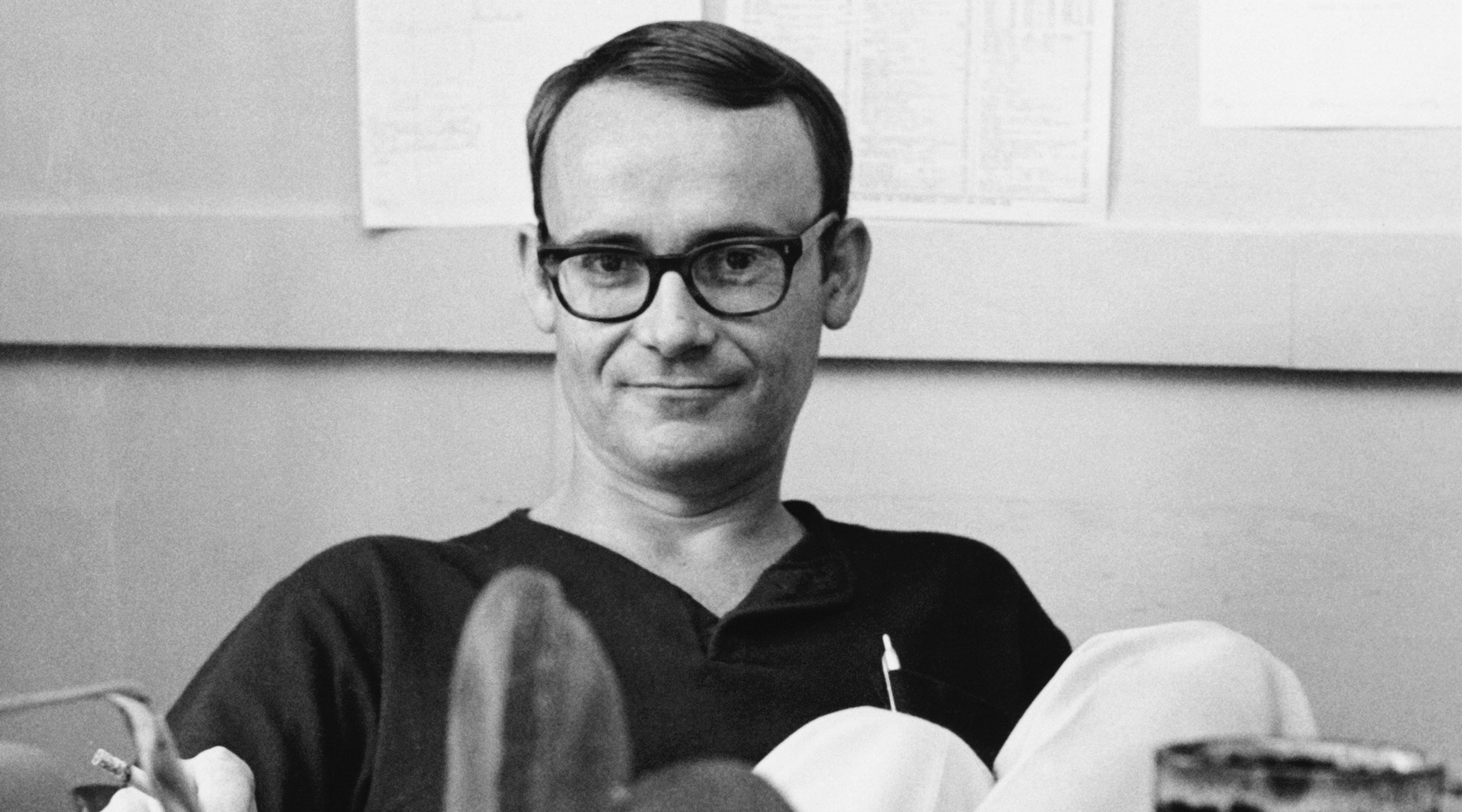

Buck Henry, who has died

aged 89, was an idiosyncratic performer, screenwriter and director who burst

out of the American counterculture to generate many of screen comedy’s most

memorable characters, scenes and lines.

His break came working alongside

Mel Brooks on TV’s long-running spy spoof Get Smart (1965-70), but it

was Henry’s work on The Graduate (1967) that would position him close to

the heart of the iconoclastic New Hollywood.

Henry was the fourth

writer hired to adapt Charles Webb’s source novel, but the first to fully synch

with director Mike Nichols’ leftfield sensibility. It was Henry who added the oft-quoted

discussion between dreamy Ben Braddock and a pompous family friend (“Just one

word… plastics”); he also engineered the subversive, bittersweet ending,

delaying Ben’s arrival at the church until after Elaine

had pledged her troth to another man. (In Webb’s book, he arrives just in

time.)

Henry and co-writer

Calder Willingham won the Best Screenplay BAFTA; the pair also gained an Oscar

nomination, but lost out to In the Heat of the Night. Nevertheless, Henry’s

close association with an era-defining film (he even wrote himself a funny

cameo as the owlish hotel clerk making Dustin Hoffman squirm) launched him to

newfound prominence as both a writer and performer.

In the former capacity, he

made a slightly underrated stab of adapting Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1970),

again for Nichols; handed Barbra Streisand and old friend George Segal snappy

lines for The Owl and the Pussycat (1970); and contributed the polish

that gave Peter Bogdanovich’s Streisand-starring screwball homage What’s Up,

Doc? (1972) its enduring sparkle.

As a performer, he was

the prematurely middle-aged hero of Milos Forman’s sleeper hit Taking Off

(1971), conspired with David Bowie as the patent attorney Farnsworth in The

Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), and nurtured an enthusiastic younger

following by hosting the new Saturday Night Live ten times in its first

five years.

He rounded off the decade

as a writer-director, care of a fraught (albeit Oscar-nominated) collaboration

with Warren Beatty on the fantasy Heaven Can Wait (1978). Yet by the

time of his second and last directorial credit, First Family (1980), it

was clear that some creative freedoms were slowly being revoked. The success of

the ultra-merchandisable Star Wars meant Hollywood was pivoting away

from irreverence and towards a vastly more profitable market: plastics.

He was born Henry

Zuckerman on December 9, 1930 to former silent screen actress Ruth Taylor and

Paul Zuckerman, an Air Force general turned Wall Street stockbroker. A creative

child, Henry joined the ensemble of Broadway’s Life with Father at

sixteen, before touring Germany with the Seventh Army Repertory Company. At Dartmouth,

where he studied English literature, he cut an eccentric figure, wearing his

pyjamas at all times.

Upon graduation, Henry

won a measure of notoriety as a hoaxer, appearing on several TV shows in the

guise of G. Clifford Prout, president of the Society for Indecency in Naked

Animals, insisting that all large animals should be clothed and trumpeting the slogan

“A nude horse is a rude horse”. Surprisingly, he was taken at face value by

several media figures (including Walter Cronkite, who never forgave Henry) and

some viewers, who began sending in donations to the SINA cause.

In 1960, just before his

decisive move to L.A., Henry set up the off-Broadway improv group The Premise:

“If you’re up onstage every night for a year… with the audience yelling

suggestions at you like ‘Do Chekhov, but do it with Chinese characters’, you

get used to an immediate commitment to lunatic ideas.”

Once the sun set on New

Hollywood, he enjoyed a renaissance as a character actor in such cultish titles

as Eating Raoul (1982) and Albert Brooks’ Defending Your Life

(1991). He appeared as himself in Robert Altman’s Hollywood satire The

Player (1992), pitching a Graduate sequel in which Ben and Elaine

are forced to cohabit with an ailing Mrs. Robinson, and later reported that an

actual studio executive had approached him with an eye to developing the idea.

He wrote the smart black

comedy To Die For (1995), and appeared on TV’s 30 Rock (2007-10)

as Liz Lemon’s wide-eyed father Dick, before being recruited by news spoof The

Daily Show (2007) to serve as their “Senior Historical Perspectivist” in a

segment titled “The Henry Stops Here”. Asked to justify the title, he insisted

“It’s because my name is Henry, and I’m stopping right here”.

He is survived by his

wife Irene Ramp, and by an unnamed daughter from an earlier relationship.

Buck Henry, born December 9, 1930, died January 8, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment