torture method (battery acid) at his disposal, giving this very 15-rated entry the feel of a rather toothless Saw.

It's not an especially good sign that Heath feels the need to throw on rent-a-geezer Jason Maza around the hour mark to freshen matters up, but the bigger problem lies at the conceptual level, with a script that asks us to side with - or even remotely care about - a set of squealing, squabbling, varyingly sympathetic Young Conservatives over a victim of bullying and somebody who fought for their country. I don't suppose anyone involved in Truth or Dare had the slightest intention of making a statement - not when they could be making money, or a name for themselves (and good luck with that, fellas) - but I can't help but think this is what happens to a film industry when we elect the likes of Dave "Dave" Cameron to office.

Truth or Dare opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Sunday 29 July 2012

1,001 Films: "Pickup on South Street" (1953)

From its brilliantly self-reflexive opening sequence - a kerfuffle amongst strangers on a packed subway train ("What just happened?" "I'm not sure yet") - to the staggeringly brutal fist-fights of its final reel, Pickup on South Street forms an early example of Sam Fuller's genius with thick-eared, hard-boiled scenarios. Richard Widmark's pickpocket Skip McCoy swipes a purse containing a secret formula, and soon finds himself pursued by parties from both sides of the sting operation he's stumbled into: the crooks trying to flog the formula to the highest bidder, and the cops trying to prevent such a secret from falling into enemy hands. Widmark resolves to do nothing, except to hang onto his suddenly priceless booty and taunt anyone who has the misfortune to step into his atmospheric dockside haunt. Minor characters include an eccentric bag lady (specialty: hooky ties) whom the police bring in as an informant, and a fat heavy using chopsticks to stuff dollar bills in his pockets. Everybody sweats a lot, and no-one's especially likable: in the space where audience sympathies would usually go, we get a) Widmark as an anti-hero who's slightly preferable to everyone else because he realises the microfiche in his possession has worth beyond the financial, b) an understanding of the fears that powered the Atomic Age ("You'll be as guilty as those traitors who gave Stalin the A-bomb"), and c) an urgent sense that the heat is very definitely on.

Pickup on South Street is available on DVD through Optimum Home Releasing.

Saturday 28 July 2012

1,001 Films: "Madame De..." (1953)

Max Ophüls' Madame de... is one of those rare films in which the focus of attention isn't a human being, but an inanimate object: in this case, a pair of earrings given to the title character by her husband, sold for hard cash, and subsequently passed around the world while three of their first four owners - general Charles Boyer, baron Vittorio de Sica and Danielle Darrieux as the woman who comes between them - themselves circle around one another. Restlessness, rather than constancy, guides the storytelling here: the film doesn't have a plot so much as a series of variably tiny indiscretions stitched together with the grace and elegance of an aristocrat's silk glove. The central seduction sequence - involving a married woman, egads - is presented as one long, continuous waltz that compresses several other extracurricular trysts into magical cinema. It's suitably opulent - Ophülent, even - but never content merely to revel in its opulence; it is, instead, a film of great spirit in which characters dwarfed by the grandeur of their surroundings, and by the forces of fate and destiny pitted against them, attempt to fight back, make their presence felt and their hearts, long muffled by layers of immaculate tailoring and noble conditioning, sing once more. Ophüls knows exactly where he stands, treating the earrings as the trinkets they are, and giving the wittiest, most telling lines to the musicians, ushers, footservants and servants watching the whole damn merry-go-round glide by.

Madame de... is available on DVD through Second Sight.

Friday 27 July 2012

For what it's worth...

Top Ten Films at the UK Box Office

for the weekend of July 20-22, 2012:

1 (new) The Dark Knight Rises (12A) ***

2 (1) Ice Age 4: Continental Drift (U)

3 (2) The Amazing Spider-Man (12A) ***

4 (3) Magic Mike (15) **

5 (6) The Five-Year Engagement (15) **

6 (5) Cocktail (12A) **

7 (4) Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (15) ***

8 (7) Men in Black 3 (12A) **

9 (8) Prometheus (15) ****

10 (9) Katy Perry: Part of Me (PG)

(source: BFI)

My top five:

1. The Red Desert

4. Salute

5. Ted

Top Ten DVD rentals:

1 (2) The Descendants (15) ***

2 (1) The Woman in Black (12) ***

3 (3) Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (12) *

4 (new) Chronicle (15) ****

5 (new) Young Adult (15) ***

6 (9) The Iron Lady (12) **

7 (new) Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance (12)

8 (8) Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol (12) ***

9 (10) The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (18) **

10 (5) The Muppets (U) ***

(source: lovefilm.com)

My top five:

3. Wild Bill

4. Being Elmo

5. The Raven

Top five films on terrestrial TV this week:

1. The Fugitive [above] (Tuesday, ITV1, 10.35pm)

2. Before Sunset (Wednesday, ITV1, 3am)

3. Exit Through the Gift Shop (Friday, C4, 12.15am)

4. The Man From Laramie (Sunday, BBC2, 1.15pm)

5. Once Upon a Time in Mexico (Monday, five, 11pm)

On the verge: "Woman in a Dressing Gown"

Written by Ted Willis (best known for The Blue Lamp) and directed by J. Lee Thompson (better remembered for Ice Cold in Alex and the original Cape Fear), the unusual 1957 offering Woman in a Dressing Gown now looks like both a women's picture in the conventional sense and a deconstruction of same. At its centre is a character who couldn't be further away from the domestic goddesses fetishised by countless 50s movies and newsreels. We first see Amy (Yvonne Mitchell), bedraggled wife and mother, as she attempts to rouse the inhabitants of the small council flat she calls home: like a whirlwind, she turns up the radio too loud, burns the toast, and proceeds utterly unfazed by the stacks of unattended washing, ironing and sewing tossed around her. Her teenage son (Andrew Ray) is bemused by mum's continual inability to stay on top of things, or indeed to get herself dressed properly: "You work like a horse, but you never seem to get anywhere."

Worse, though, is to follow. When Amy's husband Jim (Anthony Quayle) leaves the flat that morning, it's to see his mistress Georgie (Sylvia Syms). Gorgeous in a very English way, and the model of elegant, demure femininity, Georgie is only too happy to put the kettle and a Sunday roast on for her man; the contrast with Amy, observed singing tunelessly along to a crass ditty with her friends in the pub, is a marked one. Willis and Thompson were playing a dangerous game here: the framing of their film is such that Woman in a Dressing Gown risks misinterpretation as a cautionary tale, insisting that divorce is just what happens, ladies, if you don't put the necessary effort in around the house. Yet the feel of the film, on a scene-by-scene basis, is of something looser and New Wave-y, French as well as British. Mitchell, wearing her tousled hair as a defiant signifier, gives one of the great scatterbrained performances of British cinema - a turn that begins as pure jazz, yet lapses into the tired mania of a woman desperate to keep up everybody else's appearances at the expense of her own. And Quayle, too, makes perhaps surprisingly sympathetic a decent man - a gentleman, in most respects - who's somehow found himself trapped by the life of domesticity.

Thompson shoots the little boxes these characters inhabit as though they were prison cells, with sheets hanging from the rafters and iron bars on the windows; Amy and Jim don't have room to breathe, let alone think, and we're reminded that Room at the Top and Cathy Come Home were only a couple of years away. Woman in a Dressing Gown remains just a little too discreet to be truly angry or radical about the domestic environment, in the way these films, or its later French equivalents Jeanne Dielman... or Two or Three Things I Know About Her would be - it climaxes in some very familiar arguments around the kitchen sink, resolved over cups of tea - but this remains an interesting, noteworthy rediscovery, telling us as it does something of what it might well have been to be a woman in the Britain of 55 years ago.

Woman in a Dressing Gown returns to selected cinemas from today, ahead of a DVD release on August 13.

"The Man Inside" (Metro 27/07/12)

The Man Inside (15) 95 mins ***

A double

meaning lurks in the title of Dan Turner’s confident urban thriller, which

attempts to update the old-school boxing melodrama with torn-from-the-headlines

guns-and-gangstas business. Its protagonist Clayton (UK grime sensation Ashley

“Bashy” Thomas, brooding nicely) is a talented young pugilist working out of

tough trainer Peter Mullan’s South London gym. Training is interrupted when Clayton

learns his younger brother is running with a local gang – and again when their

abusive jailbird father (David Harewood), himself a former boxer, reaches out

from behind bars. Will our boy fulfil his potential, and become his own man, or

is he doomed to follow in the footsteps of the other man inside?

