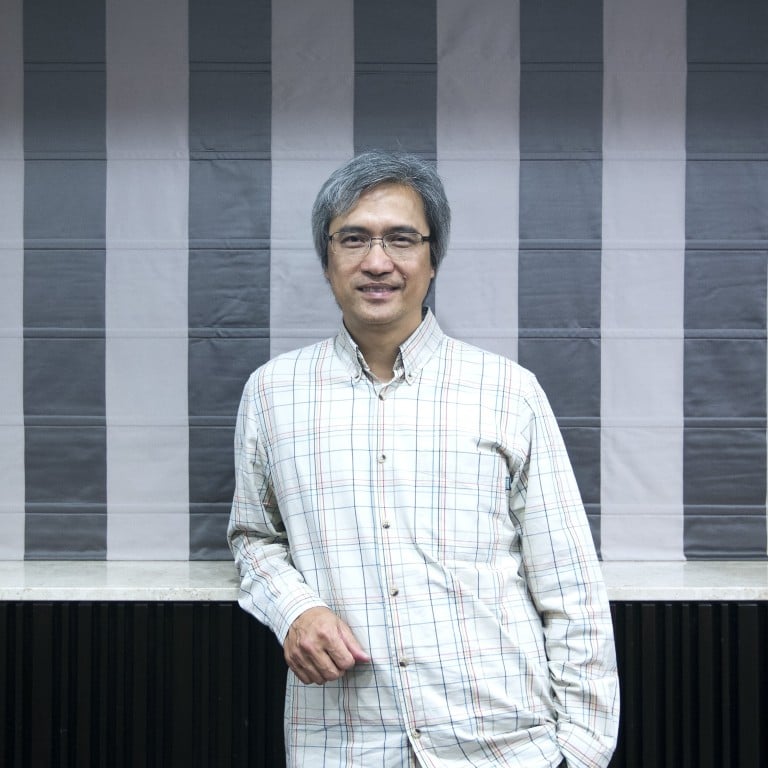

Benny Chan, who has died

aged 58, was among the most prominent directors to have emerged in recent years

from the Hong Kong film industry’s genre sector, overseeing a run of

high-octane action pictures that thrilled local audiences before tearing onto

Western cinema screens.

His career was fashioned

in the image of his restless mentor Johnnie To, for whom Chan worked as an

assistant in HK television in the late 1980s. As To has, Chan worked skilful

variations on the theme of law-and-order, habitually returning to the sight of good

guys squaring off against bad, although he occasionally branched out into more

unusual territory, with mixed results.

In interviews, he spoke often

about his desire to develop beyond genre fare, but lamented that this ambition

was continually thwarted by producers thrusting another policier script upon

him: “When they come to Benny Chan,” he mused, “it must be about action.”

Nevertheless, in his better projects, the bespectacled, mild-mannered Chan

succeeded in imbuing his onscreen carnage with poetry and wit.

Born Chan Muk-sing in

Kowloon on October 7, 1961, he became a cinephile as a teenager, attending

matinees of the Shaw Brothers’ kung fu productions. Upon graduating in 1981,

Chan found work as a clerical assistant at local broadcaster Rediffusion TV,

but confessed he spent less time in the office than he did skulking around the

station’s studios and pestering the directors.

He got his shot upon

defecting to rival, Shaw-owned TVB a few years later, where he directed 37 and

wrote all 40 episodes of the action serial The Flying Fox of Snowy Mountain

(1985). After serving as an assistant on Raymond Wong’s cancer-themed comedy Goodbye

Darling (1987), he made his feature debut with A Moment of Romance

(1990), a star-crossed lovers melodrama starring local pin-up Andy Lau as a gangster

who falls for an heiress (Chien-Lien Wu).

Balancing sweeping action

with swooning drama, the film was a hit, and another sign of renewed confidence

within the HK industry: it opened in the period between John Woo’s early

successes The Killer (1989) and Bullet in the Head (1990), and

just months before Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild (1990).

Yet it was working

alongside his namesake Jackie Chan – then in the process of cracking the

American market – that the director achieved his biggest success, finding dynamic

ways to showcase the star’s trademark “chopsocky” (a lighter, more comic form

of kung fu, blending martial-arts with slapstick).

Who Am I? (1998) had a stock spy-movie plot – Chan’s amnesiac

agent is pursued by shadowy forces – but it was energised and elevated by the

director’s inventive staging: one sequence in Rotterdam saw the star repelling

his pursuers while clad in traditional Dutch clogs. Recut by distributors for

international release, the film performed well in Western multiplexes, doubly

so on home video.

They would reteam for New

Police Story (2004), named to remind the star’s fans of his wildly

successful 1980s series, but otherwise a very different proposition: here, the

now-fiftysomething Chan played the world-weary Inspector Wing, and attempted to

flex his dramatic muscles. This rebrand barely took: local audiences preferred

the Chans’ earlier, funnier work, and the film limped onto British screens two

years later to mixed reviews. (The Observer’s Philip French damned it as

“an addled affair”.)

Unhappier still was the

pair’s reunion on Rob-B-Hood (2006), a leaden comic caper about a pair

of thieves who find themselves minding a baby. The director confessed that

adding an infant to his star’s complex (and often injurious) stunt sequences

led to several of his darkest days; the film went straight-to-DVD in the

States, and undistributed in Britain.

Chan returned to form

with Connected (2008), a remake of the so-so Hollywood thriller Cellular

(2004) in which an everyman hero (future Captain America Chris Evans in the

original, director favourite Louis Koo here) takes a stray call from a

kidnapped woman and becomes implicated in her fate. Chan added not just a

climactic forklift truck rampage but believable characters to Larry Cohen’s

original story: in his version, the debt-collector hero is overburdened even

before he’s obliged to screech around town in a succession of amusingly

midrange cars.

A goofy fantasy about

circus performers given superpowers after coming into contact with a biohazard

abandoned by the Japanese during WW2, City Under Siege (2010) received

lacklustre reviews, and failed to make back its not inconsiderable budget. Shaolin

(2011), a remake of Jet Li’s 1982 debut, similarly struggled to recoup its

producers’ investment, in part due to its full-scale reconstruction of a 1920s

temple.

Yet the director returned

to surer ground with The White Storm (2014), his self-described John Woo

homage, loosely inspired by the Pablo Escobar story. And he won glowing reviews

for Call of Heroes (2016), a period actioner choreographed by Sammo Hung:

Variety described it as “a glorious throwback to the rustic vigour of

[the] Shaw Brothers”.

His weirdest credit followed

with Meow (2017), a would-be summer blockbuster involving an outsized

computer-generated feline. This calculated play for a family audience drew

indifferent reviews (“the action veteran would be smart to stick to his day

job”, advised the South China Morning Post); it opened on a single

British screen, taking a mere £118 on its opening weekend.

During shooting last year

on Raging Fire, a return to the crime genre starring Donnie Yen, Chan

was diagnosed with nasopharyngeal cancer, and handed the film over to

colleagues for post-production before undergoing treatment. (The film is

scheduled for release later in 2020.)

Asked about filmmaking in

2014, Chan said: “I always feel very complicated when thinking about it. I feel

everything – happiness, anger, sorrow, and happiness again – but I’ve never

considered it a job. Maybe that’s why I’ve survived so many things... I hope

that I can find my own world in the movies and pass that happiness onto the

audience, just like the happiness I took from films when I was a child.”

He is survived by a wife,

a son and a daughter.

Benny Chan, born October 7, 1961, died August 23, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment