Monday, 30 April 2012

Old boys' club: "American Pie: Reunion"

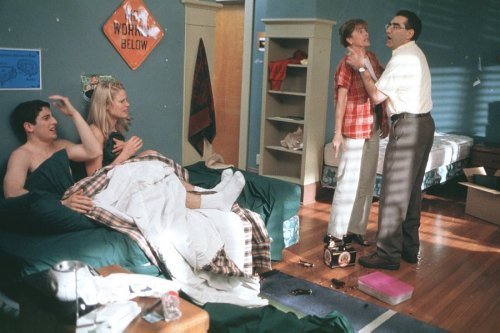

The premise of American Pie: Reunion is that the fresh-faced virgins we first met back in 1999's American Pie have grown up into sexless, middle management-inhabiting, reality TV-watching mediocrity, which anyone who's been following the careers of Jason Biggs, Chris Klein, Eddie Kaye Thomas and Thomas Ian Nicholas over this past decade will soon realise has a kernel of cruel comic truth within it. Jim (Biggs) and his ditzy beloved Michelle (Alyson Hannigan) - last seen getting hitched in 2003's American Wedding, now bringing up baby - have been reduced to taking their sexual gratification from shady websites and the showerhead respectively, which seems somewhat banal, given Michelle's previous aptitude around the woodwind section. Nicholas's Kevin, meanwhile, is being held prisoner by a fiancee who subjects him to nightly episodes of Real Housewives and The Bachelor. "Do you know who my favourite housewife is?," Jim asks him over the phone. "It's you."

The one member of this gang who's refused to grow old gracefully is, inevitably, Steve "the Stifmeister" Stifler (Seann William Scott), who - whether marching up to complete strangers to inquire "who's this douche?" or prescribing banging an 18-year-old as the cure for Jim's bedroom blues - is the jolt of rude comic energy a lagging franchise like this badly needs. Stifler remains the one Looney Tune character - a pottymouthed Tasmanian Devil - in this pack of new fathers and corporate drones, and American Reunion, which gathers the boys together once more on the occasion of their high-school reunion, perks up by a factor of ten whenever Scott, and his broadest of shit-eating grins, is on or around the screen. Otherwise, the new film - ignoring that rash of direct-to-DVD sequels (Band Camp, The Naked Mile, Beta House) that now show up on Viva in the early hours and are best left there - has been compiled exclusively for those male viewers who were themselves virgins (or, at best, inexperienced) at the time of American Pie, and have since grown up and settled down only to be baffled by the perceived sluttiness of young girls nowadays, by gay marriages, by the fact their former sweethearts have grown old and fat in their Facebook photos.

In these bromantic times, perhaps it's inevitable that the women who were as much a part of those earlier films barely register at all in the new venture. They're left on the sidelines while their beaux decide whether or not to swap them with other guys or cheat on them with younger models, or - in perhaps the most notable and proactive example - employed as a topless prop for an entire ten-minute stretch of slapstick. Of course Tara Reid and Mena Suvari were going to sign up again, given how their careers have stalled, but it seems criminal that Reunion should only have come up with one scene for Natasha Lyonne - whose droll, proto-Lohanisms were key to how those earlier Pies undercut the maleness of their enterprise - and that said scene should begin (and more or less end) with her speaking the line "Just so you know, I'm a lesbian now."

It would be unfair to say there aren't laughs in or things to be enjoyed about this sketchy, patchy, overlong venture. At its best, American Reunion evokes the cosiness of being back among old friends: the manoeuvring-on of minor characters from the earlier films takes on an inspired, knowing lunacy towards the end, and the new directors, Jon Hurwitz and Hayden Schlossberg, bring from their Harold & Kumar work some facility for tempering the gross and the crass with the heartfelt and sincere. They at least realise that the heart of this franchise is the relationship between Jim and his dad (here, newly widowed, and again played by Eugene Levy) - one of the few father-son relationships in modern American cinema to be entirely healthy, for all its toe-curling frankness.

Yet too often in Reunion, the emotion appears only half-felt, there to justify a comic default mode of laziness: passing references to Chumbawumba, scenes that fall back on characters wearing S&M gear (generally a lameness klaxon) to get whatever laughs they do. What's happened is that American comedy has itself matured over the last decade, and in the age of Judd Apatow and Tina Fey, Lena Dunham and Glee, or even those self-same Harold & Kumar flicks (which rescued John Cho, a minor player in the early Pies, from being forevermore known as "the MILF guy"), it may no longer be enough in itself to make jokes about the struggles of white boys to get laid, in movies where everyone sips their beer from plastic cups. Like the analogue jazz mags in Jim's top drawer, or the Montell Jordan and Blink 182 records we hear on the soundtrack, American Reunion is finally just a little too Y2K.

American Pie: Reunion opens nationwide from Wednesday.

From the archive: "American Pie Presents Beta House"

American Pie Presents Beta House is American Pie 6, by my reckoning, and if you're wondering where the previous two sequels got to, you clearly haven't been spending enough time in the videoshop: instalments four and five went straight-to-DVD. With the exception of series talisman Eugene Levy, who can't surely be this desperate for the work, the rest of the cast (yes, even the Thomas Ian Nicholases) and most of the writing and production team have moved on; these increasingly cheap products are a(nother) sign of the extent to which Hollywood is becoming overrun with slick-tongued fratboys who once jerked off to a Betamax copy of Meatballs and have determined to recreate their experience for today's 15-year-olds.

The narrative throughline appears to be Steve Stifler's younger brother and cousins, background characters in the earlier, theatrically released sequels, and now old enough to enrol at university themselves. Played by slappable smirkers substantially less charming and funny than Seann William Scott, these young Stiflers here take up the cause of Beta House, rightful home of feckless party boys, whose rivalry with Geek House has been aggravated by the fact the hottest women on campus hang out with these dotcom millionaires-to-be - because, as we all know, women are only after the contents of a guy's wallet.

The Simpsons, famously, went from strength to strength after shifting its focus from Bart to Homer, but the Pie franchise seems to have undergone a disastrous paradigm shift: dropping the good-hearted (if hapless) Jim (Jason Biggs in the first three films) to pitch its camp very firmly and unironically among the Stiflers of this world. Beta House operates under the mindset that fraternities - and their stupid fucking pledge tasks - are the second coolest thing in the world; the coolest, of course, being that projectile vomit can turn a woman's T-shirt opaque, a "gag" so hilarious it immediately gets replayed on video.

In retrospect, one of the most appealing aspects of the originals was the manner in which they combined gross-out laughs with hard-won life lessons; they were romantic comedies as much as they were sex comedies, which demanded, and insisted, its female characters be as strong as, if not stronger than, the boys serving as on-screen surrogates for the male writer-directors. One can only assume viewers approaching college age are going to be severely disappointed when reality fails to measure up to the expectations raised in the course of Beta House: the women here are perpetually hot-to-trot floozies played by surgically reconfigured no-marks, recruited chiefly for their willingness to perform regular T&A duties. I never thought a franchise could make one long for the halcyon days of Tara Reid, but apparently it is possible.

(December 2007)

From the archive: "American Pie: The Wedding"

It's almost a quarter of a century since the first Porky's film hit cinema screens, and I commemorate this most dubious of film anniversaries only now, upon the release of American Pie: The Wedding, the third and possibly final entry in the series, to point out that there must be very few people waiting for Porky's 7: Pee-Wee's Nuptials or that Bachelor Party-Screwballs match-up. That first wave of teen sex comedies didn't have much time for romance, much less marriage; the only institution those characters are likely to have been invited to in the last ten years would be a sex offenders' clinic. By contrast, American Wedding (to use its abbreviated US release title) arrives as a logical progression in the Pie series.

The first American Pie, from 1999, had its young males looking to score, but there's no way those characters would have gone looking in a brothel of the Porky's persuasion, no way a post-AIDS sex romp like it would have considered depicting sex without a condom - and no way the filmmakers would pass up the opportunities this provided for jokes centred on the expansive qualities of latex and the explosive properties of semen. 2001's sequel devoted itself to making its young men better lovers: if you can't have sex with someone you love, the film proposed, at least do it with someone you know, and can trust. Well, that trust will get you places: now we find Jim (Jason Biggs) preparing to take his teenage sweetheart Michelle (Alyson Hannigan) up the aisle. Oh do stop sniggering at the back.

The defining characteristic of these films is how sweet they are, certainly in comparison with the low-budget scuzziness of their early 80s inspiration. The American Pie films are as safe as their radio-friendly soundtracks, as safe as that slightly prim manner in which all its characters drink from plastic cups, rather than swig from the bottle, at apparently wild and unchecked house parties. Increasingly, the series has become more about consolidation, building on its strengths, than about consummation: the opening credits of American Wedding are set to James's "Laid", and you'll note the past tense there: if this is to be the final instalment, then the series finishes not with a bang, but a post-coital kiss-off.

That's especially notable in the way the cast has been pared away over the trilogy. Compare the original poster - its hot, young, mixed ensemble jostling one another for space - with the poster for this latest, which appears to be operating a strict ranking system as the principals line up to disappear into infinity: Eugene Levy (Jim's dad) and Seann William Scott (Stifler), the most amusing players in the first two films, have been promoted, but Eddie Kaye Thomas and Thomas Ian Nicholas (whose appearances in the film are so few and far between a colleague wondered whether they might forsake a co-starring credit for one as "most persistent extra") have been relegated to a very distant background.

Most noticeable is the gradual downsizing of its female cast: standouts in the first film, reduced to thankless parts in the sequel. You may find yourself missing Natasha Lyonne, Mena Suvari and Tara Reid (well, two out of three), but then the reason the original's female characters were so prominent was that they were of a type previously unseen in this genre - smart, tough, and with real emotions. (These girls weren't going to put out for just anyone.) That last factor, in a series reliant on safety and formulas, upon sure things, may be the reason they're not recalled for AP3: instead, we get a pair of strippers at a stag night (where we know what they're going to do) and newcomer January Jones as Cadence, Michelle's sister and the cinema's least likely expert on Cartesian thought. Cadence, over whom Stifler and Finch come to squabble, is a more or less conventional love interest; she's there - as Descartes himself would surely observe - as a point of reference, to let us all know exactly where we are.

Writer Adam Herz, who's done a pretty good job marshalling the series to this point, has come up with a grab-bag of sketches allowing the players to push their characters a little further along the line. Biggs stumbles into even greater embarrassment: whether it be exposing his erect member in a high-class eaterie or getting involved in what looks like a threeway with Stifler and a dog, it seems every other scene in the new film's opening half-hour ends with hs trousers around his ankles; one of the upshots of a successful teen raunch franchise, it would seem, is that its principals need no longer tighten their belts. Hannigan, given less screen time, nonetheless retains her sweetly perverse presence, that air of spacey nymphomania in her eyes; the film's barely five minutes old and she's on all fours, purring like a pussycat. And what is there still left to be said about Seann William Scott? By rights, the combination of that shit-eating grin and his appearance in Bulletproof Monk should count heavily against the guy, but it's just about impossible not to warm to someone who, within moments of his first arrival on screen, has delivered the words "my dick looks like a corn dog, I got cake all over my balls" with such matchless aplomb.

Stifler is here even more profane than he was in the first two films: he asks Jim what "the Stifmeister"'s defining characteristic is, and takes the response - "uses the F-word excessively" - as a compliment. Yet it's in the downtime between the cussing and gross-out that Herz does his real work, throwing different ideas of masculinity up against one another: the intellectual Finch versus the wholly instinctive Stifler; the latter's boorishness against the sheer likability of Jim; even Jim against his own father, with their contrasting generational ideas of what it is to be a man. The jokes only stop once Stifler kills the wedding flowers, and it may be typical of this most soft-hearted of series that the only thing that gets hurt is the horticulture, yet even this is no lasting problem - the high school footballers Stifler's been coaching are soon arranging the floral replacements and rehearsing the wedding ceremony by themselves. Even the Steve Stiflers of this world must grow up eventually, we are to understand, though it's Michelle who gets the by-words of a franchise remaining clean-cut to the very end: "Love isn't a feeling - it's about shaving your balls for somebody."

(August 2003)

From the archive: "American Pie 2"

The real difference between the first American Pie and a teen sex comedy of the Porky's persuasion was that the horny young men of the former would never dream of frequenting a brothel. AP1 preached sex with, if not someone you love, then certainly someone you know; the inevitable sequel - American Pie 2, written (again) by Adam Herz, and directed by newcomer J.B. Rogers - is dedicated to making its young men better lovers. According to Herz's script, this is a matter of saying the right things over and over again, of constant reassurance intended to make both parties comfortable. Herz makes sure his viewers are on safe ground for the sequel, reprising key lines and situations for anyone who came in late, though he's a little too in love with his own semi-iconic dialogue ("This one time, at band camp..." gets thrust into cinematic lore through sheer repetition). Most teenagers will, I suspect, obtain just as much enjoyment from these re-runs as they did first time around: hot sex unintentionally broadcast to an audience of hundreds (AP2's medium of choice is CB radio rather than the Internet, which can't help but seem a little retro), parties that get so wild everyone continues to drink from paper cups and listens to Blink 182 songs. The round-up of even minor characters from the original is so scrupulous that our leads often have to prompt one another whenever another half-remembered face appears: "Who's that?" "It's Stifler's brother."

The entire cast's willingness to return - a major selling point - is a tribute to the roundedness (not to mention success) of Herz's first script, if not quite his second: Mena Suvari and Chris Klein are stuck in roles that seem to have shrunk in inverse proportion to their foreheads, and the female characters have been put to one side rather. Tara Reid and Natasha Lyonne are stuck with summer jobs in a clothes shop while their male counterparts work on renovating a house - a house belonging to fantasy sex objects at that - and simultaneously rebuilding friendships that may have suffered from time apart at college. The acting honours are therefore taken by Alyson Hannigan, who here turns her band-camp kook Michelle into something dementedly sexual (and genuinely touching), and Seann William Scott as Stifler, who - after Road Trip and Dude, Where's My Car? - seems to be building a whole career out of his note-perfect impersonation of a particular species of gormless American lunk. (At least, one hopes it is just an impersonation.) American Pie 2 is nevertheless filled with a late-summer melancholy, the sense that its little boys and its subgenre have maybe had their day. A major set-piece, in which hapless hero Jim (Jason Biggs) superglues his hand to his penis, plays out on the theatre of cruelty (rather than the mere embarrassment evoked in the first film), with a soundtrack of rips and squelches alternating with Alien Ant Farm. The jokes in an intermittently funny and mostly enjoyable film dry up half-an-hour from the end, Rogers losing the comic momentum Herz has previously built up; but then the sight of these characters growing up and settling down was never going to be as much fun as that of Stifler getting urinated upon, or of two lesbians making out with one another.

(September 2001)

American Pie 2 screens on ITV2 this Thursday at 11.15pm.

From the archive: "American Pie"

American Pie largely succeeds in delivering what it promises: a 15-rated studio-backed version of those 18-rated independent sleazefests from the early 1980s. It keeps the general narrative thrust of the Porky's/Screwballs movies - a bunch of guys try to lose their virginity - but knocks the corners off its now mostly sympathetic male characters, and crucially casts smart, talented actresses in the roles of no-longer-sex-object females blessed with post-feminist thought. Its money scene - the one we've all seen in the trailer - features a horny lad getting intimate with an apple pie; tonally, it's a million miles away from similar scenes in Philip Roth's novel Portnoy's Complaint and Jean-Claude Lauzon's 1992 film Léolo, where raw liver was the culinary object of desire, an instant course in the fleshy carnality of adolescence - the apple pie here is symbolic of how the sex comedy has had to be sweetened to be anywhere near palatable in the post-AIDS era.

One could say it's been artificially sweetened: a last-reel gearshift doesn't come entirely naturally, interrupting the characters' sincere expression of sexual and romantic ideals with endless cutaways to cheap gags. This is the big tease of Porky's, reconfigured to fit a gross-out comedy released in the wake of the Austin Powers films: a series of delayed climaxes, pay-offs waiting to happen. Still, those gags are well sustained by a diverse and enthusiastic cast: with a name and a look like that, I sense Mena Suvari will be a screen goddess in years to come, and Eddie Kaye Thomas's Finch is a memorable comic creation, a guy who, only minutes after the virginity-losing plot has been hatched, dutifully rolls out the putter and balls to play mini-golf, cool as you like. All the favourites of the early 80s teenpics are here: spying on naked and semi-naked women, bodily fluids flying about, the free and gratuitous deployment of laxatives. Twenty years on, there's a warmness and familiarity about these old standards, like a dreadful covers band doing "Don't You Forget About Me" at prom night. Or maybe it's the warmth and familiarity of hot apple pie itself.

(September 1999)

Yo teach: "Monsieur Lazhar"

The gentle French-Canadian drama Monsieur Lazhar, another of this year's Oscar foreign film nominees slipping into cinemas to no particular fanfare, gets its punchiest material out of the way early, as two pre-teens at a school in inner-city Montreal discover the body of their beloved female form tutor hanging from the rafters of her classroom. Thereafter, Philippe Falardeau's film busies itself tidying up any mess: the body is cut down, and the walls of the classroom are being repainted when the bearded Algerian of the title (the engaging Fellag) walks into the headmistress's office. Citing what he claims were nineteen years of educational experience in his homeland, M. Lazhar lands the job of teaching replacement a little too easily; even School of Rock, fast becoming an unlikely touchstone for this sort of thing, knew it had to put us at ease with a couple of well-placed jokes.

I think we're meant to take it on trust that a film this impeccably middlebrow wouldn't go anywhere too discomforting, as indeed proves to be the case. Instead, we watch as Lazhar slowly gets his feet under his late colleague's desk, making ripples rather than waves en route. In some ways, it's the decaf version of Laurent Cantet's Palme d'Or-winning The Class, itself nominated in Oscar's Foreign Film category a few years ago. The pupils are younger and less bolshy, granted - they make mischief, not trouble - but the classroom scenes adhere to a similar, back-and-forth rhythm: Lazhar learns not to inflict Balzac on his charges, while their pleas for him to teach them something of himself - insistently waved off - are interrupted by a sudden nosebleed. Where the films differ is in their content. The Class, seizing upon the school as a microcosm of multicultural France, found conflict and disharmony (and great potential) almost everywhere Cantet pointed his camera. By contrast, Monsieur Lazhar is all a bit too, well, Canadian: the worst that happens to the protagonist, even after he smacks one of his pupils aboot the head, is that someone plants a sticker of a fish on the back of his jacket without his noticing.

Falardeau crafts some nicely unstressed business between Lazhar and Abdel, the one kid in this class who gets his teacher's asides in Arabic, and it's hard to take too unkindly against a film where the school play takes in the opening of the Suez Canal - but then the reason this is funny is precisely because it's a dash of incongrous, even ambitious drama in a film otherwise content to muddle along in the minor key of an afterschool special on Why We Have Different Surnames. Altogether too neat in its paralleling of teacher and pupils - both, it turns out, mourning the loss of a woman close to them - Monsieur Lazhar needed some greater disruptive element: the at-the-blackboard presentations in The Class highlighted and accentuated real-world ructions, but here we're left with an angelic blonde Pollyanna who insists "My school is beautiful. Maybe not the most beautiful, but it's mine."

Monsieur Lazhar opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Comes back around: "Clone"

Here's how the movie marketplace now works. Hungarian director Benedek Fliegauf's second feature, a wispy, gynocentric SF offering, has been sitting on the shelf for a couple of years under the title Womb, and only now emerges repackaged - with top-billed Eva Green secondary on the artwork to the face of current Dr. Who Matt Smith - under the apparently less offputting, literally generic title of Clone. With its oceanic vistas and emphasis on motherhood, the film itself is unalterably cyclical, returning to the same or similar images time and again, on each occasion seeking to refresh them with new narrative information - though whether or not Fliegauf is entirely successful in this is very much open to question.

After a portentous, pause-heavy sketch of a pair of childhood sweethearts living in a damp coastal town situated who-knows-where, we flash ahead in time: moving into her late grandfather's house in the dunes after a stay with her mother in Tokyo, Rebecca (Green) takes up once more with Tommy (Smith), the boy she used to canoodle with. She's now a woman of the world, and Green, one of the few young actresses around capable of suggesting smarts and feelings as well as movie-selling beauty, plays her as such; he, on the other hand, is a shambling oddball in terrible knitwear who's spent the years keeping snails in matchboxes and cockroaches in drawers, thus immediately testing the credibility of any film that suggests not one but two women might be attracted to him.

What follows is a faintly trashy, B-movie plot - echoes of Frankenstein, yes, but I was also reminded of the nifty DTV item Retroactive, starring (yes!) James Belushi and Frank Whaley, and the more recent Spanish thriller Timecrimes - played out to ponderous silence as a glumly tragic Europudding that involves Tommy's dying, lingering shots of the swelling Green belly, and the presence of a cloning facility just round the corner, as though it were a branch of the Spar. (At least Retroactive and Timecrimes made their mad scientists recluses.) Fliegauf is trying to say something about the right of women to do whatsoever they like with their bodies (and the problems they might face doing so in the future), which makes me wonder if Clone wouldn't have been better off preserving its original title - so as to be remarketed in the pages of Grazia magazine as an unusual chick-flick/sci-fi hybrid, rather than risk the yawns of fanboys who just want to see Dr. Who running round.

Still, with all its Meaningful Pauses, the debate never really gets going, incest remains a tough sell under any title, and for all the aptitude for atmosphere and location work Fliegauf demonstrates here - extending to one inexplicably creepy sequence involving a battery-operated toy dinosaur - the actors are a second thought, left to their own devices for long stretches. Peter Wight and Lesley Manville are comprehensively wasted as Tommy's parents, there to represent the limited aspirations Mike Leigh usually casts them for; Smith is beset by having to act first weird, then adolescent, getting unintentional laughs from one dining-table strop involving a salt shaker; Green - a great screen presence, still searching for the roles worthy of it - is visibly trying to gain some emotional traction on what remains a thin and ultimately elusive slip of a story. Between Perfect Sense and this (a recurring motif: Eva in bathtubs), she might want to steer clear of quasi-experimental, Brit-funded sci-fi for a while.

Clone opens in selected cinemas from Friday, and will be available on DVD next Monday.

Sunday, 29 April 2012

For what it's worth...

Top Ten Films at the UK Box Office

for the weekend of April 20-22, 2012:

1 (1) Battleship (12A) **

2 (new) Salmon Fishing in the Yemen (12A) **

3 (4) The Hunger Games (12A) **

4 (3) The Cabin in the Woods (15) ***

5 (2) Titanic (12A) ***

6 (5) The Pirates! In An Adventure with Scientists! (U) ****

7 (new) Lockout (15) **

8 (6) Mirror Mirror (PG)

9 (7) 21 Jump Street (15) **

10 (new) Gone (15) ***

(source: guardian.co.uk)

My top five:

1. Beauty

4. Being Elmo

Top Ten DVD rentals:

1 (6) Moneyball (12) ****

2 (1) Contagion (12) ***

3 (3) The Help (12) ***

4 (4) In Time (12) ***

5 (2) Hugo (PG) ***

6 (5) My Week with Marilyn (15) ***

7 (7) The Ides of March (15) **

8 (re) Crazy, Stupid, Love. (12) ***

9 (8) The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn (PG) **

10 (re) Warrior (12) ****

(source: lovefilm.com)

My top five:

Top five films on terrestrial TV this week:

1. Mean Streets [above] (Saturday, BBC2, 10.30pm)

2. Singin' in the Rain (Friday, C4, 1.05pm)

3. Dirty Harry (Saturday, ITV1, 10.45pm)

4. The Magnificent Seven (Saturday, five, 4.45pm)

5. The Ladykillers (Thursday, C4, 1.20pm)

Big bullies: "Marvel Avengers Assemble"

Our expectations having been lowered by the entertainingly clanky Iron Man films, varyingly insubstantial Hulks, the patchy Thor and an utterly conveyor-belt Captain America, Marvel finally connects the dots within its comic-book universe with Marvel Avengers Assemble. Emphasis firmly on the "its": there's something brilliantly, insidiously corporate in how that possessive "Marvel" has been slipped into the title card - a throwback, perhaps, to those 1950s TV shows sponsored by Geritol or Chesterfield cigarettes. Avengers Assemble, a business model masquerading as entertainment, isn't synergy so much as a synergasm: the realisation of a wet dream fanboys and Hollywood accountants alike have been edging themselves towards ever since they were thirteen years old. Well, after a decade of seeing the exact same film every summer, the constituent elements are now in place. The tissues are positioned on the bedside cabinet. The hand lotion has been replenished. An Internet connection has been established. And the grown-ups are out of the way for the evening. Let the frenzied adolescent frothing commence - or so the idea goes.

I hate to be a terrible boner-killer, but as a movie, Avengers Assemble really isn't much cop - and certainly not as much cop as we've been led to believe. Narratively, it remains at the most basic, first-draft stage: Loki (Tom Hiddleston), the baddie from Thor, has returned from Earth to run off with a glowing blue cube thing. This, the goodies - Iron Man, Thor, Hulk, Captain America, Black Widow and Hawkeye - don't like. AA's storyline is no more sophisticated than that, no matter how you might want to dress it up: it's an utterly unambitious washing line on which can be pegged the all-important, trailer-friendly set-pieces. These include Loki storming into Berlin, where he gets the locals to kneel before him and unfurls a big speech claiming we pitiful humans crave subjugation. With its too-obvious echoes of real-world conflicts - an elderly Jewish resident stands up in dissent, and is spared disintegration by Cap'n America's shield (whoop!) - this is exactly the kind of specious, phony parallel that has started worming its way into our event movies. We're supposed to buy this junking of history as proof the Avengers are fully-motivated freedom fighters, yet Avengers Assemble is very much a Loki-movie: it wants us to bow down, hand over our money, cower, coo. Marvel, as that title card seems almost subliminally to prompt.

What we're witnessing in pop culture right now is a colossal revenge-of-the-nerds moment. Geek culture, with its yen for acquisition (all that damn collecting), has aligned itself with corporate culture to bully everyone into spending non-existent money on the same damn product. See the Avengers movie, because you've seen Iron Man and Thor and two previous Hulks. Buy the DVD when it comes out, and then upgrade to Blu-Ray, with its optimum bit rate. (No matter that Blu-Ray automatically makes every movie look like a live episode of e.r. - as recent rumblings over the early footage from Peter Jackson's digital Hobbit movies only underline.) Watch it all over again in 3D, even if the medium forces you to squint through a murk the colour of the average Polish industrial town in a rainstorm. Removed from this equation is simple common sense: just look at the queues of people sleeping overnight outside the Apple store to get their hands on an iPhone upgrade they could just as easily walk in and pick up the next morning for the same extortionate price. But then, hey, we pitiful humans apparently crave subjugation: our collective gazes have been lowered by the gadgets we now hunch over to watch The Apprentice on.

Avengers Assemble collects together as many superheroes as anybody in possession of an X-Box might want, but they end up crowding and cancelling one another out: they all do the same thing in only negligibly different ways. Tellingly, it's those periphery figures that AA brings most sharply into focus: Samuel L. Jackson's grumpy cyclops Nick Fury, here rescued from the end credits of a half-dozen other films, Clark Gregg's nicely brisk Agent Coulson, the indefatigable Harry Dean Stanton (through which this studio-financed movie attempts to co-opt an element of rebel indie cool) as a security guard who - in the film's one truly amusing moment - encounters Hulk v3.0 (Mark Ruffalo) in the remains of a ruined factory and diagnoses him with "a condition". These are good actors trying to etch something out with the limited number of days they had on set, aware they don't have the luxury of their own spin-off summer franchise movie and might, you know, actually have to justify their juiciest of paycheques.

Everybody else indulges in zombie acting, aware they don't particularly have to raise their game because they've done this schtick before and an audience has turned out for it. The Chris third of the movie is more or less a write-off: the heart sinks whenever AA cuts away to Chris Evans's featureless Captain America, very much the Ringo of this supergroup, while Chris Hemsworth's Thor remains a crashing bore for anyone who doesn't have a hard-on for six-packs. The usually reliable Ruffalo gives the most self-effacing reading of Bruce Banner yet, which only compounds the usual Hulk-movie problem that the character only threatens to become interesting when he rips his shirt off and starts smashing shit up. Robert Downey Jr.'s Tony Stark remains the most completely developed personality - but having to share the screen with this bunch of no-marks gives him no-one to spark off, and it's hard not to think the actor could do this droll pantomiming (see also: the Sherlock Holmeses) in his sleep. I miss the brilliant polysexual shambles Downey Jr. used to embody in films like Two Girls and a Guy - but that was 1998, a time when the current target audience hadn't even been born, and a moment when Hollywood still hadn't completely succumbed to its pathological fear of making films for mature audiences.

With only the thinnest strands of comic-book DNA connecting us to these characters, AA starts to seem joylessly long. Kitted out with those whizzy touchscreens and that gantry flooring (clank clank CLANK) that have somehow come to define the anonymous modern event movie, it's visually underwhelming; more worryingly - given that there's another of Chris Nolan's monumentally expensive Batsulks looming on the horizon, conferring on Avengers Assemble the status of summer 2012's "fun" superhero movie - it's never particularly amusing, too often mistaking snark for wit. What jokes there are start to become tiresome through repetition: Thor doesn't get the other Avengers' references, because he's from another planet; Cap'n Stomach Crunch doesn't get their references, because he's from another time. It's all callbacks, anyway, often beyond the films themselves to the comics, establishing a further degree of alienation between the action and anyone who hasn't been hoarding rare first editions all these years.

Curiously, Shakespeare appears to have been a touchstone for cast and crew, alluded to both at points within the film and in a thinkpiece the generally smart-seeming Hiddleston wrote for The Guardian ahead of the film's release. This latter reads like an elevated form of marketing intended to pique the interest of those who wouldn't normally go near the misadventures of men in latex bodysuits; I'm no scholar, but I've read enough of the Bard to know the difference between real, involving, human drama and kids' stuff in which the good guys (who number six, remember) outshoot and outfight the bad (who in this case number but one). Avengers Assemble isn't remotely mythic, classical, one for the ages: it's just another juvenile B-movie Hollywood's PR department has bullied the world into taking under consideration as a double-A investment. Stay tuned through the end credits to lose another seven minutes of your life, and to find out what we'll all be expected to pay for again in two summers' time.

Marvel Avengers Assemble is in cinemas nationwide.

Friday, 27 April 2012

1,001 Films: "Diary of a Country Priest" (1951)

In an ideal world, Dougal and Ted from Father Ted would have gone to see Diary of a Country Priest at some point, only to find themselves stumbling out halfway through, incredibly confused, disappointed and bored. It dates from the early part of Robert Bresson's directorial career, when the soon-to-be-revered filmmaker was still obliged to prove himself tackling racy literary adaptations (Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne from Diderot, this from Georges Bernanos), but you sense him attempting to pare away any fripperies or potential scandal all the same, to reduce the source material to close-ups, faces, the very essence of what it was to be this country priest at this moment in time. This, as we shall see, turns out to be a double-edged sword.

What perhaps attracted Bresson to this material is that the protagonist is himself a minimalist, wasting away on a diet of dry bread dipped in wine out of a refusal to do (or, presumably, eat) anything that might compromise his core philosophy. The priest's existence is similarly reduced to nuggety anecdotes in which he settles into his new community, deals with the various concerns of his parishioners, wrestles with his faith, and then goes on to struggle, gravely, with his health. In the film's starkest images, we see him writing up the day's encounters and conclusions in his own good book; in the beginning (and the end) there is the Word.

All this writing can, however, only generate more writing. You see why Godard, himself no stranger to flooding the screen with inky splurges, would have been drawn to the film; you can also imagine scores of Schraderites writing very academic essays tying the priest together with the notionally less moral hero of the later Pickpocket. Yet Diary may just be one of those films more intriguing to write about than to have to sit through; for non-believers or doubters, it'll prove a Sunday school-like chore, in part because the dilemmas the priest faces up to are of another century, in part because actor Claude Laydu - a very Bressonian lead, unadorned, without airs or graces - remains such a miseryguts one wonders why his priest pursued this path in the first place. I don't doubt the film holds a particular place in the cinema of spirituality, but it's the subsequent A Man Escaped - a scenario that holds up whether or not you believe in a higher power - which remains Bresson's true breakthrough film.

Diary of a Country Priest is available on DVD through Optimum Home Releasing

Thursday, 26 April 2012

1,001 Films: "Pandora and the Flying Dutchman" (1951)

Pandora and the Flying Dutchman was a pretty singular reverie to have escaped from the tightly regulated confines of the Hollywood dream factory, offering as it did a fevered mash-up of the Flying Dutchman myth, Omar Khayyám's Rubaiyat, and several other poems and legends; only personal taste will decide how much of it takes. It's the one in which destructive beauty Ava Gardner sees off one suitor (self-sacrifice) and one race car (pushed off a cliff) before crossing paths with the eponymous Hollander (James Mason), who's moored himself off the Spanish coastal resort of Esperanza, convinced he's going to have to spend centuries searching for the one woman who truly loves him. (Some days, I know exactly how he feels.)

Emerging from the same period that brought us such studio-backed follies as Spellbound and The Fountainhead, Albert Lewin's melodrama casts its net far and wide - that Pandora should be distracted so is no surprise, given the plot crams in bullfighting, Tarot cards, magic potions and attempts on the land speed record - and not all of it hangs together: Mason, in an unusually dour assignment, looks vaguely uncomfortable, and your response to the film as a whole may very well depend on your response to the passing of his dog. Surrender to it whole, though, and you'll discover a rare intensity of feeling, colour and mood: exactly what one might expect from having Gardner, at her loveliest, before the camera, and the ultra-literate Lewin, not to mention a technical genius of cameraman Jack Cardiff's standing, behind it.

As Pandora confronts the portrait of her the Dutchman has completed, breathlessly uttering "It's not me as I am at all; it's what I'd like to be," we finally realise what Lewin is striving so damn hard to get at here: the ability of art, and of the image in particular, to move us to a higher place. You can tell the gamble didn't quite pay off from the failure of its location to pass into lore the way Shangri-La or Brigadoon did, but there's still plenty for the committed romantic to swoon at here: not least the sight of characters who - no matter what tragedy befalls them, and that it might be easier for them to haul anchor and sail away - continue to live in Hope.

Pandora and the Flying Dutchman is available on DVD through Park Circus.

Wednesday, 25 April 2012

Cowl me maybe: "The Monk"

With The Monk, the German-born, French-based director Dominik Moll sets out to give Matthew Lewis's 18th century novel the full Gothic treatment: it's all swooning maidens and thunderclaps, there perhaps to disguise an underlying lack of purpose. At its centre is Brother Ambrosio (Vincent Cassel), a monk plagued by headaches and nightmarish visions; a hero to his fellow brothers, who see him as the last bastion in the fight against Satan and le mal, he's also seen as something of a pin-up among the local community of nuns, who long to confess their every sordid thought and deed to him. Even in our heathen times, you can see how this might put him in a precarious position.

Moll has form with films of a committed strangeness - 2000's absurdist crime thriller Harry He's Here to Help, 2005's quasi-Buñuelian Lemming - but these films proceeded along more or less straight narrative lines. The Monk proves weirdly shapeless, chasing several other strands through its universe like a kitten after balls of string. Ambrosio's spiritual crisis coincides with the arrival of an apparently scarred youth hiding behind the spookiest mask seen on screen since Edith Scob in Eyes Without A Face; the courtship of a young woman (Joséphine Japy) in the nearby village; the attempts of a novice nun to hide both an affair and the resultant bellybump from the establishment, as represented by Geraldine Chaplin as "the Abbess"; the exorcism of a shepherd (a potential showstopper, thrown away in montage); and, perhaps not coincidentally, the passing of Ambrosio's mentor, who expires with the words "He's here! He's here!" on his lips.

The sound you can make out under all the electrical activity is that of deleted scenes hitting the cutting room floor, or of Moll and his co-writer Anne-Louise Trividic pulling their hair out trying to turn a heavily symbolic book - one that has eluded two previous sets of filmmakers - into coherent, or at least engaging, drama. The further the film gets away from Ambrosio's predicament, the more it takes on the look of robed soap opera, alternately silly and self-serious. Basically, it's The Thorn Birds with boobs, and while it makes sense to offer up the irresistibly ripe flesh of Déborah François by way of temptation, it seems unduly perverse to make the reliably hyperactive Cassel the stillest point on screen; we end up having to sit through an hour of the actor pretending to be virtuous in order to get to the lechery and lipsmacking we know he (and we) signed up for, and even that comes as disappointingly mild for the territory. Watching The Monk, you start to realise the movies may be missing Ken Russell more than they realise.

The Monk opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Tuesday, 24 April 2012

The yak-yak sisterhood: "Damsels in Distress"

This is a voice that may require some explanation for our younger readers. Between 1990 and 1998, the writer-director Whit Stillman turned out a run of smart, literate, most of all talky comedies centring on the personal and professional foibles of a group of young, recently graduated, generally affluent Americans. The films grew more expansive (and expensive) over time: from his low-budget breakthrough Metropolitan, Stillman (and many of the same characters and actors) progressed to the sunny Barcelona, part of a set of mid-90s American features (oft produced by the then-ascendant production company Castle Rock: Before Sunrise, Forget Paris) that sought to explore the New Europe. Stillman's crowning glory should have been the turn-of-the-80s period drama The Last Days of Disco, which had full studio backing (courtesy of Warner Bros.), up-and-coming young stars (in Kate Beckinsale and Chloe Sevigny) and a frankly fabulous soundtrack, yet still crashed and burned at the box-office, leading to a decade of stalled projects and despair for its creative force.

It may be another sign of the juvenilisation of the American cinema that Stillman has had to return with a college campus comedy, yet Damsels in Distress enjoys a surprising continuity with the world those earlier films were located in. You might choose to see it as Stillman's idea of an origin story: the movie that explains how his characters ended up where they did, in the state they were, saying the things that they said. "What's the plural of doofus?," one of his damsels wonders, to which her contemporary replies she thinks it might be "doofi" ("because it respects the Latin root") rather than the inelegant "doofuses". "You've thought a lot about this," Damsel #1 notes, which garners the response "I've had to". Stillman, you feel, has had to, too, and has had the time to do so: put plainly, there have been a lot more doofi about in the movies these past ten years.

The plot of Damsels in Distress owes something of a debt to such well-established sleepover faves as Clueless, Mean Girls, even The Craft. A new girl on campus, Lily (Analeigh Tipton), falls under the wing of a prevailing clique; in this instance, the demoiselles of Seven Oaks University's Suicide Prevention Center, a haughty trio who regard house parties as part of their outreach program and recommend dating losers (who can be molded into workable companions) rather than jocks (who smell bad, and will only break your heart). Sitting in judgement on their peers before a handpainted sign that bears the legend "Come on - it's not that bad", the Damsels feed the stressed and distressed free doughnuts in a bid to perk them up, although there remains a worry certain students have been pretending to be suicidal in order to get their mitts on free doughnuts.

Of course, it's the would-be sophisticates behind the desk who prove most in need of guidance, life-lessons, a wake-up call. After having her heart broken, de facto damsel-in-chief Violet (Greta Gerwig) goes off the rails - not in a LiLo way, but a very Whit-ty way, which is to say running off to nearby Villafranca and booking herself into a moderately priced motel. Violet, at least, has a plan for herself. Most of the characters surrounding her really are clueless, at least by the exacting intellectual standards Stillman sets. They don't know whether the name Xavier begins with an X or a Z (and have to concoct a counter-history for Zorro to make their thesis fit); they ask of Truffaut's 1968 film Baisers Volés "is it new?"; they pronounce everyday words ("fatigued", "operator") in an amusingly peculiar manner; one of the jocks hasn't yet gained any mental purchase on the concept of colour.

You could argue that Stillman is being frightfully condescending around these not-so-bright young things, but he rather likes their company, even as they allow him plentiful opportunity to skewer the delusions and hypocrisies of youth. (This may explain why he's been persona non grata with producers, who nowadays would much rather pander to our kids than dare say anything about them.) Violet insists "we are all flawed - must that render us mute to the flaws of others?" Her would-be love interest Charlie (Adam Brody) defends himself at one point with the impressively semantic "I wasn't lying - I was making it up!" Both characters have taken steps to reinvent themselves in the timeless quest for popularity and happiness: Violet, we learn, was born Emily Tweeter, while Brody's character was formerly known as Fred Packensacker, names over which the spirit of Preston Sturges surely presides.

Stillman, too, is trying to reinvent himself as a commercially viable filmmaker, yet certain aspects of his personality remain fundamentally unaltered. His logorrhea shows precisely no signs of abating: the new film has long, considered riffs on such topics as the importance of scented soap to a good life and man's inexplicable emotional attachment to the hackysack, as well as several of the subtlest allusions to anal sex ever made in a 12A-rated movie. Like his closest French counterpart Eric Rohmer, Stillman believes that character is best revealed through talk; he treats words as one might the family's best silver cutlery, polishing them endlessly. It should be noted there is a lot in Stillman's cutlery drawer: Damsels in Distress throws up only just fewer more words-per-minute than Aaron Sorkin, and I can understand why several esteemed colleagues of mine found the experience akin to being buried under an avalanche of arch, arcane chatter. (I'll confess I've always found Stillman's films more pleasurable on a second or third viewing, by which point the construction and characters have started to emerge from the more verbose passages.)

Still, the approach has its advantages. Minor characters and day players (here extending to the calibre of Arrested Development's Alia Shawkat and Funny People's Aubrey Plaza) get whole paragraphs and monologues to themselves, and it gives a quartet of very appealing young actresses the kind of lines and ideas to play with that they're unlikely to get in the multiplex romantic comedies that might be lurking in wait for them two or three years down the line. Gerwig, the mumblecore postergirl whose support for the script apparently helped get the film greenlit, is rewarded for her loyalty with a lavish tap-dancing number that expands some way beyond Disco's mirrorball scenes, but the film also grants major career boosts to her fellow damsels: Tipton, proof you can graduate from America's Next Top Model and still appear smart, funny and judicious in your choices; Carrie MacLemore, in what we might call the Amanda Seyfried role as the sort of sweetly, breathlessly dumb young woman only a truly intelligent performer might keep from toppling over into outright caricature; and Megalyn Echikunwoke, blessed with the irresistible combo of a plummy English accent and perfect timing, whose riffs on "playboy-slash-operat-or type behaviour" may just be the funniest thing here.

I say may, because Stillman clearly remains a matter of personal taste. Somewhere within Damsels, there lurks the suspicion the director may be faking the kind of gaucherie the movies lap up nowadays; it rears its head most obviously in the closing moments, when he gives Tipton a big assimilation speech damning the cult of cool, and stressing that the uniqueness we prize in others too often manifests itself in the form of colossal pains in the neck. "What we need," our heroine concludes, "is a large mass of normal people" - and Damsels in Distress, which ends with an attempt to start a dance craze and a rainbow in the sky, may just be the closest Stillman comes to making a "normal" film without selling out altogether. We can hardly blame an indie filmmaker for wanting to come in from the cold, though, and this sundappled opus at the very least returns to circulation a voice that, in its gender balance and rarefied vocabulary, provides a welcome alternative to the relentless knob gags of so much mainstream comedy. Nobody else working in 2012 would have one of their college-age characters ask, in all apparent seriousness, "you've entirely dropped your allegiance to the Cathar faith?" - even if they are alluding to sodomy.

Damsels in Distress opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Monday, 23 April 2012

Red-handed: "Being Elmo: A Puppeteer's Journey"

Back when I was just young enough to be watching Sesame Street, the star attractions were Big Bird, Oscar the Grouch, and Bert and Ernie. No-one back then had even heard of Elmo, let alone thought that he might spawn spin-off movies and the most sought-after merchandise of several consecutive festive seasons - and in doing so generate money in numbers beyond even the Count's wildest dreams. Elmo, an impulsive, affectionate red-furred critter with ping-pong balls for eyes, became so adored so quickly that it's tempting to label him the Ryan Gosling of the Children's Television Workshop: the cloth cut who seemingly came out of nowhere to throw his arms around the world.

Constance Marks' new documentary Being Elmo, narrated by Whoopi Goldberg, profiles both the phenomenon and the man who provides Elmo with his anima and his instantly recognisable high-pitched voice. The stocky, fortysomething Kevin Clash grew up in an underfunded black neighborhood in the back-end of Baltimore, the city now firmly established as the cradle of American cultural diversity: giving rise to Elmo, Omar Little and the movie career of Divine will stick a place with that reputation. But this is Elmo's story, too: a character first tested out by the husky Richard Hunt - the surviving

footage is startling, like watching Kristin Chenoweth

opening her mouth to sing like Barry White - only to be consigned to the Sesame Street stock cupboard. The backstage drama here is how Clash, after a decade of jobbing puppetry both within and without the Henson empire (Captain Kangaroo, Labyrinth, the long-forgotten The Great Space Coaster), was motivated during one career lull to remove Elmo from mothballs, and thus create something in its own way revolutionary. It's the story of a creative belatedly coming to find his perfect partner, and - through them - the voice that would speak to millions.

