Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 cyberpunk opus Ghost in the Shell, one of the first Japanese anime titles to cross

over to Western audiences, has been reissued and repackaged so often since the

millennium that it’s scant surprise studio execs seized upon it as reproducible

property. Possibly it was a matter of waiting: for digital effects houses to

get up to spec, the right deals to be struck, and any accusations of cultural

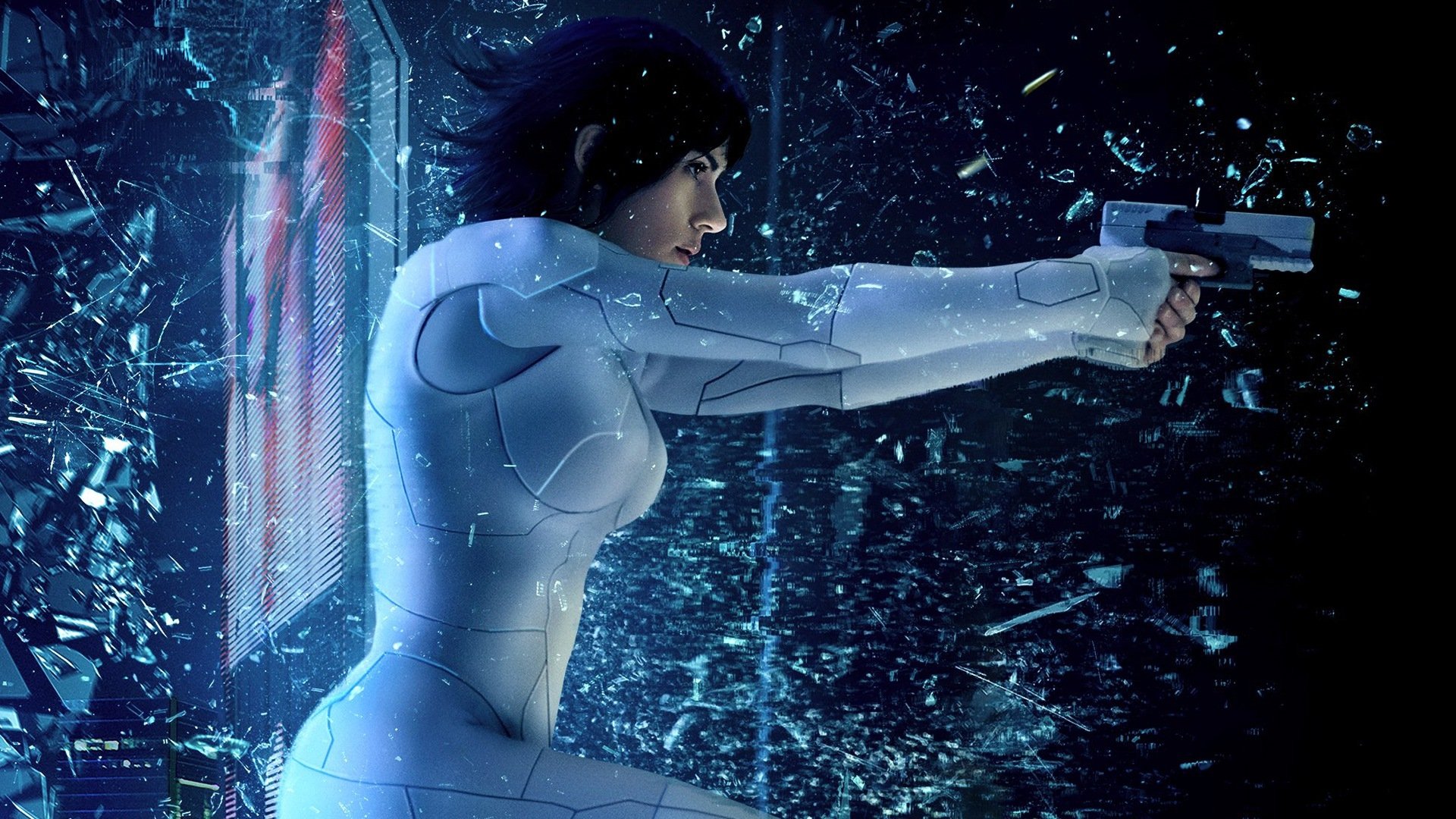

appropriation to blow over. Paramount’s all-new live-action Ghost, powered by hefty reserves of

American and Far Eastern money, emerges as a dazzling logistical display with a

missing file where the human interest might once have been stored.

Fans need not blubber unduly: as overseen by Snow White and the Huntsman’s Rupert Sanders,

this transliteration would seem faithful enough to satiate those who just want

to see favourite scenes and characters redrawn on the biggest screen

imaginable. As that suggests, what’s been tinkered with is the scale: Oshii’s

knotty postmodern inquiries into identity – a stopover on that fin-de-siècle

sci-fi continuum connecting Blade Runner

to The Matrix – are here stretched

into IMAX-ready, 3D-enabled spectacle. Blown up to this magnitude, ideas

already threadbare through twenty years of recycling start to look doubly thin.

Narratively, there’s little to separate the two movies. Again,

we open on the creation of a cyborg – Scarlett Johansson’s Major, being a human

brain, retrieved in the wake of a fatal accident, set lovingly in a

slinky-dinky metal-plastic carapace – who evolves to exist at the mercy of

multiple masters. There’s the counterterrorism chief (Takeshi Kitano) who dispatches

her to investigate a series of assassinations; the female engineer (Juliette

Binoche, slumming elegantly) who nurtures her and patches her up; and her corporate

manufacturers – embodied by Peter Ferdinando’s brooding Mr. Cutter – who regard

her as no more than an asset on a spreadsheet.

More compelling than any of these figures, however, is the

realm they pass through. The flawed but glitzy Snow White rehash positioned Sanders as a facilitator of lavishly

visualised if faintly derivative worlds; armed here with both the latest

modelling software and several skilled analogue collaborators – production

designer Jan Roelfs (Gattaca), emergent

cinematographer Jess Hall (Transcendence)

– he goes into hyperdrive. Every scene thrusts out something to catch (and

occasionally caress) the eye: murky drinking dens besieged by scuttling,

arachnoid attendants, a watery virtual limbo where binary ones and zeroes float

up like bubbles.

So yes, it’s the shiniest of kit; whether the emotions are

stirred is another matter. Johansson sets the level of engagement, by playing

the impervious shell rather better than she does the restless ghost. In 2013’s

unsettling Under the Skin, the

actress was directed into signalling a hybrid’s dawning consciousness (and

conscience); here, she’s limited to looking puzzled while convoluted plot stuff

streams around her. The time Johansson has logged among the Avengers means she

could perform the role’s asskicking aspects in her sleep – but in so many other

scenes, she appears to be on autopilot: left to execute commands, rather than

encouraged to flesh this part out.

Supporting players are defined chiefly by their hairstyles. Snowtown ne’er-do-well Daniel Henshall

models a mullet that identifies him as an individual of questionable judgement;

Major’s sidekick Pilou Asbaek sports a shock of white fluff that might work for

manga heroes but turns grown men into Billy Idol tribute acts. As his

explosion-blackened corneas are replaced with ophthalmic lenses, you sense a

rampant techno-decorousness beginning to consume the performers – a instinct

compounded upon seeing Buddhist monks plugged into a towering cable router

redolent of Avatar’s Tree of Life.

Like much else here, it’s striking but second-hand.

That last image has presumably been designed to chime with a

moment when even the Dalai Lama delivers his wisdom in 140-character bytes, yet

– like the allusions to corporate overreach and female consent – it doesn’t

connect meaningfully with anything else: the data collected from Oshii’s film

is pinged round inside the new film’s circuitry without it ever threatening to

accumulate any critical mass. The result is a Ghost for the Twitterati, all flashing lights and pretty colours,

at once distracting and distractible, busily spinning its wheels ahead of a

citytrashing finale that recalls… well, every other citytrashing finale of the

past half-decade.

As with Twitter, the film is not without its passing,

superficial pleasures, and non-devotees might soak up some of its stimuli for

future repurposing as profile photos, or as the backdrop to a club night. Sanders

is becoming increasingly adept at framing the kind of images any 14-year-old

would deem cool (Scar-Jo in slo-mo, erupting through plate glass in latex!),

which should ensure smooth progress in the modern movie business. Yet whatever

philosophical nuggets were lurking amid Oshii’s tangled plotting, they surely

merited closer consideration by a filmmaker who wasn’t just trading in gloss,

and doesn’t merely regard human beings as elements of design.

Grade: B-

No comments:

Post a Comment