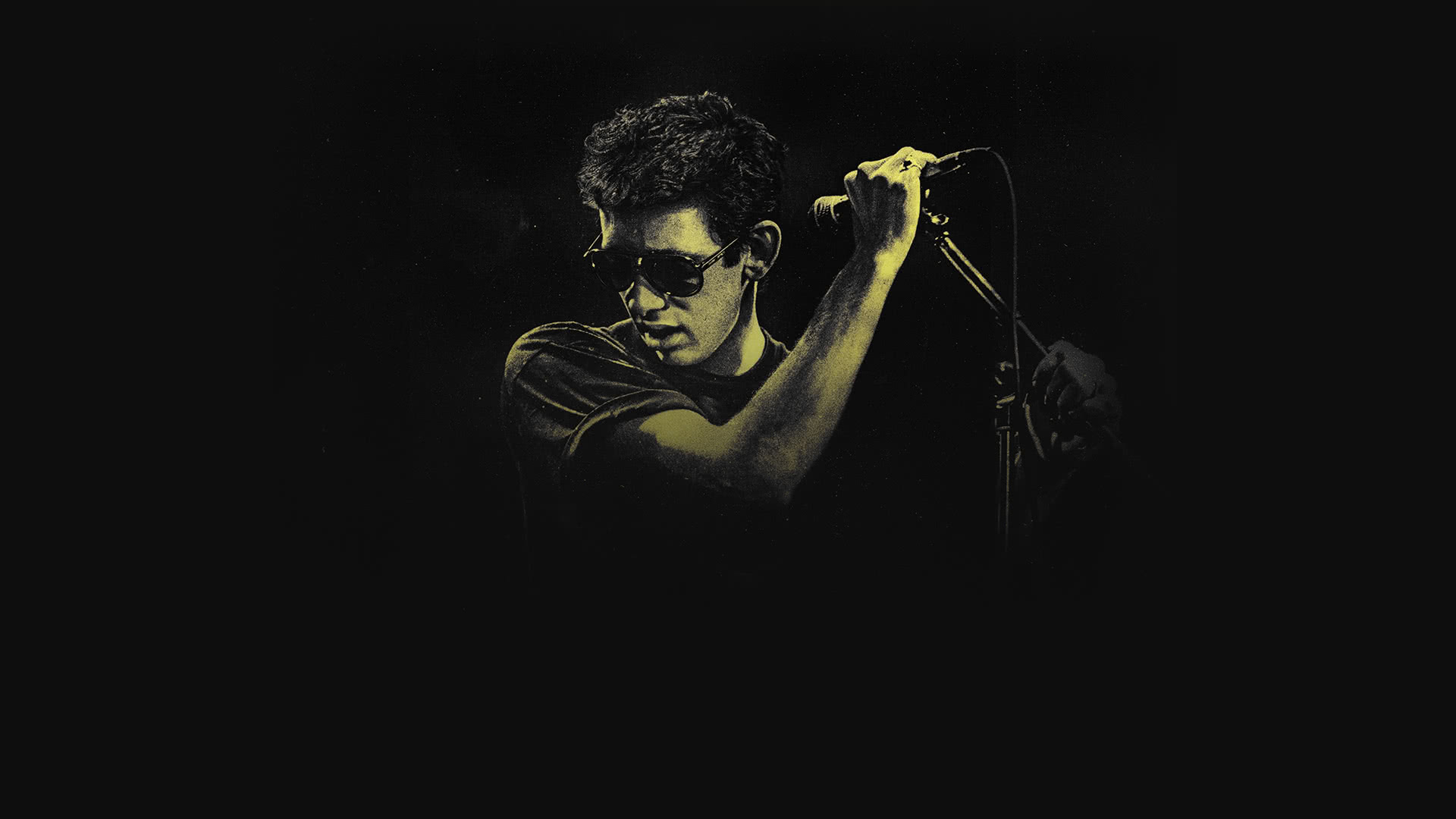

In some respects, Crock of Gold represents a near-perfect match-up between documentary filmmaker and subject: it's Julien Temple applying his trademark punkily irreverent mix-and-match aesthetic to the sandpaper-rough legend of Shane MacGowan, lead singer with The Pogues. MacGowan is joined, pre-pandemic, in his sixties, in a wheelchair and with a gleaming new set of teeth, but otherwise still drinking, smoking and meeting the world head-on with that disarming Muttley laugh; he's introduced, however, in cartoon form - very Temple, this - as an altogether fresher-faced young lad, charged with exporting traditional Irish music and Irish culture to that world. The narrative line the film pursues from there, inevitably wayward and wobblier, offers plenty of reasons why young MacGowan might have taken to the drink so: being born into the poverty of what was still effectively a British colony, left to kick up skulls while playing on the beach, and confronted every Sunday with the blandness of a Catholic heaven, if you weren't already condemned to Catholic hell. (The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was in making the pub a livelier venue than church.) It hardly seemed to get much easier when MacGowan left Ireland behind and travelled to London in the 1970s - hardly a promised land, rather a place where the old "No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs" mentality held sway, enough to leave any recent arrival weighing up the escapist merits of glue sniffing. According to Temple's account, it was the music that best sustained MacGowan through this period: here was a reminder of the singer's roots, and a means of snarling in the face of all that was or was becoming politely conservative. This, however, feels instinctively like an overly rational reading of the most haphazard and devil-may-care of pop lives.

For better and worse, the film is scarcely less haphazard in its methods. Even before the appearance of yer actual Gerry Adams in the MacGowan front room, Crock of Gold makes for eccentric viewing. The version screened to press opened with the title card "Johnny Depp presents" - which seems a curious framing in late 2020 - and Depp recurs in person on screen, engaging a not untypically prickly MacGowan in a dead-end Q&A during a light lunchtime drinking session. "What makes you think I stayed awake during Pirates?," MacGowan gurgles at his pie-eyed interrogator. "What makes you think I did?," comes the Depp response. I began to wonder whether Temple isn't guilty of being overly romantic around piss artists - those creatives who've come to pour at least some of their talent down the drain - seeing something honourable in their stubborn refusal to return to their digs after kicking-out time to do what we expect creative people to do with their gifts. If I'm not mistaken, Depp also helps out with the voiceover, drafted in to impersonate the singer in spots, because Temple's boldest choice was to try and tell the Shane MacGowan story in MacGowan's own words. The trouble with that is that authenticity sometimes comes at the expense of basic audibility; the film's a BBC Films production, and I suspect the service formerly known as Ceefax 888 will experience high demand when it's broadcast in the weeks ahead. Even when its subject is relatively sober and correctly miked, the device of having MacGowan prodded by celebrity interviewers generally comes to naught. "Stop interrogating me," MacGowan snarls at Bobby Gillespie. "Can't we get off the subject?" (And we realise: some people turn to drink specifically to get off the subject.)

What keeps these two hours broadly on course is the Temple technique, as playful and evocative as ever; we sense he could tell this story around his subject, if the latter got too abusive or incoherent or simply nodded off. Temple absolutely understands the punk scene MacGowan fell into upon his arrival in London: he doesn't just source the most evocative Super-8 footage of the old Piccadilly Circus, where MacGowan reportedly served as a rent boy to make ends meet, but he knows the right faces to search for within that, the better to punch up the idea of a violent contrast, that something was happening that was to shake up twee Albion, however briefly. Temple even finds a new angle on that tattered music-doc trope Rockers Recall Having Minds Blown By Early Sex Pistols Gig: MacGowan apparently rocked up to one of those after checking out of a mental hospital. The other strength here is the music - something old, given a renewed Dolby oomph. Crock of Gold wisely gets that festive pop albatross "Fairytale of New York" out of the way early on, sensing it's already been discussed to something close to death; it knows there's far more to this back catalogue, annual entrypoint though that song may have become. My feeling remains that the story of MacGowan's progress from Ireland to the UK mainland is more compelling than what followed; as we stumble out of the Eighties and into the Nineties, Crock of Gold lapses into repetition. It's the circular drama of how to keep an alcoholic functioning, of people attempting to control MacGowan's drinking long enough for him to write new material and give the hardest working liver in showbiz a break. Points off, too, for the inevitability of Bono, found belting out an earnest tribute at the singer's 60th birthday concert. Still, it would be misguided to expect sustained clarity and coherence from any film about Shane MacGowan - and if preeningly nurturing your talent results in Bono, then perhaps we'd all do well to develop a taste for the harder stuff.

Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan opens in selected cinemas from Friday, ahead of its DVD release through Altitude next Monday.