What's been interesting about MUBI UK's summer season of New Brazilian Cinema has been spotting the points at which these diverse films tesselate and overlap, and thereby reveal shared concerns. The SF-inclined dystopia of last month's Once There Was Brasilia opened with audio footage describing the downfall of a president; turns out it may well have been clipped from the same raw feed Maria Augusta Ramos plugs into at various points through The Trial, her gripping documentary account of the downfall of Brazil's democratically elected Dilma Rousseff. A prologue describes the fractious vote in Congress by which Rousseff was made subject to an impeachment hearing: this chaotic political theatre concealed the first manoeuvres in what proved to be a drawn-out but ultimately successful coup. Some of it is eerily familiar: one pro-impeachment deputy harks on about that now-dread word "sovereignty". Some of it is specific to Brazil, but has implications for democracy everywhere else. When Ramos shows us crowds massing to watch the votes being cast on Jumbotron screens, as they would for a World Cup final, you realise the extent to which politics is becoming more and more like football: you pick a side, you stick to it, and you holler abuse in the loudest possible voice at all those who would oppose you. One deputy casts a vote in Rousseff's favour with the addendum "sleep with that, ya bastards"; I was going to joke that the hidebound processes of our own Houses of Parliament might be enlivened with a little more of that attitude, but if the past five years have demonstrated anything, it's that you have to be careful indeed what you wish for in politics. Don't we all miss the days when administration was a quiet, sleepy, dull business, when our politicians were largely anonymous, faceless, boringly competent drones?

From there, Ramos turned her cameras on the roster of committee meetings and pre-trial hearings held throughout 2016, doubtless reasoning that if her country was going to slide into fascism, it wasn't going to go unwatched or unreported. Her approach remains observational rather than confrontational, sensing this situation was heated enough. She appears to have snuck into the back of these crowded lawyers' offices and halls of power, going unnoticed in the vast and swirling media scrum. The footage she captured is often electric: it covers both major procedural turning points - those moments where the forces in play against Rousseff became clear - and telling details, like the failure of an electronic buzzer that causes one key committee meeting to enter into an unforeseen recess. (Inference: the whole infrastructure is rotten.) One potential hurdle is that we get scant briefing or guidance as to who's who, save the odd glimpse of a name plate on a desk. Yet that choice obliges us to take everyone on screen at face value, to evaluate their words, deeds and bearing, and decide whether these are the individuals we would want representing us at a watershed political moment: it's a documentary that intends its viewers to be active participants, rather than passive consumers. What's striking, possibly alarming is how many of the featured players seem to think they're here to put on a show: huffing and puffing, shamelessly playing up to the cameras, adding the odd crocodile tear for effect, and generally making a noise that drowns out any more sober appraisal of the stated facts. I fear this is a global consequence of the social-media age, when he who provides the grabbiest content, to be snipped, looped and circulated among the greatest number of people, invariably comes to enjoy the last laugh. That's how you end up with a singularly unqualified TV personality as President; that's how a small island votes to cut itself off from its largest trading partner. What Ramos wound up documenting - and plainly it has relevance beyond Brazil - is a slow divorce from reality.

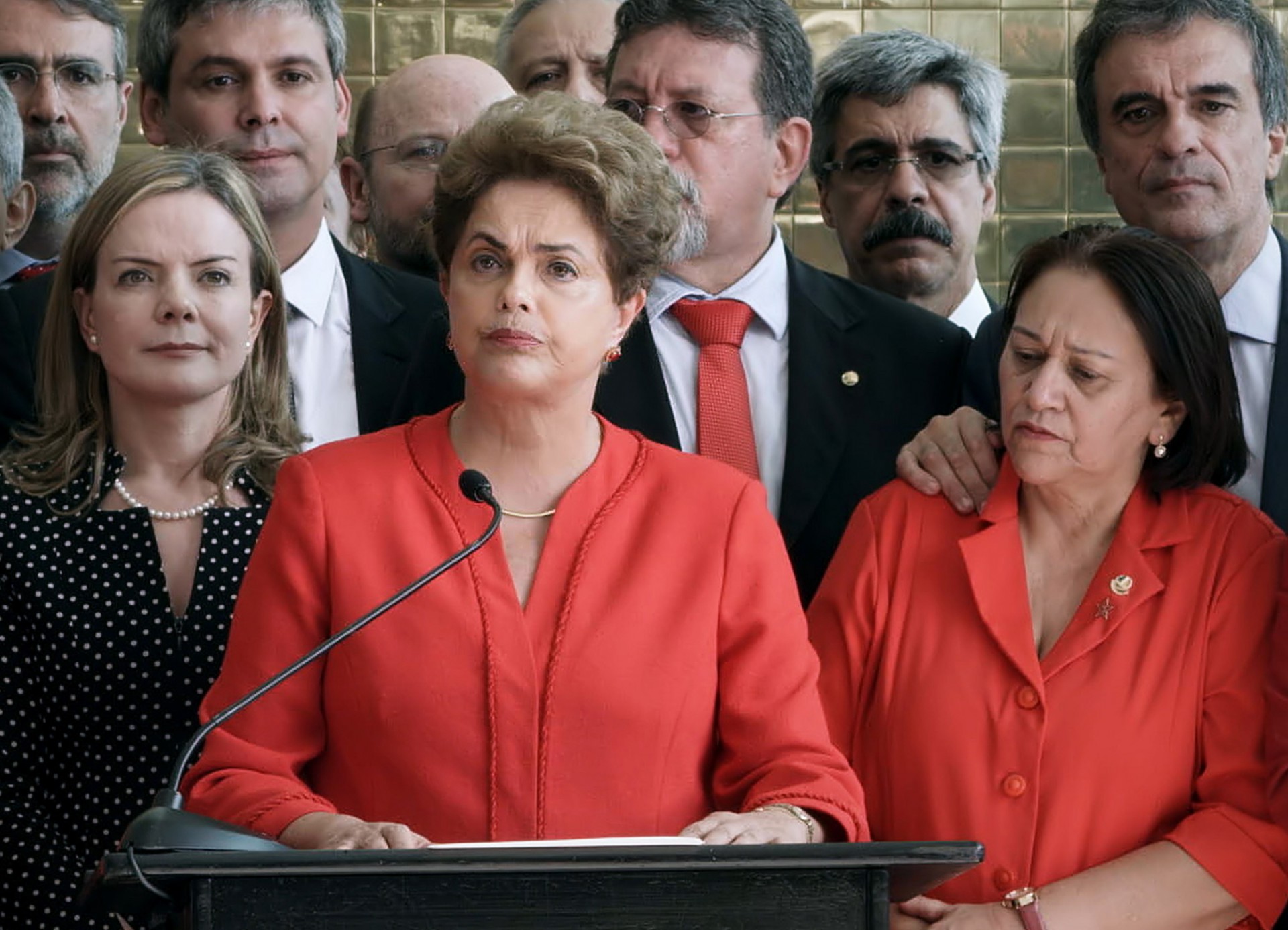

She finds a small, semi-comforting pocket of resistance in those gathering around Rousseff - a hushed, pragmatic brains trust headed up by senators Gleisi Hoffmann and Lindbergh Farias - who seem aware of the gathering storm, and seek to take corrective action rather than further stirring the pot. But it's evident the battle was being fought elsewhere: on TV, online, and in the offices of the Brazilian right, to which Ramos had only selective access. Team Rousseff's reading of this situation is nuanced, forensic, and the defence they put forwards both principled and spirited. (They actually make a better case than Dilma herself, who appears faintly remote and off-limits whenever she wafts before Ramos's camera; if she earns our sympathies, it's because we know she was preferable to what was to follow.) Yet however smart or considered the pushback they arrive at in chambers, they're continually outmanoeuvred, outshouted, out-Tweeted whenever this matter returns to the public sphere. The old certainties are no longer; the centre - represented in The Trial by a vociferous female member of the PSDB, seen receiving anti-choice Christian lobbyists shortly before her party leapt into bed with Bolsonaro - cannot hold. A coda shows the riot police entering the picture. What's chilling is that there's nothing shadowy or subterranean about this process: this democracy died in brightly lit rooms full of people, and in full view - often with the full support - of the press. If the Covid crisis has underlined anything, it's how much we can learn from other nations, provided we can set aside the blinkers of nationalism and exceptionalism. What The Trial confirms - and what makes it one of the most important documents of the present moment - is that there are now a lot of nations teaching the world how not to do politics.

The Trial is now streaming via MUBI UK.

No comments:

Post a Comment