Garrett Bradley's documentary Time opens with home-video footage of a young, heavily pregnant Black resident of New Orleans directly addressing the camera, and assuring the viewer that everything will turn out all right for her. Flashforward twenty years, and we find the same woman surrounded by kids and emboldened by the success bestowed upon her via a career as a motivational speaker and activist. The woman is Sibil Richardson, known professionally as Fox Rich, and to some degree, things clearly have turned out all right for her. Yet it's taken time, and what reality-TV contestants are fond of referring to as a journey, and some of that time has, in fact, been hard time: those home videos, we learn, were being recorded for the benefit of a husband, Rob, sentenced to 60 years behind bars for his part in an armed robbery. Sibil herself drove Rob there, and was sentenced to twelve years as an accessory; she's spent the years since her (early) release appealing her husband's sentence, which means navigating the byzantine corridors of the U.S. criminal justice system day after day. It's made for a long wait, all in all, and Bradley has ways of allowing us to feel the time. In a sharp sequence early on, we find Sibil phoning the County Clerk's office to hear Rob's latest appeal result, only to be put on hold; Bradley keeps filming, knowing full well the next time this woman hears a human voice, it will determine whether or not a wife can be reunited with her husband, boys with a father. If you find that extended pause excruciating, be thankful you're only eavesdropping.

So this is a film with time on its hands, to shape as it will. Some of Time's 81 minutes are spent watching those boys grow up, as Sibil herself has: Bradley shows us that the little cherubs in that video footage - to which the film returns from time to time, filling knowledge gaps, merging present and past - have, under their mother's eye, matured into nurturing, self-improving young gentlemen. (One's a dentist, another's making confident strides into the arena of student politics.) Mostly, Bradley's engaged in a process of quiet observation. She spies the everyday tenacity, patience and strength Sibil has to summon to get herself over the next round of challenges, but also the pronounced gap between his subject's polished public persona, schooling her fellow prison widows on how to tear down those walls ("I'm an abolitionist"), and how it is when it's just her and the camera, and she begins to let down her own defences. In these moments, the forceful influencer wielding a microphone like a horn of Jericho recedes, replaced by an ever so slightly tired middle-aged woman who can barely find the words she needs to express herself. There are points where it appears as if we've been brought this way to observe a personality split in two: Sibil is a mother and wife setting out into the world to make a life for herself and her boys, but she's also clearly left some part of herself behind bars with the man she loves. It's as though she had to invent the persona of Fox Rich, seen tersely repeating the mantra "success is the best revenge", to psych the very real, far more vulnerable Sibil Richardson up.

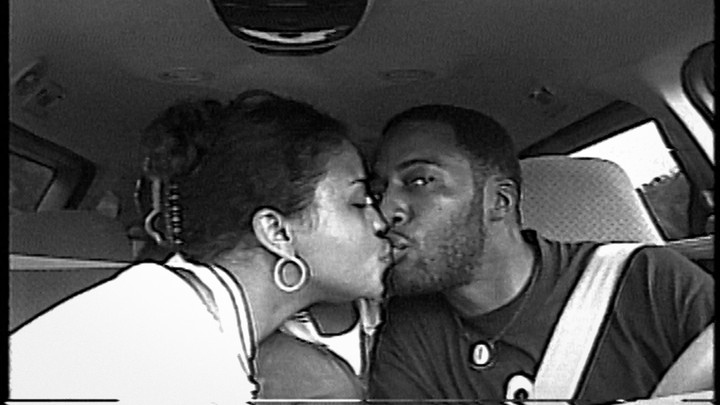

As a film, Time creeps up on you, and that's down to how much it wrings from scenes of humdrum ordinary life - from simply being around someone and keeping eyes and ears open. Bradley proves a master of the lingering close-up: she trains her camera on Sibil at work, church, graduation ceremonies or burning off some of her frustrations at the gym, assured that her careful framing - that choice sampling of camcorder footage to outline this woman's past - has clued us into what might be on her mind, or weighing on her shoulders. (And not just her mind and shoulders: another sequence finds her youngest boy at school, being lectured about the prison system. In this instance, a pupil might have more of note to say than his teacher.) The monochrome with which Bradley matches the home video gives Time an instantly poetic quality: it renders these lives timeless. Ignore the cellphones that pop into frame, and note the Christianity that serves as both a holdover and something to cling onto, and Bradley's film could be happening at just about any point in the past one hundred years. Which serves as its own damning indictment of the arthritic nature of American justice, so quick to condemn, so slow to forgive, or even to process: if the arc of history bends here, it does so almost imperceptibly. Still, sit tight, for there is the ending, which justifies all the waiting and fulfils the prophecy of those first frames, while leaving a stark caveat behind in its wake: that Sibil's is but one story among many, and that many of those won't have happy endings - indeed, they'll have no ending at all.

Time is now playing at the Everyman King's Cross in London, and streaming via Prime Video.

No comments:

Post a Comment