Monday, 28 February 2022

Balls of steel: "Jackass Forever"

Saturday, 26 February 2022

For what it's worth...

My top five:

1. Annette

1. The Apartment (Saturday, BBC2, 1pm)

Friday, 18 February 2022

For what it's worth...

My top five:

1. Annette

1. Notting Hill [above] (Saturday, ITV, 10.40pm)

Thursday, 17 February 2022

In memoriam: Douglas Trumbull (Telegraph 16/02/22)

Movie magic was a

Trumbull family business. His father Donald had been a technician in Hollywood’s

Golden Age, rigging the flying monkeys on The Wizard of Oz (1939); in

his later years, Trumbull Sr. won two technical Oscars for his innovations in

the fields of matte photography and motion-control camera systems.

His son landed his big

break assisting on To the Moon and Beyond (1964), a 15-minute short produced

by Graphic Films for the World’s Fair that zoomed out from a sub-atomic view to

observe the Earth from space. Among its admirers was Stanley Kubrick, who flew

Trumbull to London, initially to provide animations for 2001’s computer

monitors.

Quick to earn his

famously circumspect employer’s trust, Trumbull assumed additional

responsibilities as production wore on: “He would say, ‘What do you need?’ and

I’d say, ‘Well, I need to go into town and buy some weird bearings and some

stuff’ and he would send me off in his Bentley, with a driver, into London. It

was great!”

It was a new frontier, in

every sense: as Trumbull put it, “We wanted the audience to feel like they were

actually going into space.” Yet creative freedoms were tempered by Kubrickian

control; the two men fell out after the director assumed sole onscreen credit

for the film’s Oscar-winning effects, with Trumbull vowing to work independently

in future.

His freelance career

began inauspiciously. Trumbull underbid for the effects work on Universal’s The

Andromeda Strain (1971), leaving him with only $250,000 to generate the microscope-like

close-ups of the titular virus. A distribution quirk saw that film jettisoned

on an underpromoted double-bill with Trumbull’s directorial debut Silent

Running (1972), an unusually emotive, eco-themed sci-fi about a lone

scientist (Bruce Dern) tending plantlife on a spaceship orbiting a dying Earth.

Completed for a tenth of 2001’s

budget, Silent Running allowed Trumbull to finesse a sequence involving

Saturn’s rings originally visualised for 2001, but elsewhere the modest

resources compelled him to improvise. College students – including future

effects whizz John Dykstra – were hired to suppress costs, many set to

assembling the 650 tank modelling kits used in the film’s miniature shots.

Though a commercial flop,

Silent Running proved hugely influential on those who saw it. George

Lucas approached Trumbull to work on Star Wars (1977); Trumbull turned

the offer down, while approving Lucas’s plan to model the droid R2-D2 on Silent

Running’s expressive drones Huey, Dewey and Louie. (Both Trumbull Sr. and

Dykstra would work on Star Wars in various capacities.)

By that point, Trumbull

was busy elsewhere, having been appointed VFX supervisor on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). This was an especially demanding production, entailing

200 effects shots that needed to inspire awe while meshing with Steven

Spielberg’s completed live-action footage. Yet Trumbull found practical

solutions to the film’s challenges: the ominous cloudscapes signalling the

aliens’ arrival were formed by filling fish tanks with saltwater and paint. It earned

him a first Oscar nomination, losing – in a field of two – to Star Wars.

Visual effects ingenuity sometimes

resembles elevated child’s play, yet Trumbull’s experience on Star Trek: The

Motion Picture (1979) was hard labour. Belatedly hired after another

effects house failed to bring the U.S.S. Enterprise to cinematic life, Trumbull

worked overtime so the film could hit its planned Christmas release date; it landed

him a second Oscar nod, plus ten days in hospital with an ulcerated stomach.

Upon recovery, Trumbull

was lured back to hired-hand work on Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982).

Drawn by the prospect of detailing a careworn Earth rather than something stratospheric,

he contributed several elements to the stunning opening panorama, including the

images projected onto skyscrapers and the refinery flames, recycled from

explosions Trumbull had filmed for Zabriskie Point (1970).

That worldbuilding was

again Oscar nominated, again unsuccessful, but by then he was directing once

more. Trumbull initially conceived the psychological thriller Brainstorm

(1983) as a showcase for a new, high-definition photography process known as

Showscan. When studio MGM balked at the cost, Trumbull ploughed on, only for

the project to be comprehensively derailed when star Natalie Wood drowned in

mysterious circumstances mid-shoot.

Studio bosses wanted to halt

production and claim the insurance, but Trumbull persevered, recruiting Wood’s

sister Lana as a stand-in for the remaining shots. That there was anything

releasable was some achievement, but reviews were middling and box-office tepid,

sending Trumbull into retreat: “I just had to stop. I had been a

writer-director all my life, and I decided it wasn’t for me because I was put

through a really challenging personal experience… I decided to leave the movie

business.”

Douglas Huntley Trumbull

was born in Los Angeles on April 8, 1942 to Donald Trumbull and Marcia Hunt, a

commercial artist. A tinkerer from an early age, young Douglas built

crystal-set radios and soaked up science-fiction movies; he studied

illustration at El Camino College with the aim of becoming an architect,

joining Graphic Films upon graduation, where he also worked on promotional

films for the Air Force and NASA.

In later life, Trumbull

moved to Massachusetts and into the less pressurised field of motion simulators

and theme park attractions, most prominently directing a short film for the Back to the Future ride at Universal Studios Florida, launched in 1991. He won a

technical Oscar in 1993, for his work in the development of a new 65mm camera,

and was appointed vice-chair of IMAX in the mid-1990s, as the corporation

expanded worldwide.

In 2011, he pulled the

old magic tricks out of retirement, photographing chemical reactions in petri

dishes and injecting paint into water tanks for the eyepopping Creation of the

Universe sequence in Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life: “It was a

working environment that’s almost impossible to come by these days… Terry

wanted to create the opportunity for the unexpected to occur before the camera.”

He continued tinkering, going

viral in 2010 with a video that proposed a solution to the BP oil spill, and offering

his Magi Pod, an immersive boutique cinema, as a cure for the modern

multiplex’s projection ills. He won the Tesla Award in 2011, and an honorary

Oscar in 2012. Thereafter he was an avuncular presence on the convention

circuit, embracing fans beguiled by a groundbreaking legacy: “They reinforce

some enthusiasm about my work. It’s very hard to keep me going, because the

setbacks were really tragic and difficult.”

He is survived by his

third wife Julia Trumbull (née Hobart), and by Amy and Andromeda, two

daughters by his first wife Cherry Foster; his second wife, Ann Vidor, died in

2001.

Douglas Trumbull, born April 8 1942, died February 7 2022.

Tuesday, 15 February 2022

On demand: "Cow"

Friday, 11 February 2022

For what it's worth...

My top five:

1. Annette

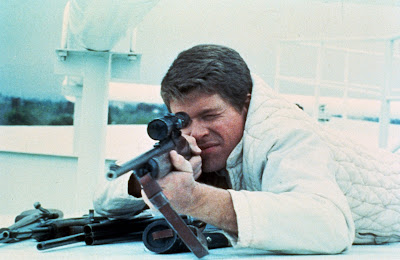

1. The Conversation (Saturday, BBC2, 1am)

On demand: "Targets"

Monday, 7 February 2022

Drawing it out: "Flee"

Friday, 4 February 2022

For what it's worth...

My top five:

1. Annette

1. Collateral [above] (Saturday, ITV, 10.35pm)

My streaming gem: "Karnan" (Guardian 04/02/22)

The film's first half, however, serves chiefly to define its warrior-in-chief – and thus to demonstrate that appearances can prove deceptive. Karnan initially presents as a nice lad with sensible hair, ticking the first box of Indian movie heroism by being good to his put-upon mother (Janaki). Yet the characterisation is soon complicated. A drinker and a gambler, Karnan is less your typical masala maverick than a punk-in-waiting. He’s a hothead who spends this first hour getting into scraps, pushing away the one gal who’s crazy about him, and – in a pre-intermission sequence that must have been tremendous fun to shoot – singlehandedly trashing one of those rackety old buses pootling between backwaters. (He does much the same to a police station just after the break.)

This is a kid with fire in his belly – that’s what makes him such a hothead – yet while Selvaraj grasps these flames can be destructive, he also knows that in certain cases they’re exactly what’s required to effectuate real and lasting change. Sometimes, the movie posits, you have to burn down the whole rotten system and start again from scratch. The blazingly unpredictable hero is one reason Karnan emerges as such an unpredictable watch – it’s a morality play hitched to a genuine loose cannon. In the course of the film, Karnan will alienate family members and the wider village; at points, all we can cling to is the knowledge our boy seems unlikely ever to take the shit the penniless farmers around him have been forced to swallow for generations.

Somewhere in the mix, there’s a standard-issue crowdpleaser: you glimpse it whenever Dhanush raises himself up to his full 5’5” (5’4½”, when wet) and sets about righting this world’s wrongs – wealth inequality, police brutality – to what you suspect would have been huge cheers from the cheap seats had the film’s theatrical run not been curtailed by Covid. But it’s been overlaid by an artistry and delicacy rarely observed in films of this scale: if not the full Rajamouli, then not a hundred miles away. Cinematographer Theni Eswar provides lustrous cutaways to the region’s flora and fauna. And his overhead shots are positively sculptural: men gathering in a field mowed to resemble a bull, lovers trysting by a heart-shaped pond.

The worldbuilding is elevated to the point where it begins to resemble cosmology, yet as we look upon this busy, tempestuous, hotly contested few acres of land, we realise it’s not so far removed from our own backyards. It could do with more lady in its lake, true: where the Baahubalis offered equal-opportunity mythos, the women here fall between spectators and damsels-in-distress. (It’s a Dhanush film, and some hierarchies may be harder to topple than others.) Yet Selvaraj makes enough genuinely bold, even radical choices elsewhere, not least amid the tense siege finale, to make one regret that Karnan got shuttled off to streaming mid-pandemic. This is a film that takes up a small, everyday struggle, then rides hell-for-leather to fill the screen entire with it.