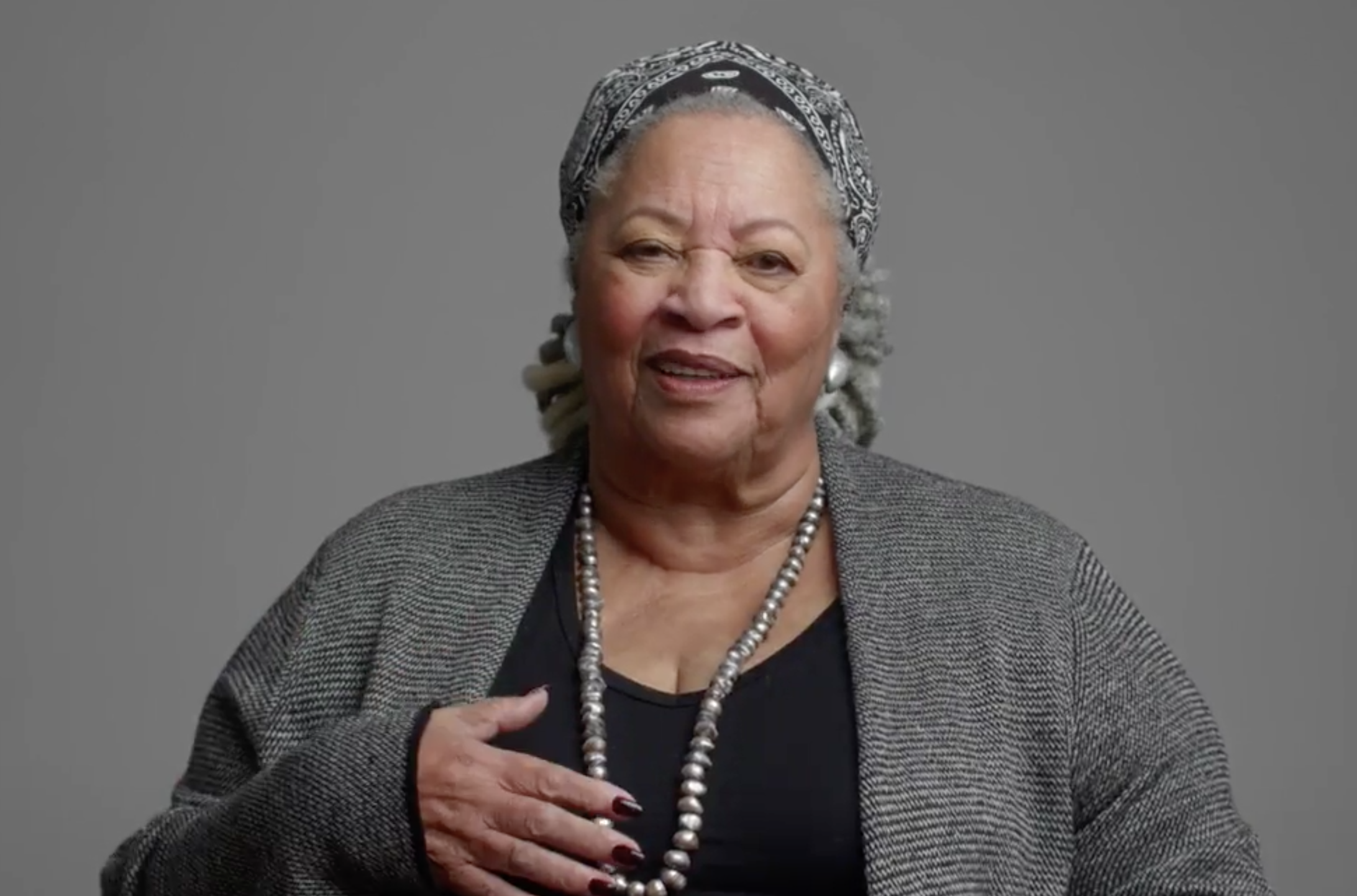

Full disclosure: I arrived at this documentary on Toni Morrison as a near-complete blank slate, someone who was aware of the American author's standing as a towering figure of 20th century literature, but who'd somehow never sat down with one of Morrison's books. (Exposure to Jonathan Demme's well-intentioned but horribly laboured 1998 adaptation of Beloved at a culturally formative age may have been a factor.) Happy to report, then, that Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am is about as complete a primer as a neophyte might want, and likely a useful resource for long-time admirers, too, founded as it is on one of the last indepth interviews Morrison gave before her death last August from pneumonia. So here is Morrison - grey-haired and matronly, warm and wise, alive once more - talking straight down the camera, with a directness of address seasoned readers may recognise, about her background, methods, individual texts, the battles she's fought on the page and in person, and how a young woman born Chloe Wofford in Lorain, Ohio became a Nobel Prize recipient and one of the most admired and respected names in the canon. This is also, we very quickly understand, the story of how American society reorganised itself, in the course of the 20th century's second half, to make room for a voice such as hers.

That story is set out by the director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders in the unhurried, unflashy house style of PBS's American Masters series, the strand that previously brought profiles of Woody Allen and the Eameses to our screens: a reassuringly familiar mix of first-person testimony, evocative archive footage, unobtrusive, jazz-inflected music cues, and select talking heads (in this case professors, publishers and fellow writers Walter Mosley and Russell Banks). The film's substantial backbone is that relaxed, wide-ranging interview (conducted by Sandra Guzmán), in which Morrison proves as comfortable discussing the iniquities of the publishing industry and her efforts to dodge the white gaze that has held such sway in literature circles as she is the wildness of her college days, or the shortfalls of her sister's carrot cake ("They don't put enough carrot in!"). This, in turn, affords the researchers time to rummage around for choice archival titbits. A methodology is established by the opening montage, collaging portraits of Morrison at different ages; a lovely grace note is sounded when Greenfield-Sanders illustrates Morrison's big mid-Sixties move from Lorain to New York (where she was to work in the editorial department of Random House) with a clip of Sister Rosetta Tharpe - like Morrison, another distinctive African-American voice who came to prominence in later life, trailing a weight of experience. (Doubtless Morrison learnt much from editing other people for a living - and Angela Davis is on hand to testify as to how Morrison's editorial nudges helped make her autobiography, written when she was just 28, so evocative.)

We might detect a certain reluctance to delve too deeply into Morrison's personal life, that this picture still has a few pieces missing. We hear in the opening minutes that Morrison used to wake in the wee small hours to write before her young children got up, but learn nothing at all about the father, nor where he disappeared to. (The film is notably more comfortable addressing the fictional parent-child relationships of Beloved.) Even here, though, telling biographical detail slips through: a friend informs us Morrison made a rule to keep her door open when writing, so her offspring didn't feel as though they were being distanced. (This, I suspect, will make any onlooking writers feel supremely guilty about their parenting and productivity levels.) The tone throughout is celebratory, keeping Morrison front and centre as a hardy survivor, but the research and testimony keeps alighting upon the complications of late 20th century black life: you sense a flicker of unease as the rostrum camera scans a review of the Morrison-compiled 1974 almanac The Black Book and notes the introduction was written by Bill Cosby, while one interviewee introduces the provocative wrinkle that Morrison's work initially sold more copies overseas than it did in the US. Was it too close to home, as the ongoing attempts to ban 1970's The Bluest Eye from schools signal? That The Pieces I Am troubles to raise such questions is a testament to the thoughtfulness of its content; if it remains a little televisual in form - foursquare in its look, sober and PBS-scholarly in its analysis, more Ken Burns than Errol Morris - it'll only benefit from the present state of lockdown. Watching the film on your laptop makes it easier to pause, open up a browser, and order yourself the back catalogue.

Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am is now available to rent via Amazon Prime.