Thursday, 4 July 2013

1,001 Films: "Falstaff: Chimes at Midnight" (1965)

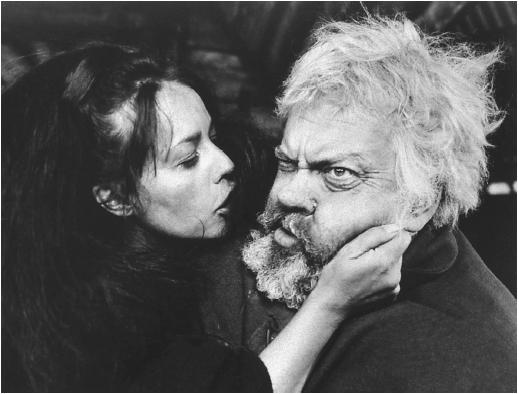

Dating from Orson Welles' period in exile, Falstaff: Chimes at Midnight stands as a notionally more democratic, alternative-angle mash-up of several key Shakespearian texts, as undertaken by a writer-director clinging to such lines as "Give me the spare man/And spare me the great ones" as cold comfort at a time when his legacy was being superceded by a whole new wave of movie brats. As with Othello and The Trial, it scores by grounding its action on sites where it looks like these dramas might actually once have played out: it's very much a product of the same decade that gave the world Pasolini's rough-hewn Trilogy of Life, although with Welles at the helm, the results inevitably skew starrier, finding spots for Jeanne Moreau (rehearsing proto-Eva Greenisms as the local harlot), Marina Vlady and (oddly enough) Margaret Rutherford as a hostess.

Though Welles is respectful enough of the texts (and Shakespearian mores) to cast Gielgud as Bolingbroke and deploy Ralph Richardson as his narrator, the focus isn't on the castles (with Kane and Ambersons, Welles had already broached the downfall of kings) but on the kinds of taverns and bawdy-houses the director himself was fond of frequenting off-screen. In assuming the role of Falstaff, the writer-director-star could restructure whole plays around his expanding waistline, effectively recrowning himself in the process: the assumption throughout is that we'd rather hang out with this Player King than with the pinched and sneering Gielgud. Even when Falstaff is pretending to be the latter - "Play out the play, man; play out the play - I have much to say on behalf of that Falstaff" - he intends to be talking about himself.

That emphasis on playing, the delight in dressing up and attempting such impersonations, is key. Though the verse is rendered somewhat crude and inelegant in places by obvious post-synching, it may not be entirely inappropriate in this instance: the film is as much a repository of fat jokes as were later Eddie Murphy or Martin Lawrence vehicles. Say what you - or yo' momma - like about Shakespeare, struggle as we collectively might to keep up with the exact meaning of the lines, the guy wrote some more than halfway decent insults and putdowns, rather gleefully compiled here by a performer all too aware of his increasing girth. Falstaff alone is on the wrong end of such as "you clay-brained guts", "a gross fat man - as fat as butter" and "your means are very slender - and your waist is great". (Snap!)

On a conceptual level, one senses Welles responds less to the Bard's high art than to his low blows, something closer to the gutter he found himself in. Visually, however, there is enough evidence here to suggest how Welles's cinema actually benefitted from being removed from the American system: dynamically shot and edited, possibly to hide the meagre resources left at its maker's disposal, Chimes at Midnight has the invention and immediacy of so much oppositional world cinema emerging around this period. The battle sequences, in particular, are right up there with The Round-Up in a compositional sense, and have the urgency not of hidebound costume drama, but something like The Battle of Algiers on horseback. Its idiosyncrasies may count against it overall, but it's a very solid leftfield contender for the title of Best Filmed Shakespeare - and would have been a far more dignified way for Welles to have shuffled off the stage than all those aborted ad campaigns of the 70s and 80s.

Chimes at Midnight is available on DVD through Mr. Bongo.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment