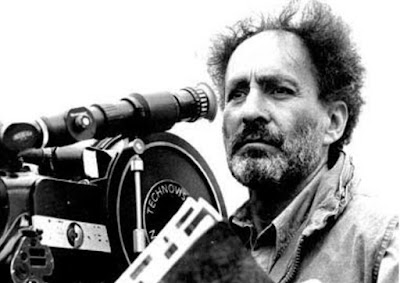

Monte Hellman, who has died aged 91, was a writer-director working on Hollywood’s fringes who achieved semi-legendary status among cinephiles, in part due to a filmography consisting almost exclusively of cult items.

The most notable of these

was Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), an anti-road movie that crystallised

American anomie at the moment of Vietnam. Backed by Universal to replicate Easy

Rider’s success, the finished feature proved perverse indeed. Its cross-country

drag race proposed that speeding could be as enervating as sitting still; the inexperienced

leads, singer James Taylor and Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson, gave muted

performances.

After studio chief Lew

Wasserman pulled all promotion, decrying the film as “subversive”, it fell into

obscurity, and remains contentious: David Thomson damns it as “elliptical,

oblique and equivocal, marred by its own lofty intransigence toward audiences”.

Yet these were precisely the qualities that led buffs to rediscover and treasure

it, and its critique of American mythmaking went far beyond Easy Rider: its

big finish was the film stock burning up before our eyes.

That high-profile

flameout prompted a fallow period, although Hellman returned to prominence two

decades later when longtime fan Quentin Tarantino sought his opinion on the

script for Reservoir Dogs (1992). Noting how keen the younger man was to

direct, Hellman assumed executive producer duties, fundraising the launchpad

for one of modern American cinema’s most prominent careers.

In doing so, Hellman

bridged two generations of indie filmmakers, but he surely observed the rise of

Tarantino, a fellow iconoclast handed ever greater resources, with conflicting

emotions. Reviewing his own fitful progress, he sighed: “When I was selling

Eskimo Pies in Hollywood as a teenager, my dream was to have my own parking

space in any studio... My problem has always been that I’ve had my little

parking space, but I was never in a studio long enough to have my name painted

on one.”

He was born Monte Jay

Himmelbaum on July 12, 1929, in Brooklyn, where his parents – grocer Fred and wife

Gertrude (née Edelstein) – were visiting. The family relocated to the

West Coast, where young Monte attended Los Angeles High; he studied drama at

Stanford and film at UCLA before being taken on by ABC as an editor’s

apprentice.

Initially, Hellman gravitated

towards the theatre: forming his own company, he staged the first L.A.

production of Waiting for Godot, with funding from the emergent

benefactor Roger Corman. (Hellman later asserted “there is a little bit of Beckett

in everything I’ve done”.)

After the theatre closed,

he joined Corman’s industrious film arm. His directorial debut was Beast from

Haunted Cave (1959), a creaky mash-up of crime thriller and monster movie, but

his most distinctive Corman works were two Westerns starring a pre-fame Jack

Nicholson, The Shooting and Ride into the Whirlwind (both 1966).

Shot back-to-back in the

Utah desert for a total of $150,000, these became thoughtful parables of

existentialism. “We thought they would be a couple more Roger Corman movies

that would play on the second half of a double-bill,” the director confessed. “We

never thought anybody would ever notice.” Cahiers du Cinéma did, listing

Ride among its ten best of 1968.

After Two-Lane

Blacktop’s commercial failure and the further bodyblow of being replaced by

Sam Peckinpah on Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), Hellman returned

to Corman’s orbit to make Cockfighter (1974), an unsparing adaptation of

Charles Willeford’s crime novel.

Though vividly lensed by

the great Nestor Almendros, the project stumped the marketing men; even

reissued as Born to Kill, it became the first film in the history of

Corman’s famously frugal New World Pictures to lose money. It remains largely

out of circulation, partly due to unsimulated scenes of animal cruelty.

The paella Western China

9, Liberty 37 (1978) proved more saleable, but Hellman was briefly reduced

to undertaking work-for-hire. He finished up two projects – Muhammad Ali biopic

The Greatest (1977) and spy thriller Avalanche Express (1979) –

after their directors died mid-shoot; he shot second unit footage for Robocop

(1987).

Iguana (1988) was at least a Hellman original, an

eccentric meditation on power about a disfigured harpooner who appoints himself

king of a remote island, though the director himself dismissed it as

“terrible”. It became a prize for Hellman cultists, though, as did Silent

Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out! (1989), an instalment of the

Yuletide-themed horror franchise written, shot and released inside four months.

Yet with Tarantino’s

patronage, Hellman’s profile began to rise anew. He was invited to join the

Academy in 2007, becoming an enthusiastic member of the Oscars’ foreign-language

film committee, and in 2010 he completed his final feature Road to Nowhere,

a brooding study of a filmmaker going rogue while on location.

Following the film’s

Venice premiere, its maker was handed a lifetime achievement award by

Tarantino, who lauded Hellman as “a great cinematic artist and a minimalist

poet”. While clearly personal, the film opened to familiarly mixed reviews: Variety

called it “a twin peak” to Two-Lane Blacktop, while The New Yorker

dismissed it as “a dead end”.

In recent years,

Hellman’s primary income came from renting out a room in his Hollywood Hills residence

via Airbnb. Interviewed at home in late 2020, he concluded his career “was

sporadic, but it was fine”.

He married and divorced three

times; he is survived by Melissa and Jared, his children by his second wife

Jaclyn Hellman.

Monte Hellman, born July 12, 1929, died April 20, 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment