Richard Williams, who has

died of cancer aged 86, was a legendary figure in the field of hand-drawn

animation whose name will be most closely linked with two projects, one polished

to a superlative degree, the other notoriously uncompleted. Taken collectively,

they illustrate the rewards and risks of the many painstaking hours Williams

spent hunched over the drawing board.

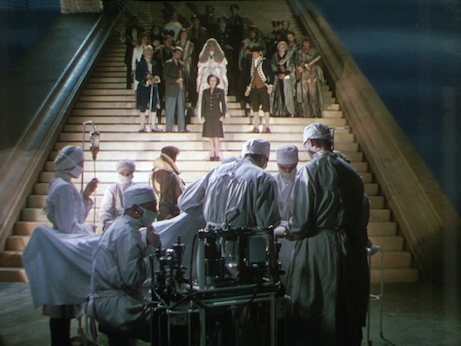

In the mid-1980s, the

greying Williams was appointed as animation director on Who Framed Roger

Rabbit? (1988), Disney’s wildly ambitious hybrid of cartoon and human

characters. Shepherding the popeyed lupine Roger through a combination of real

and virtual locations, Williams arrived at something both multidimensional and

vastly more dynamic than the flat animated landscapes of old.

The attention to detail –

at all points matching Roger’s eyeline to that of Bob Hoskins’ flesh-and-blood PI

– paid off spectacularly: having accumulated blockbuster box-office, the film

earned Williams two Oscars at the 1989 ceremony, one (for Best Visual Effects) shared,

the other an individual Special Achievement award.

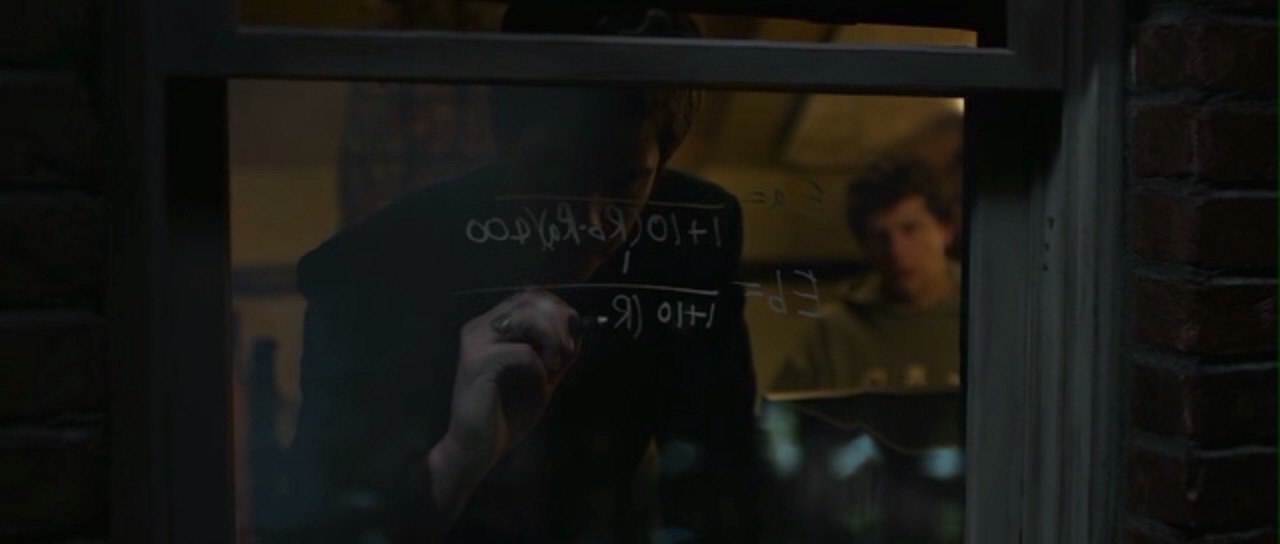

Roger Rabbit’s success tempted Warner Bros. to funnel

funds into The Thief and the Cobbler, an immersive folktale the animator

had started working on in 1964 with an eye to creating the greatest animated

film ever made.

Yet production was slow-going

even by animation standards, and by 1992, with the resurgent Disney’s vaguely similar

Aladdin looming, the plug was pulled on Williams’ endeavours. Existing

footage was then recut and issued twice by impatient producers keen to get some

return on their investment: first as The Princess and the Cobbler

(1993), then – when rights reverted to Harvey Weinstein’s Miramax – as Arabian

Knight (1995).

Neither cut found much of

an audience, and whatever greatness lay in Williams’ original vision appeared

to have been lost forever. Understandably bruised, Williams refused to watch

either of the commercially available versions, reasoning: “My son… told me that

if I ever want to jump off a bridge, I should take a look.”

Yet Williams’ own pencil-test

workprint of Thief eventually appeared online, leading fans to assemble

what became known as the Recobbled Cut, preserving those surreal, shimmering

flourishes hacked from earlier variations. In recent years, Williams toured the

world with this version, sharing what he’d taken from this long, troubled

process.

He was born Richard

Edmund Williams in Toronto on March 19, 1933, the son of Kenneth and Kathleen

Williams (née Bell), an illustrator who’d once been offered a job at

Disney. “She took me to see Snow White when I was five and said that I

was never the same again,” Williams recalled in a 2013 interview. “Not that I

was scared like all the other children who thought the creatures were real. I

knew they were drawings, and that’s what fascinated me.”

A keen scribbler, he visited

the Disney studios aged 14: “I was a clever little fellow, so I took my

drawings and I eventually got in… I was in there for two days.” After art

school, he headed to Ibiza in 1953 with the ambition of making it as a painter;

soon, however, he found “the paintings were trying to move”. He relocated to London

in 1955 and found work in various animation studios, including those of the

emergent Bob Godfrey: “I worked in the basement and would do work in kind, and

he would let me use the camera… [it was] a barter system.”

That Williams was deviating

from the Disney norm became evident from his early shorts. The Little Island

(1958), which won the Best Animated Film BAFTA, was a half-hour allegory in

which three figures representing truth, beauty and goodness jostle for

supremacy. Subsequent productions – The Wardrobe (1958), A Lecture on

Man (1962), Love Me, Love Me, Love Me (1962) – confirmed his rising

status.

Williams’ early work on Thief

was funded by a new revenue stream: providing title sequences and animated

inserts on big-budget features. As London swung, he contributed graphics to What’s

New, Pussycat? (1965), A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum

(1966), Casino Royale (1967) and, most prominently, The Charge of the

Light Brigade (1968), where he rendered warring national forces in satirical

penstrokes. His opening credits for The Return of the Pink Panther

(1975) and The Pink Panther Strikes Again (1976), rendering the misadventures

of a flamingo-coloured cat burglar to Henry Mancini’s jazzy score, are arguably

better remembered than the features themselves.

His company Richard

Williams Productions, bolstered by veteran animators laid off by cost-cutting

studios, enjoyed an early triumph with their 25-minute adaptation of A

Christmas Carol (1971), winner of the 1972 Oscar for Best Animated Short.

Less successful was the

feature-length Raggedy-Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure (1977), which

Williams took on only after original director Abe Levitow died, whereupon he

underwent several draining creative clashes with studio Fox: “The lesson I

learnt was the Golden Rule – whoever has the gold makes the rule.”

Yet he won an Emmy in 1982

for Ziggy’s Gift, a Christmas TV special based on a newspaper comic

strip, and crafted memorable work in the commercial sector, animating Tony the

Tiger and the Cresta Bear among other adworld avatars.

He won the Winsor McCay

award, named after a previous animation pioneer, in 1984, and alongside his

fourth wife, the producer Imogen “Mo” Sutton, received another Oscar nod in

2016 for Prologue, a mesmeric study of Spartan and Athenian warriors,

based on an idea he’d had as a fifteen-year-old. (Its working title, according

to the then-eightysomething Williams, was “Will I Live to Finish This?”)

By then, he’d become an

avuncular elder statesman, assembling The Animators’ Survival Kit, a

do-it-yourself guide published in 2001 and later reconfigured as an iPad app. Working

out of Aardman’s Bristol studios, he embraced Twitter, offering real-time

mentoring, while reflecting on his legacy: “If I did things again, I would be

wiser, but you get wise too late. I was so interested in the work that it

blinded me to what was going on. And the work is just so damn fascinating you

feel as if nothing else matters."

He is survived by Sutton

and six children from three previous marriages, including the animators Claire

and Alex Williams, and the painter Holly Williams-Brock.

Richard Williams, born March 19, 1933, died August 16, 2019.