Puppetry is an old-fashioned medium, and it's old-fashioned virtues the film accordingly seeks to enshrine: unconditional love and extraordinary belief. Painstakingly hand-sewed (a cashmere coat belonging to Clash's pop takes a hit in a formative anecdote), the puppeteer's creations are stitched with the exact same affection as Aardman's plasticine figurines, and similarly motivated: less out of a desire to get rich quick (Clash only inherited Elmo in his thirties) than a need to get every last gesture right. Clearly, the illusory nature of television - the selective camera angles, the choice editing - can aid the puppeteer, but what's astonishing (and very touching) here is how children react even when Clash is in the room with Elmo, working the magic that obliges them to overlook the presence of his hand around the puppet's nether regions, or to assume he must be Elmo's PA, helper or father. Part of the puppeteer's artform, you realise, is making themselves disappear, becoming a mere observer, and Clash's curiosity - not just around mechanics, but people, too - evidently factors into Elmo's own personality.

As a boy, Clash sat with his nose to the TV screen, gawping at Sesame Street (whose diversity made it the closest thing he could find on the box to his own neighborhood) and later The Muppet Show, trying to figure out how such tricks were performed; his current work is, as he reveals, informed by that which he observes about his fellow humans, such as the way we nod our heads, subtly yet frequently, while listening to one another - the kind of minor detail that, when layered into a routine, can transform Elmo from the merely cuddly to the credible: a friend and companion. The reason millions raced to buy Tickle-Me Elmo dolls was because they bought Elmo, and the values he represents, absolutely: there are, sadly, too few human entertainers who merit that level of trust. I remain, first and foremost, a devotee of the Cookie Monster, whose needs and desires are recognisable to grown-ups as well as kids and hypoglycemic inbetweeners like myself, but - in an age of crushing, often predatory mass-media cynicism - it's good to know our young can still be placed in such safe and skilful hands as Clash's. Elmo is empathy, and this is a great big hug of a film.

Being Elmo: A Puppeteer's Journey opens in selected cinemas from Friday.

Attack forces: "The Assault"

On Christmas Eve 1994, a quartet of young Muslims with ties to the extremist group GIA boarded an Air France flight in Algiers. Disguised as presidential policemen, they promptly took all 172 passengers and crew hostage. The faction's stated aim was to secure the release of two political prisoners - though there were equally claims made at the time that the hijackers intended to fly the plane into a major Parisian landmark. The Assault, writer-director Julien Leclerq's no-nonsense, straight-ahead reconstruction of these events, follows the official response along two lines: that of Carole Jeanton (Mélanie Bernier), a foreign ministry worker in Paris who'd collated intelligence on the GIA, and that of the special forces team sent to assemble at an airfield in Marseille, where the plane would eventually be due to refuel.

With its washed-out colour palette, jittery camerawork and cast of largely unknown (thus expendable) faces, the style is what we have now to describe as knock-off Greengrass. Yet where, in the British director's United 93, we knew exactly how the story would be resolved, The Assault both suffers and benefits from non-French viewers' unfamiliarity with these events. There are a lot of indecipherable acronyms flying around: the GIGN, the DGSE, the FIS; there's even mention of something referred to as The Chrysanthemum Operation, which we may have to get Alan Titchmarsh in to brief us on. On the plus side, the film unfolds as a genuinely tense experience for those of us without prior knowledge of the story, particularly when the plane finally receives clearance to take off, heading one cannot be sure where, and later approaches Marseille, with the snipers lined up in residence.

Leclerq marshals his hardware - the guns, the planes, the Pumas - with some skill; he's good on the aircraft's confined space, managing to pin down the exact position of his characters within the cramped cockpit during the final push, here less of a clear-cut "let's roll" moment than a bloody war of attrition. If there's a weakness, it's that the strict adherence to procedural norms leaves the characters barely less developed than you'd get from a newspaper account of the stand-off; these figures often seem less like people than pieces to be pushed around a table top, or pins being pushed into a map. (United 93 had something of the same problem, arguably.) Jeanton, for one, is rather too obviously conceived as a movie archetype (lone dame working within an all-male institution), there to have her suggestions shushed by the GIGN committee, or be ticked off whenever she attempts to take charge.

Similarly, while special forces leader Thierry (Vincent Elbaz) is meant to be suffering some kind of trauma as a result of a botched operation, it's left naggingly unclear what he's supposed to have done in the rushed-through prologue. The terrorists, for their part, are allowed their prayer rituals, and some acknowledgement of their strength of faith ("If this goes on for a year, we'll be here for a year"), but keep being contrasted, rather too simplistically, with the idyllic family life Thierry enjoys with his blonde wife and super-cute daughter. (In one of those you-couldn't-make-it-up moments, one hijacker seizes the impasse as an opportunity to propose marriage to one of the female passengers.) It all grips like a vice, but a little more sensitivity - some greater understanding of what it is to make a film about the actions of extremist groups in this day and age - wouldn't have gone amiss; as it is, like its muddle-headed special-ops hero, The Assault storms in, paying little heed to the possible consequences of its (admittedly well-staged) action.

The Assault opens at the Institut Français in South Kensington today.

Friday, 20 April 2012

For what it's worth...

Top Ten Films at the UK Box Office

for the weekend of April 13-15, 2012:

1 (new) Battleship (12A) **

2 (1) Titanic (12A) ***

3 (new) The Cabin in the Woods (15) ***

4 (2) The Hunger Games (12A) **

5 (4) The Pirates! In An Adventure with Scientists! (U) ****

6 (3) Mirror Mirror (PG)

7 (6) 21 Jump Street (15) **

8 (5) Wrath of the Titans (12A)

9 (8) The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (12A) **

10 (9) StreetDance 2 (PG)

(source: guardian.co.uk)

My top five:

1. Beauty

3. Breathing

4. The Assault

5. Gone

Top Ten DVD rentals:

1 (new) Contagion (12) ***

2 (8) Hugo (PG) ***

3 (2) The Help (12) ***

4 (3) In Time (12) ***

5 (4) My Week with Marilyn (15) ***

6 (new) Moneyball (12) ****

7 (9) The Ides of March (15) **

8 (5) The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn (PG) **

9 (re) Midnight in Paris (12) ***

10 (1) Puss in Boots (U)

(source: lovefilm.com)

My top five:

4. The Future

1. One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest [above] (Saturday, BBC2, 9.55pm)

2. The Magnificent Seven (Sunday, five, 6.30pm)

3. The African Queen (Monday, C4, 1.10pm)

4. Beetlejuice (Saturday, five, 5.30pm)

5. The Italian Job (Saturday, C4, 6.20pm)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)