Turner

comes out fighting: his script takes wild swings at Big Issues – the gang

mentality, domestic violence, abortion – connecting with them often glancingly.

If Clayton’s battles are carefully handled, erratic plotting and casting

prevails elsewhere. A romantic subplot suffers from the unlikely choice of

doe-eyed ex-EastEnders lovely and

British Liv Tyler™ Michelle Ryan as Mullan’s Gothy daughter; her drug addiction

comes from nowhere, and leads to a less-than-convincing cold turkey sequence.

Yet between them, Thomas, Mullan and Harewood display presence forceful enough

to overcome the scrappier material: in choosing hope over despondency, Turner’s

film rallies in its final scenes to land, if not a knockout blow, then a

promising victory on points.

The Man Inside is in cinemas nationwide.

Thursday 26 July 2012

1,001 Films: "The Bigamist" (1953)

One of a small but impressive handful of B-movies made by actress-director Ida Lupino in the early 1950s, The Bigamist takes the sort of "adult" material the studios of the period would have passed on, and - without sensationalism - converts it into striking, potent, eminently discussable viewing. A childless but upwardly mobile couple - travelling salesman Edmond O'Brien and his PA wife Joan Fontaine - find themselves subject to the routine investigation of kindly San Fran adoption officer Edmund Gwenn. Gwenn has doubts about the husband, confirmed when the investigator tails O'Brien to L.A., and discovers the second home he's made with another wife and a small child. The bulk of what follows is a flashback in which a contrite O'Brien tells Gwenn how he got into - as the latter puts it - "this vile position". Still, this isn't even the half of it: O'Brien meets his other woman (played by Lupino herself) on a Hollywood sightseeing tour during which they go past the "real" Gwenn's house. (Fontaine, meanwhile, is encouraged that their interrogator "looks like Santa Claus": not surprising, given that Gwenn had played Kris Kringle in the original Miracle on 34th Street six years before.)

Like her fellow maverick Dorothy Arzner, Lupino has been championed by those seeking out the all-too-scarce examples of Hollywood feminism, yet - though there's some early talk here of both "a woman's place" and "women's privilege" - the film is more sympathetic to the love rat than you might expect, or than he perhaps deserves. Allowed to narrate every last tragic irony of his situation, this bigamist is closer to the existential figures of noir than a moustache-twirling cad; certainly, the direction notes the entrapment the protagonist faces in his ostensibly successful first marriage (caught up in their own careers, O'Brien and Fontaine only rarely seem to be listening to one another), while the bigamy itself is made heroic in some fashion, as a meeting of responsibilities after O'Brien has got the vulnerable Lupino character pregnant.

This, of course, is the ambiguity B-movies specialised in; by his final scene, even the once-outraged Gwenn is forced to admit of O'Brien: "I can't make out my feelings about you. I despise you and pity you... I almost want to wish you luck." Throughout, there's an attempt to show the humdrum, quietly desperate realities lurking behind the glamour of Beverly Hills, as lived by working men and women: the other woman is the manageress of an Chinese restaurant with one authentic Asian dish on the menu, owned by "a guy who used to run a hot-dog stand". Displaying a commendable lack of vanity, Lupino makes good use of the difference in looks and style between herself and the poised, conventional Fontaine, and she gets a performance of palpably shabby sincerity from O'Brien, the missing link between Bogart and Nixon.

The Bigamist is available on DVD through Quantum Leap.

Wednesday 25 July 2012

The wonderer: "Searching for Sugar Man"

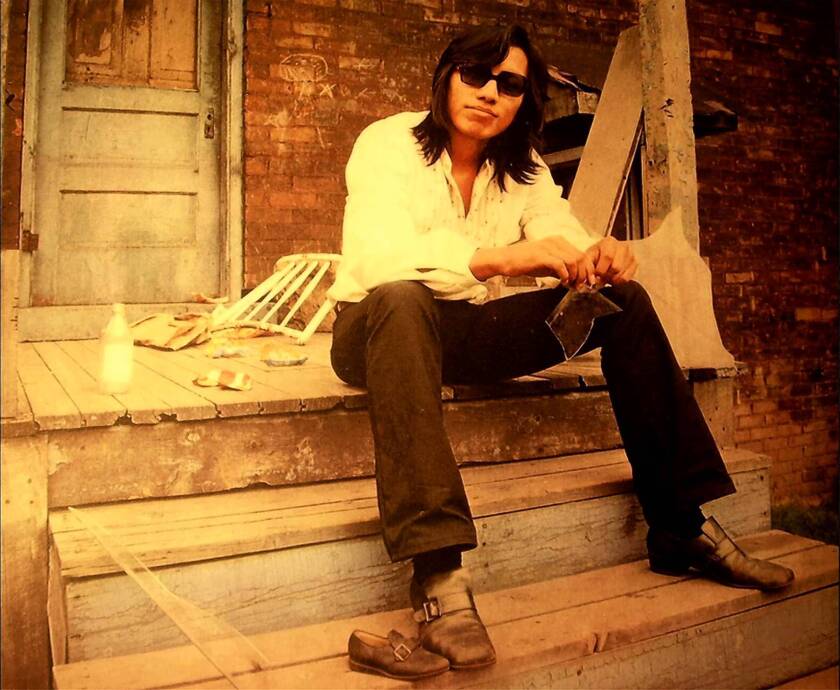

Malik Bendjelloul's documentary Searching for Sugar Man is at once an act of musical detective work, a most enjoyable reopening of a dusty Where Are They Now? file, and a disquisition on how a song titled "I Wonder" and steeped in personal and professional uncertainty at the time of its recording could be reclaimed, years later, for magic, dreams, an acceptance that, yes, sometimes good things happen to those who wait. The film's subject is Sixto Rodriguez (a.k.a. Rodriguez), a singer-songwriter who emerged out of Detroit at the turn of the Seventies, releasing a couple of critically acclaimed long-players (1970's "Cold Fact" and 1971's "Coming From Reality") before taking a precipitous nosedive off the radar. Despite major label support, and the input of the best producers on the Motown scene, somehow Rodriguez's pop career never quite caught fire - which made all the more tragic those rumours that arose subsequently, suggesting he'd committed suicide by setting himself alight on stage at the end of a despairing and disastrous final gig.

Publicity stills show Rodriguez to have been a long-haired, mystic guitar-carrier of indeterminate ethnic origin - part Dylan, part Johnny Mathis - with something of the former in his lyrics and vocal styling, though Bendjelloul has gathered the testimonies of contemporaries who assert Rodriguez actually surpassed Dylan in several respects. It was in South Africa where the singer's cause was most passionately taken up, however: here, "Cold Fact", brought into the country by an American tourist and thereafter circulated on bootleg, became a flag for anti-establishment protesters to rally around. (In bringing the spirit of the American heartlands to apartheid-era SA, this is the mirror image of Paul Simon's later "Graceland", itself the subject of a recent documentary, in which an established American artist brought the sound of the shanty town to the US, to wildly successful, a-copy-in-every-home effect.)

It was precisely that element of doubt and ambivalence in Rodriguez's songbook that appealed to this newly emergent protest movement: some indication of how socially clued-in "Cold Fact" was as an album lies in the revelation that not only were its songs banned from radio playlists when it finally received an official release, they were physically scratched out of the album's vinyl by over-zealous censors. This didn't stop a pair of the record's most passionate devotees, Cape Town record store owner Steve "Sugar" Segerman and music journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom, from collectively setting out to put the pieces of the Rodriguez puzzle together.

Using animation, talking heads and large, soulful, revealing cuts of Rodriguez's music - I'd wager Badly Drawn Boy had been listening to the singer, and to the track "Street Boy" in particular, before setting out to record "The Hour of Bewilderbeast" - Bendjelloul does a brisk, engaging job of keeping up with these amateur detectives as they follow the money around the backstreets of the recording industry and come, eventually, to join the dots. Their investigation appears to come to a halt in a cul-de-sac that reveals the poor accounting practices of major record labels in the 1970s, but then doubles back with a (probably not unguessable) twist signalled by the wonderfully simple, eloquent and suggestive image of a window being opened.

Yet this would make Searching for Sugar Man sound dryly theoretical, when of course it isn't: it's above all else a human story, about fandom, devotion, earned recognition, and why pop culture matters too much to be left to the likes of Simon Cowell. You can see it in the eyes of Bendjelloul's largely white and middle-aged interviewees, to whom this music, clearly, means something profound indeed - the way dreams and ideas recorded on vinyl will always seem to mean more than the latest One Direction single, downloaded from Amazon. In both the US and UK, Rodriguez remains a virtual unknown, selling precious few records on any format; this is the film that will change all that.

Searching for Sugar Man opens in selected cinemas from tomorrow.

Monday 23 July 2012

Nausea: "The Red Desert"

Michelangelo Antonioni's The Red Desert, first released in 1964 and reissued in a new print this week, is essentially two films in one. The first is a love-triangle drama involving an engineer (Richard Harris), a woman left neurotic in the wake of an accident (Monica Vitti), and the latter's husband (Carlo Chionetti), who just so happens to be the former's present employer. The second is almost a gallery piece - yes, it really is an art movie - studying other, more tangled shapes yet: the post-industrial Italian landscape forcing these characters to duck, stoop and cower. Blackened soil. Stagnant, sludgy lakes. A system that removes men from their families, then charges them for calling home, the better to turn a profit. What we're watching, it turns out, is the endpoint of the corruption that a filmmaker like Fellini rather got off on - the exploitation (of Italy's landscape, and of its labour force) that persisted through the ages into the Andreotti and Berlusconi eras.

For the ever-dissenting Antonioni, this is a terrible, terrifying thing, and as all-pervading as the smog that often drifts into shot to cloud the characters' thoughts and lungs. Vitti was never more ravishing or compelling, and her face never more Picasso-like than it was in colour - a whole Cubist landscape in itself - but it's evident her Giuliana (and, it turns out, her young son) has been badly weakened by the world around her, the electronic buzzing on the soundtrack corresponding to the vibrato of highly-strung nerves, or the ringing of the ears one often gets in rooms where large amounts of electrical equipment has been plugged in. That Giuliana has become jaded indeed is evident from her questioning of the engineer: "What do people expect me to do with my eyes? What should I look at?" Better-adjusted viewers will soon realise they could hang just about every frame of the film, even those recorded in the dark, satanic back of beyond, on their wall.

The visual design is geometric to the point of abstraction, yet The Red Desert may ultimately make for Antonioni's most accessible (and most immediately comprehensible) work: he demonstrates such a fascinating way of describing this world - tracing a ship's pipework with his camera, or allowing the actors to punch out wooden slats from a set to create an entirely new, Mondrian-like frame-within-a-frame - that it's possible not to care how little is going on dramatically. A fellow viewer described the experience as like watching paint dry, and - given Antonioni's use of colour - she's right in some respects. But the paint is toxic, and applied in brilliantly controlled strokes. It'd make a fine double-bill (for the patient) with Todd Haynes's [safe], which tops Antonioni by actually delivering its nauseous heroine to the desert; both films ask us, in their every scene, what kind of environment this might be in which to fall in love, raise kids, try and make a life for yourself.

The Red Desert opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Sunday 22 July 2012

1,001 Films: "Umberto D." (1952)

Umberto D. finds one of the leading lights of Italian filmmaking - director Vittorio de Sica - returning to the streets to point up major shortcomings in How The System Works. This is the desperately sad and painful tale of the eponymous old man (Carlo Battisti, in one of the great screen performances), trying to eke out an existence in a bug-infested guest house on the tiny state pension he's paid each week. While fighting off a bout of tonsilitis, the man's beloved dog - his sole companion, save for a pregnant maid working for a very cruel mistress - goes missing, and so, as in de Sica's earlier Bicycle Thieves, the protagonist is sent off on an allegorical quest. The substitution of dog for bicycle in this most significant of plot strands aligns Umberto D. with later films - like Amores Perros, or even Best in Show - which suggest you can tell a lot about a society from the manner it cares for its canines. However much of a realist de Sica was, he retains a misty eye for the sight of a dog turning tricks, though the script makes it clear that the protagonist is only ever looking for a little reciprocation: all Umberto asks is that somebody care for him as he has his pooch.

He's not alone in the canon. You might see Umberto as a brother to the civil servant in Kurosawa's Ikiru, or the Army men lost amongst the scrapyards in The Best Years of Our Lives, both post-War films haunted by the spectres of death and obsolescence, whose characters went looking merely to end their days with some kind of dignity. This, of course, was the great social shift of the late 20th century: that the world's population was living longer, but with increasingly fewer resources at their disposal. de Sica's film is work of prescience and still vital relevance, then: I first saw it during the so-called "pensions crisis" of 2004, a period in which even your comparatively comfortable correspondent received disheartening letters from the Government warning of "potential shortfalls" in his future pension - letters all the more disturbing because their reader saw no immediate way of getting back up to speed with the payment schedule. Seems you spend the first half of your life getting into debt, the second half trying to break even - the question de Sica's film dares to ask is: surely there has to be more than this?

Umberto D. is available on DVD through Nouveaux Pictures.

Saturday 21 July 2012

1,001 Films: "The Big Sky" (1952)

Adapted by Dudley Nichols from a novel by J.B. Guthrie Jr., The Big Sky tweaks the blueprint for director Howard Hawks's output in a way that would affect the later Rio Bravo and El Dorado: while it takes as its subject a group of men (and one token woman) under pressure - a staple of Hawks's work from Only Angels Have Wings onwards - and while it initially sets up a hierarchy between a man's man and an impetuous boy who needs to be blooded (not to mention the grizzled oldtimer who shows the man's man he still has much to learn), the film finally insists on the parity of friendship and shared experience, drawing as it does upon the story of Lewis and Clark. Kirk Douglas and Dewey Martin are the mountain men who fall in with a crew of Frenchies; the latter are sailing for the very first time up the Missouri from St. Louis to Montana, in order to trade (illegally) with the native Indians. Also on board is Teal Eye (Elizabeth Threatt), one of the natives' daughters, intended to smooth the crew's passage into Injun territory.

The Boys' Own action-adventure stuff - all done for real: the boat tipping over, a hunting party catapulting fresh meat from the hillside - is still stirring, though Hawks's real interest lies in the company these men keep, and the sparky banter they keep up, once installed around the campfire. You could warm your hands and cockles on the democratic sentiments being expressed here: the arguments in favour of free trade (and equality for the natives) receive a full and substantial airing, the heroism and courage of these trailblazers is resolutely played down, catchphrases ("Sic 'em, Boone", "Well, I'll be dogged") rise up out of the flames, and even the amputation of Kirk's finger gets spun out into an amusingly boozy set-piece. Less significant, perhaps, than this director's later oaters - the supporting cast is solid, rather than outstanding - it remains a most convivial entertainment, with a welcome shot of mythic poetry in its final moments.

The Big Sky is available on DVD through Odeon Entertainment.

Friday 20 July 2012

For what it's worth...

for the weekend of July 13-15, 2012:

1 (2) Ice Age 4: Continental Drift (U)

2 (1) The Amazing Spider-Man (12A) ***

3 (new) Magic Mike (15) **

4 (new) Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (15) ***

5 (new) Cocktail (12A) **

6 (3) The Five-Year Engagement (15) **

7 (5) Men in Black 3 (12A) **

8 (6) Prometheus (15) ****

9 (4) Katy Perry: Part of Me (PG)

10 (7) Snow White and the Huntsman (12A) **

(source: BFI)

My top five:

3. Salute

5. Swandown

Top Ten DVD rentals:

1 (2) The Descendants (15) ***

2 (1) The Woman in Black (12) ***

3 (3) Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (12) *

4 (new) Chronicle (15) ****

5 (new) Young Adult (15) ***

6 (9) The Iron Lady (12) **

7 (new) Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance (12)

8 (8) Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol (12) ***

9 (10) The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (18) **

10 (5) The Muppets (U) ***

(source: lovefilm.com)

My top five:

Top five films on terrestrial TV this week:

1. Grosse Pointe Blank [above] (Saturday, BBC1, 11.45pm)

2. American Graffiti (Friday, ITV1, 2.35am)

3. Winchester 73 (Tuesday, C4, 1.25pm)

4. A Clockwork Orange (Wednesday, ITV1, 10.50pm)

5. Millions (Thursday, BBC1, 11.35pm)

Odd couples: "In Your Hands" and "Swandown" (ST 22/07/12)

In Your Hands (15) 81 mins **

Swandown (12A) 93 mins ***

With 2008’s slowburning I’ve Loved You So Long and 2010’s spiky Leaving, Kristin Scott Thomas was appointed high queen of summer

counterprogramming, a one-woman alternative to superheroes. The crown certainly

fits: the actress’s translucent skin makes the ideal carapace for a refined,

restrained performance style that prioritises deeply-held, semi-concealed

thoughts and feelings over bold shows of action. The po-faced In Your Hands, an odd coupling of

captivity horror and relationship drama, depends more than most on this

vulnerability: Scott Thomas plays Anna, a nervy doctor who walks into a

Parisian gendarmerie and begins to

describe her kidnap by a wild-eyed, wild-haired loon (Pio Marmaï) with a grudge.

As the heroine’s ordeal is revealed in

flashbacks, Lola Doillon’s film shrinks to the dimensions of a theatrical huis clos. Captor humiliates captive,

she responds with tenderness, the pair come to co-exist, and we’re shuffled

towards the dangerous insinuation that a singleton like Anna might just be glad

of the attention. Scott Thomas has a real challenge on her hands here – to show

an ostensibly rational woman striving to normalise aberrant behaviour – and

while she resists the set-up’s more lurid possibilities, she can’t make it grip

dramatically in the way those earlier vehicles did. Concluding limply after 81

minutes, In Your Hands feels less

like a credible narrative than a writer-director tentatively playing out her

domination fantasies: Fifty Shades of

Grey may have more to answer for than we thought.

The counterprogramming keeps on coming.

The art-film hybrid Swandown offers

the divertingly bizarre prospect of filmmaker/artist Andrew Kötting (besuited, when

not shirtless) and writer Iain Sinclair (wrapped up warm in waterproofs and

thinking cap) liberating a swan-shaped pedalo from the Hastings seafront and

piloting it inland towards the Olympic site. From the riverbank, the camera

looks on, awed, amused, attuned to the changing scenery, while the soundscape

ebbs and flows with the tides, free-associating songs, stray Sinclairisms, the

Shipping Forecast, scraps of old Albion. A Trigger

Happy TV sketch with extended footnotes, it requires a level of indulgence

– certain stretches of this route are more engaged and engaging than others –

but it’s almost unimprovably English in its mix of cheeky larks, muted protest

and melancholy, and provocative enough to suggest future ventures in a similar

vein. Something with Alain de Botton on the dodgems at Blackpool, perhaps? Gilbert and George Do Crazy Golf?

In Your Hands and Swandown are on selected release.

Wordy rappinghoods: "Something from Nothing: The Art of Rap"

With Something From Nothing, Ice-T gives us a lively overview of the art of rap - the prepwork that has always preceded the money and the women - as constructed through a series of conversations with many of the form's leading wordsmiths: Em, Dre, Snoop, Kanye et al.. You'll need to know who these figures are, and who the oft-cited 'Pac is, to most benefit from it, and I think it's fair to say the name Ice-T isn't going to become a byword for journalistic rigour: flashy helicopter shots keep threatening to remove us from the streets on which rap originated, and there's a sense T is chumming around with his interviewees, rather than pressing them on the subjects they spit out and skim over. Rap's meaning - its origins as a tool of protest, its occasional forays into sexism, homophobia and other thuggishness - is secondary to its methods here. A 90-minute primer like this can't measure up to C4's landmark series The Hip Hop Years, but the sheer cross-section of styles sought out (East Coast and West Coast; black, white and Latino; male and female) might just give it life as a repository of useful advice for any aspirant MCs out there: one consensus arrived at is "write it down". By way of additional value-for-money, a choice selection of old-school rhymes and beats graces the soundtrack, and the live performances T and his new crew capture have an urgent, often electrifying poetry about them.

Something From Nothing: The Art of Rap is in selected cinemas.

Unstirred: "Cocktail"

The director Homi Adajania's first collaboration with bestubbled, Duchovnyesque hunk Saif Ali Khan was 2005's Being Cyrus, an odd, scratchy black comedy that felt in places as though American Beauty was being pushed, altogether reluctantly, into Hitchcock territory; the film didn't get anywhere worthwhile, finally, but it was interesting as a break from the Bollywood norm. By contrast, Adajania and Khan's latest film, the London-set relationship dramedy Cocktail, is as brash, splashy and pseudo-hip as the Hindi mainstream presently gets. If you're playing Bollywood bingo, you can tick off the following: an establishing shot of the Gherkin; a male lead who works in software development; musical numbers set in nightclubs that look like no nightclub you or I have ever set foot in, and which cue the kind of songs David Guetta might manufacture, if David Guetta were a 35-year-old Asian man, and not a 58-year-old Frenchman; and native walk-on performers who deliver their lines as though they've never spoken English before.

The set-up is an unlikely flatshare scenario, beginning as sitcom, ending two hours and forty minutes later in soap. Veronica (Deepika Padukone), a partygoer whose comedy signifier is her persistent refusal to wear panties, discovers Meera (Diana Penty), a naive young thing lured to the capital by a hoax offer of marriage, sobbing in a bathroom, and invites her to stay at her place. Physically, the two could be twins, which is a problem for the film, as Penty and Padukone - previously one of the most singular creatures in all cinema - swiftly become interchangeable in everything up to and including their initials. Anyhow, their life together is all makeover montages and trips to Borough Market, until one night Veronica picks up Gautam (Khan), a seasoned tailchaser who comes to discover his latest conquest's flatmate is the fresh-off-the-plane beauty he'd earlier put the moves on at the airport. Given the two girls' resemblance, perhaps it's no surprise allegiances should shift - and the lingering kiss Gautam and Meera share while holidaying in Cape Town just before the interval leads us to expect the second half is going to be agonisingly heartfelt. Which it is.

For the most part, the stars are the only thing keeping Cocktail watchable. (It would be easy, if not especially pleasant, to imagine an American version with Ashton Kutcher, Olivia Wilde and Leighton Meester.) Khan does have charisma and comic timing - he shares some sparky moments with schlubby older brother Boman Irani - though they're laid on thick here, as if to compensate for the thinness of the premise. In so far as the film allows her to distinguish herself - and it really does take two or three glances per scene to ascertain whether it's Veronica or Meera Gautam is wooing - Penty makes an appealing debut, downplaying wherever possible, and letting her co-stars handle the zanier, sudsier stuff; and Adajania knows that, if all else fails, he can always cut to Padukone lounging around in a bikini or stepping into or out of a cocktail dress, a tactic that proves more effective than any of the script's attempts to sell us on Veronica's mid-film decision to put on an apron (and, we presume, underwear) and reinvent herself as a devoted housewife.

The problems are familiar ones, centred on Bollywood's continual inability to depict contemporary reality in any even mildly convincing fashion. I don't doubt there are Desi boys and girls at large in the City of London who work in photography or the software industry, and have disposable income enough to holiday in Cape Town and take in waifs and strays. My suspicion, however, is that this audience - which is, after all, the audience Cocktail looks to be aiming at - is getting up to far more with their weekends than smoking, taking discreet sips of Carlsberg, and wondering which of their flatmates to bat their eyelashes at. As a portrait of the London scene, Cocktail holds up only about as well as Hollyoaks' depiction of nightlife in Chester: the result is a film that desperately wants to be a Veronica or Gautam - sexy, worldly, hedonistic - but which actually, when it comes to it, proves rather closer in personality to Meera, being meek, gauche and deeply, deeply conservative.

Cocktail is on nationwide release.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)