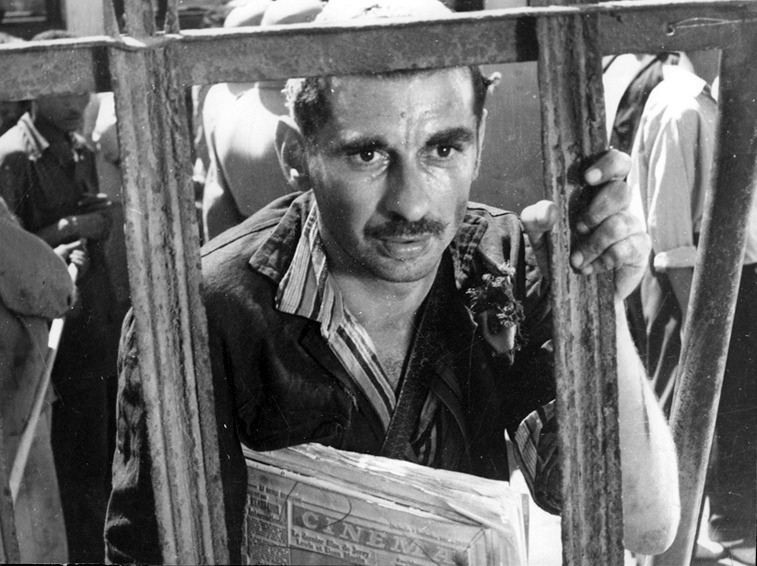

Egyptian cinema's international breakthrough Cairo Station - one of a dozen Youssef Chahine titles to have reached Netflix this month - approaches the venerable old transport hub enshrined in its title as a living, breathing ecosystem, much like the hotel in Grand Hotel. All human life as it must have been in the Cairo of 1958 is here: commuters, vendors, hepcats, restless workers, unyielding management, plus a reported killer for good measure. The one element who doesn't obviously fit into this panorama is the hobbling, bobble-hatted vagrant Qinawi, who's developed an obsession with one of the vendors (local goddess Hind Rostom, dubbed the Arabian Marilyn Monroe) and has taken to lining the walls of the corrugated iron shack he's claimed as makeshift housing with pin-ups he's snuck off with from his day job as a cross-platform paperboy. In an enduring note of self-criticism, this solitary oddball - forever popping up at windows, peeping in on a world that doesn't much want him, and which he can barely even begin to understand - is played by the director himself. On many other fronts, however, Chahine was doing perfectly fine.

One reason the film travelled beyond local borders, you soon realise, was its uncoupled expressivity: once set in motion, the project simply couldn't be contained. Thinking substantially bigger than his peers, Chahine fills the screen with abundant characters, declamative performances that possibly owe more to Bollywood than Hollywood (or, likelier still, a pre-existing Egyptian acting style) and an unabashed lustiness that remains striking this far into the 21st century. Qinawi's pin-ups are but a mild serving of cheesecake, but a scene highlighting the voluptuous Rostom in a diaphanous underskirt would probably have cued censorial conniptions the world over in 1958. It's not a subtle film, then - in several places, characters (and actors) step out in front of locomotives exiting sidings at a fair old clip - but Chahine seemed to realise, from this very early stage in his career, that the most resonant cinema often isn't. His close-ups loom out at us; his imagery is bold and unapologetically blatant. Take the cut from Qinawi peeping on his beloved's tryst with another man to an insert of a departing train's wheels flattening down a loose stretch of track: if you can't understand how this guy feels from that, then your career in film studies may have to terminate here. I spied a particular correlation between Cairo Station and those Eastern masala movies juggling six different narratives and modes simultaneously, though other influences are equally visible: you sense Chahine planting two feet square in the middle of the 20th century and striving to synthesise everything that had come before him (old-school glamour, a dash of neo-realism) with everything that was going on around him at the time. The film that emerges from this process is - somewhat amazingly - only 77 minutes in duration, but it's one heck of a marker, a point from which an emergent creative could travel in any number of directions, and an offshoot of a cinema that already contained, and sometimes struggled to contain, multitudes.

Cairo Station is one of twelve Chahine titles now streaming on Netflix; details of the others can be found here.

No comments:

Post a Comment