Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda's rapped musical account of the role the Nevis-born bureaucrat Alexander Hamilton played in the founding of the United States, became such a sensation so quickly that someone was always going to think of further monetising it by converting it into cinema of a form. Given that tickets for both its Broadway and West End runs were trading hands at upwards of £70 a pop, when they were available at all, that conversion could at least be justified as a field-levelling public service. So here it is, coming down the tubes care of Disney+: a film of arguably the 21st century's most unlikely cultural phenomenon, as recorded on the stage of Broadway's Richard Rodgers Theater back in 2016. (Presumably the recording has been held back four years to allow the stage production to carry on coining it in - though it also allowed Disney to test the waters with their refilmed version of Newsies, the flop-movie-turned-hit-musical about turn-of-the-20th-century paperboys discovering their inner Marxist. Say what you like about this corporation - and I have - but liquidity has allowed them to entertain some properly loopy ideas.)

Out there in the multiverse, there's a version of Hamilton that was no more than the minor fringe talking point its logline promises - a version that didn't have money in the bank to beef up the beats on its soundtrack, which never appeared on the Disney radar. Watching the film of the show, one realises the extent to which that show was always a tightrope walk: it relied on its performers being word- and note-perfect, because any slip or stumble, any failure to put the lines over with the required force, risks exposing what a truly batshit idea this was from the outset. The film thus arrives as proof that they pulled it off - that a bunch of pros landed on a crazy notion, workshopped it, rehearsed their behinds off, kept their fingers crossed people would turn out for it, watched as this goofball wheeze became a modern theatrical landmark, and eventually signed the deals that presumably made them millions. It's the American Dream, just not as Alexander Hamilton himself would have recognised it.

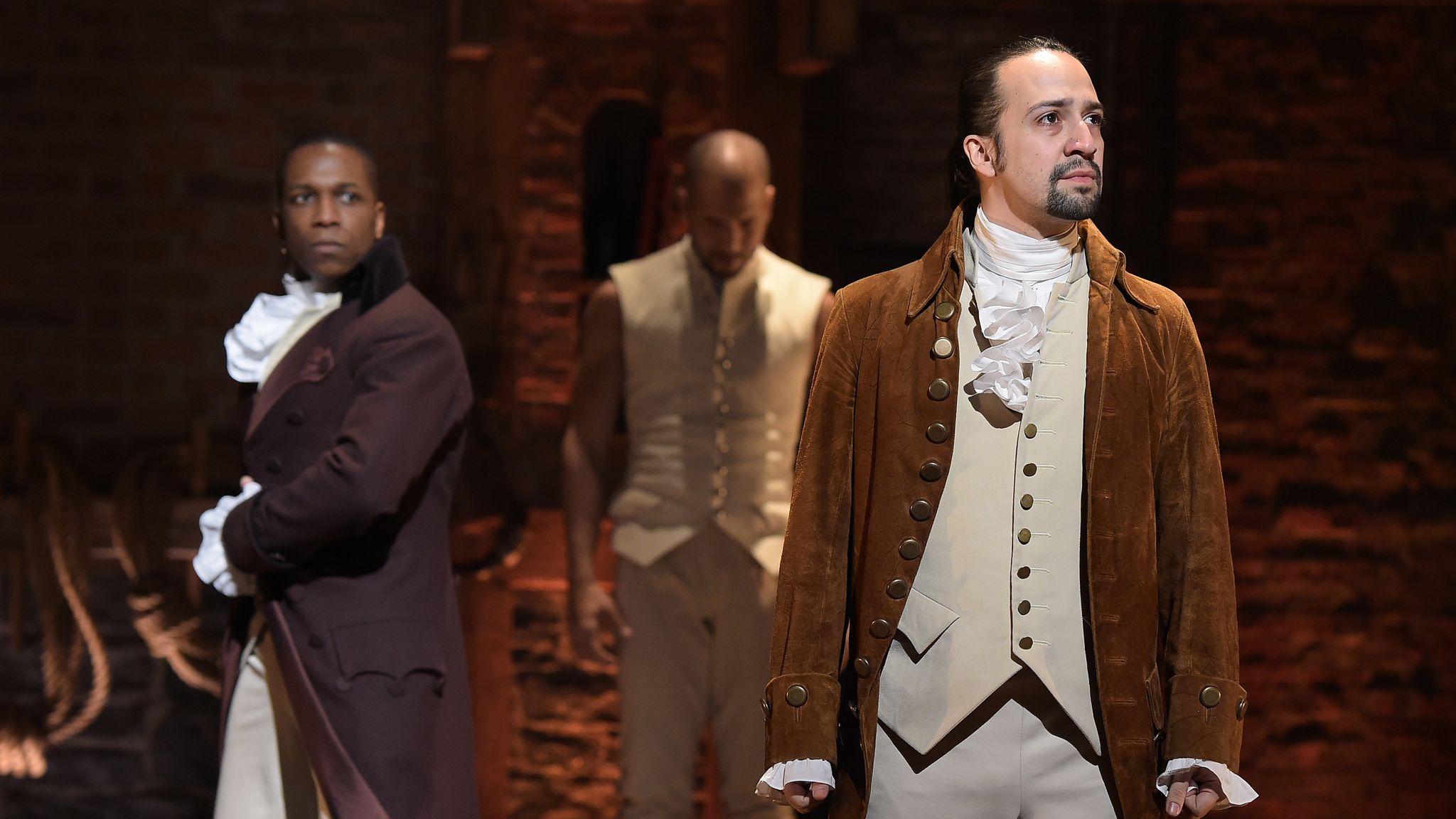

It was a crazy idea, executed with tremendous skill, great craft and not inconsiderable chutzpah. Much of its success can be ascribed to Miranda's gift as a songwriter: his ear for melodies that stick, his fondness for lyrics that pop and crackle, his knowledge of how the Great American Songbook has expanded here and there over the past twenty years. Hamilton seizes upon whatever wiggle room was left in those pages at the end of the twentieth century, and proceeds to make a big song-and-dance in it. So we get swaggering, crotch-centric proto-revolutionary rap for Hamilton (played by Miranda himself) and his cohorts, but also pastichey pop for an eye-rolling King George (Jonathan Groff, graduate of Glee's McKinley High); slinky, En Vogue-style R&B and Nicki Minaj-like thirst tunes for the Schuyler sisters (Renée Elise Goldsberry, Jasmine Cephas Jones and Phillipa Soo), with whom Hamilton becomes romantically and platonically entangled; and every now and again, the kind of self-empowerment anthem ("Wait for It") which was always bound to catch Mouse-shaped ears. A lot of syllables get squeezed into these two-and-a-half hours, cumulatively adding to the thrilling implausibility of the spectacle, and suggesting another influence besides.

Miranda would have been 20 when Eminem's The Marshall Mathers LP came out at the start of the century, and given some of Hamilton's phrasing and rhymes, it would surprise me if that wasn't somehow a seismic event in this creative's life. Yet Miranda (and thus Hamilton) is what happens if your Marshall Mathers is a peppy, can-do drama and history student, rather than a brooding trailer-park malcontent. That altogether brighter outlook surely accounts for the play's conception of Hamilton as a scrappy, penniless underdog rising up to razz the establishment, albeit in such a way that doesn't leave that establishment too far out of joint or pocket. Two of the many things one learns here about Alexander Hamilton is that he went on to set up Wall Street and the New York Post: he was as much conservative as romantic rebel, much as - for all its sick beats - Hamilton is still a history play that ends with a duel. I think that explains the vast crossover success: this was never some angry, avant-garde exercise in historical revisionism, rather a fun night out for young and old alike.

The challenge any film of that night out faces is to capture that fun and transmit it further still. Hamilton is stuck on the show's (granted, multifaceted) set: it admits as much by including the pre-show message imploring patrons to switch off their phones, and a minute-long intermission between its two acts. Director Thomas Kail (who oversaw a live TV version of Grease in 2016, and went on to direct FX's Fosse/Verdon miniseries) and his experienced cinematographer Declan Quinn (Vanya on 42nd Street, Leaving Las Vegas) are themselves engaged in a highwire act. They have to pick the exact right shots to sustain and convey the production's own internal momentum: the cast skipping on and off, those syllables being sprayed in every which direction, the set rotating at intervals. They were wise to keep the camera back in the main, possibly out of a desire not to get in the way of all that; we sense the reluctance to trip either the play, the performers or the phenomenon, but that judicious editorial policy also allows us simply to marvel at a hell of a show going on.

There are points in that show where we notice the energy starting to flag a little. The Washington infighting of the second half is less transporting than the revolutionary fervour whipped up in the first, but even that serves the book's more reflective material. Somewhere in here, Miranda was reckoning with youthful ideals (in both individuals and nations), and how they get tempered, sometimes worn away by lived experience. What makes Hamilton more than just a novelty hit is that there is wisdom here to mull over on your walk back to the subway (or kitchen). The film's most immediate achievement, however, is to explain this phenomenon to the layperson: why Hamilton exists, why it became the smash it did. Viewed in this year of course correction, this looks very much like the kind of caprice that could only have sneaked past our gatekeepers in the relative leeway of the Obama years; having landed that break, Hamilton became as much of an escape for besieged liberals enduring the Trump administration as The West Wing (whiter, but similarly logorrheic) was during the Bush regime. As a project, Hamilton appears as democratic as America likes to think of itself, pushing the idea that any little guy - an Alexander Hamilton or a Lin-Manuel Miranda - might suddenly find themselves at the centre of a very large stage, with the world at their feet. "Immigrants, we get the job done," this Hamilton joshes with French associate Lafayette (Daveed Diggs) early on. Did they ever, in this case.

Hamilton is now streaming via Disney+.

No comments:

Post a Comment